Alex Dolores Salerno: "Arranged With Care"

- Bert Stabler

- Oct 17, 2022

- 11 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2023

Alex Dolores Salerno, Arranged with Care, 2022. 2 channel video, airplane pillowcase, herbs, and the color of horchata lojana. Dimensions variable. Installation photo by Sebastian Bach, courtesy of Ford Foundation Gallery

Alex Dolores Salerno, Arranged with Care, 2022. 2 channel video, airplane pillowcase, herbs, and the color of horchata lojana. Dimensions variable. Still from the video with Spanish audio.

Alex Dolores Salerno, Arranged with Care, 2022. 2 channel video, airplane pillowcase, herbs, and the color of horchata lojana. Dimensions variable. Still from the video with English audio.

Alex Dolores Salerno describes themself on their website as “an interdisciplinary artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Informed by queer-crip experience, they work to critique standards of productivity, notions of normative embodiment, 24/7 society, and the commodification of rest.” In their work, they largely make use of artifacts, materials, and ideas taken directly from their lived experience, in which rest, care, and reflection are central and necessary elements. Their aesthetic is defined by an intimate scale, forms that embody gravity, and the subdued colors and smooth textures of well-worn items.

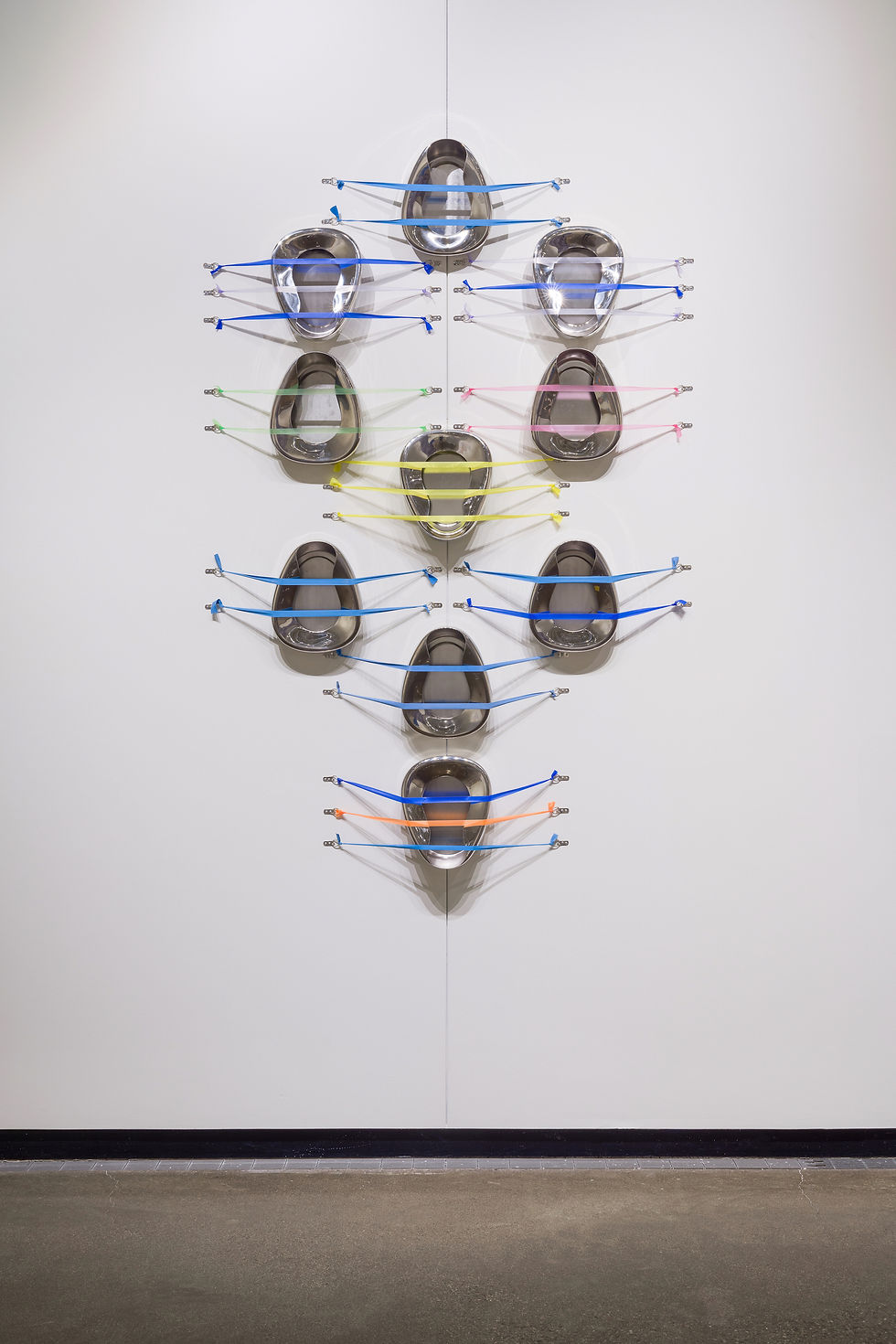

Alex has three pieces now on display at the Ford Foundation Gallery in New York, as part of Indisposable: Tactics for Care and Mourning, a major group exhibition focused on contemporary disabled artists. In their reflections below, Alex shares some of their process and intention for their newest piece in the exhibition, pictured and linked above, entitled Arranged with Care. The show also features their sculptures Regalos and EXTRAHERE, both works that index time through a patient process of threading delicate organic items in a consistent serial process.

--Bert Stabler

Below Alex describes the exhibition, focusing on their installation Arranged With Care.

Arranged with Care is a video installation commissioned by the Ford Foundation Gallery for the exhibition Indisposable: Tactics for Care and Mourning curated by Jessica A. Cooley and Ann M. Fox. This in-person exhibition is an expansion and culmination of the exhibition Indisposable: Structures of Support After the ADA which shifted from an in-person exhibition at the Ford Foundation Gallery to a virtual exhibition, which ran from September 2020 to February 2022 with a series of events called “chapters” debuting new commissioned works by disabled artists featuring dialogues with the artists and their friends and collaborators. I was commissioned to make my first video piece for the first chapter of Indisposable in 2020. The title of the video, El Dios Acostado, translates to “the sleeping god” which is a translation of “Mandango” which is the name of a mountain in southern Ecuador near my mother’s hometown. The video begins with my partner and collaborator Francisco echo Eraso lying in a field of grass facing the mountain and taking a nap alongside it. The shape of Mandango is said to look like a sleeping god guarding over the small town of Vilcabamba which has been known as “the valley of longevity” due to research published in Western sources from the 70s such as National Geographic on the high concentration of people over the age of 100 in the area. This publicity attracted tourists seeking adventure and gentrifying the town. In the video my mother explains this history while also describing her love for her hometown. While the video does not directly mention disability, it is highly informed by disability culture and aesthetics in its embrace or rest and interdependence with the land and community. It also is set to a pace of rest through a doubling of the narration. Each scene begins with a visual description followed by my mother speaking, with everything spoken twice, once in English and once in Spanish, with 2 sets of captions in the center of the screen in both languages.

Since making El Dios Acostado I had been eager to continue exploring the materiality of access in video and also to collaborate with my mother again. We decided that we would do a video about or involving horchata, which is also called horchata lojana. Lojana refers to Loja where my family lives in southern Ecuador. This traditional drink is very different from the rice based Mexican horchata that many north Americans are familiar with although it has the same name and has similar origins as horchata began in 2400 B.C. Egypt with the tuber “chufa”. Horchata is a drink that has changed based on what’s available depending on location and local tastes. In southern Ecuador it’s a pinkish red medicinal drink made with a large variety of herbs but there are at least a dozen or more that are most frequently used (such as amaranth, bloodleaf, chamomile, mint, lemongrass, lemon verbena, lemon balm, borage, mallow, basil, etc.).

In the fall of 2021 my mother traveled to Loja to visit family while I stayed in NYC to avoid traveling from a high Covid risk area. We hadn’t discussed what a future video might look like so it was a surprise when she texted me a video shot on her iPhone with the help of my aunt. She told me that the video was just a test but the spontaneity of it felt so wonderfully tender that I decided this had to be it.

In my previous video, El Dios Acostado, each scene was shot as a silent timelapse so I was able to add narration in both English and Spanish easily in the same video. For Arranged with Care, which was originally shot in Spanish, I couldn’t interpret the video into English in the same way since my mother was moving and speaking very fast. I thought about having the video only exist in Spanish with the understanding that the idea of something being “fully accessible” is not necessarily a reality. But I really wanted to further explore translation/interpretation as access, and have that access to both languages available in the same space, as well as using captions as a key aspect of the visual rather than a subtitle or afterthought. Something that struck me when learning about access practices for zoom events in the past couple years is that when there is live Spanish interpretation during an event, the participant typically has to click a link that takes them out of the zoom event. In my video work I want to see what can happen when everything is there. Something I found is that this excess, which is really not excess at all but might appear as such, can create a slower viewing experience. Arranged with Care turned into two videos, one in Spanish and the other interpreted into English. The two videos are displayed side by side on separate monitors in the gallery.

A piece of advice I received that informed this work was better access isn’t necessarily something that is replicated one-to-one but rather provides a better experience. When thinking of translating the original Spanish video to English, and recording the translated script I realized that I could never recreate the moment between my mother and my aunt in a recording studio, especially without my aunt present. In the original my aunt humorously reminds my mother of the names of each herb everytime my mother tries to introduce them to the viewer. My mother and I visited a recording studio not really sure what we would do, and we quickly found it really hard to try to force a natural sounding conversation. I realized there that the best way I could recreate a back and forth between us for the English version of the video would be to have my mother speak in English but say each herb in Spanish, and I would follow with the English name of those herbs. This result reflects the process of creating the video work as a whole, through translating the Spanish video into English and then translating the new English version into Spanish, I am also learning Spanish with my mother as I wasn’t taught the language as a child because this country does not value it and my mother was forced to assimilate.

With the video doubled, I’m able to have visual description and captioning in both languages simultaneously in the same space. Each version of the video has 2 sets of captions on the screen in English and Spanish. The language being spoken is in white text and the translation is in yellow underneath. Because there is a lot happening on screen there is a transparent yet dark background behind the text to create contrast. The text is large in the center of the video and in an open source font called Open Dyslexic. In the gallery the video is heard through headphones, one pair for each monitor / language, and there is a viewing bench in front of the two monitors. I decided to intervene in the form of the standard gallery bench by painting it in the color of horchata Lojana. Horchata is a vibrant ruby red color, although it can also be fuschia depending on how it's made and if you add lime juice. I learned about the importance of the color when reading a research study on horchata. To quote them, "In the ancestral memory of indigenous populations, especially those located in the Southern Andean highlands of the country; the intense color of 'horchata' is associated with physical and spiritual strength. Through this perception, people that consume this drink feel invigorated." I’m interested in the healing power of color, particularly in a white cube or institutional context. On the painted bench will be 3 felt pads in a similar color to sit on and the middle pad will hold a touch object. Several of my past works involve pillowcases so I’ve been holding onto a pillowcase from an airplane pillow that I took from the last time I was on a long flight. I stuffed the 12 by 14 inch airplane pillowcase with a few pounds of dried herbs used in horchata. Feeling the weight and crunchy texture of the stuffed pillowcase felt both comforting and satisfying and reminded me of other weighted stim toys that I’ve experienced. It also has a very interesting scent that is difficult to describe since it’s a mix of several herbs. Some of the most prominent scents are minty, lemony, and earthy. It’s important to me that I consider folks with sensitivities to scent so I did not use anything chemical, artificial or overpowering scent. Finally, to indicate that it can be touched I embroidered “hold me” and “puedes tocarme” onto the pillowcase. I decided on using a pillow as a way to embrace the herbs introduced in the video rather than display them for a few reasons. The first is that the airplane pillow reflects how the video was made across countries in a time when travel is tricky due to Covid. It also allows the viewer to simultaneously embrace rest represented by the pillow and relate the concept of rest to the herbs, and by extension connecting rest to our relationship to the earth.

Working primarily in sculpture with found or used objects, I was drawn to exploring video because of the sculptural elements and materiality of access in video work. (Along these lines, a work that has influenced me a lot is Carolyn Lazard’s video A Recipe for Disaster which layers multiple sources of audio and text over Julia Child’s show The French Chef from 1963 which was the first appearance of open captioning in US broadcast TV.)

Like a lot of my other work, I don’t mention disability specifically but instead use disability aesthetics and embrace the anti-capitalist nature of disability by exploring rest, crip-time and other anti-capitalist ways of experiencing time. In the context of this video, it can be in the pacing of the video itself, noticing and reconnecting with the plants around us, or healing through non-western orancestral medicine, and access to cultural and familial traditions. I’m also thinking about slow looking, and relationships to plants as a form of access for neurodivergent people specifically considering how overwhelming society can be for us.

More recently I’ve become interested in using ergonomic furniture as a sculptural object in my practice which is designed for efficiency or comfort in the office or work environment as a site of commodified rest, further normalizing exploitative work conditions and expectations. I feel that video work like Arranged with Care juxtaposes or compliments these themes in my sculptural practice because it allows me to explore time and the environment outside of work culture that is inaccessible and unsustainable to me as a disabled person but also for the majority of workers as well.

Alex also generously shared these general thoughts on their creative approach.

A few artists that have been a huge influence to me and my practice are Park McArthur, Constantina Zavitsanos, and Carolyn Lazard. When I was learning from them in grad school they helped to shift the way I view my practice, what constitutes as “the studio”, and what constitutes as “the process”. They expanded where the art making starts and stops for me, or rather doesn’t have a start or a stop.

A good example of this is Constantina Zavitsanos’ I think we're alone now (Host), a yellow-beige curved memory foam mattress topper inside of a rectangular wooden frame which leans against a wall. The materials list includes- Full-size memory foam mattress topper, wood, eight years’ sleep with many. It’s important to note the eight years of sleep with many people as an essential part of the materiality of the piece. As the Brooklyn Museum explains, “The residue of sleep, sex, and rest suffuse Constantina Zavitsanos’s minimalist and poetic sculpture. Constructed from a used mattress topper, the work holds traces and permanent imprints of varying forms of togetherness shared by Zavitsanos and others over the course of eight years. By coupling ideas of being alone with another person and the multiple meanings of hosting, the title evokes dependent and hospitable forms of “getting together” and “getting away” to consider the nature of intimacy.”

Since coming into my identity as a disabled person in grad school, I have been especially aware of and interested in time spent with others, the labor of embodiment as a disabled person, and the ephemera or residue of that time and labor. I aim to depict the materiality of interdependence, at least in some of the ways that it shows up in my life. This could be the accumulation of pill bottles, sweat stains on a bedsheet, a pile of books, used joint filters and ashes from years of smoking weed at the end of a workday, a jar full of used single use contact lenses, etc.

Sometimes it’s not an item that I’ve actually used but instead time piles up in other ways. My piece EXTRAHERE for example, is a continuous red thread with countless pairs of coffee beans glued together, no more than a half inch apart, like beads on a necklace and wrapped in layers around a wooden cable reel. I started gluing coffee beans together on the red thread around June of 2020. I started doing this thinking I would make a wearable object but the thread kept going and going. I found it to be both a meditative process, and a way to stim. Thinking about how coffee is an often overlooked or normalized symbol of work culture, I found this process to also be a rejection of urgency.

I’m thinking about our 24/7 society and how our rest time is continuously folded into capitalism. An example of this might be scrolling social media and that leisure time being turned into profit even if we might not be aware of it. Jonathan Crary explains the power of sleep in 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. He says, “Sleep is an uncompromising interruption of the theft of time from us by capitalism.” And citing Marx he explains, “The first requirement of capitalism, he wrote, was the dissolution of the relation to the earth. The modern factory thus emerged as an autonomous space in which the organization of labor could be disconnected from family, community, environment, or any traditional interdepencies or associations.”

To reclaim or embrace rest, slowness, and understanding access and interdependence as a material both brings me closer to the environment and helps me understand myself in relation to a legacy and lineage of disabled mentors and disability history. In her book Crip Kinship: The Disability Justice & Art Activism of Sins Invalid, Shayda Kafai quotes crip-ancestor Stacey Milbern, who explains that “the work of supporting people rebirthing themselves as disabled or more disabled has a name. We are doulas.” Kafai expands, “Crip doulas stress that we do not grow into our present or our futures on our own; we move into these places with love and mentorship of our community. Together we rebirth ourselves into our disabilities or into our shifting bodyminds. We do this work with celebration and with struggle, we never journey alone.”

My practice is how I move through and process the world. Many of my interests stem from an inability as an autistic and chronically ill person to sustainably work a full time or regular job. My capacity and relationship to work is something that I am forced to confront everyday. I think this is one reason I tend to move away from displaying or spectacularizing specific diagnoses (that said, telling our stories is important and necessary) and instead often depict the tension between our needs and standards of productivity and embodiment. Consequently, I’m interested in collectively embracing our needs as a way to be together and love each other. The understanding that “access is love”, a project by Mia Mingus, Alice Wong and Sandy Ho, has deeply impacted me.

Comments