Xixi Edelsbrunner / Blank form

- Bert Stabler

- Jul 28, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 1, 2025

“The naturalized repudiation (…) of non-normalized bodies is signified by the (continuing) popularity of narratives about reforming, erasing, reclaiming, perfecting, and overcoming body limitations and the various forms of stigma with which they are associated. Such constructions normalized the assumption that the disabled, old, and obese should defer to those who are non-disabled, slim, and young.”

Debbie Rodan, Katie Ellis, and Pia Lebeck, from Disability, Obesity and Ageing: Popular Media Identifications, 2014

“I love the disabled villain archetype, and I’m pushing myself to be more nefarious”, Xixi Edelsbrunner told me. The trope Edelsbrunner refers to could extend at least back to Richard III, and later to Long John Silver and Captain Hook, but particularly connotes infamous disabled antagonists in Hollywood cinema: from Darth Vader, Dr. Strangelove, and Jigsaw to any number of James Bond villains. It can be extended to other villains who are mentally ill, visibly disfigured, and/or have replaced or covered body parts with mechanical or otherwise artificial devices: Freddy Kruger, Voldemort, Hannibal Lecter, Frank Booth—or, for that matter, the Terminator. A revelatory example Edelsbrunner shared with me is found in the campy yet unsettling 1971 horror-comedy The Abominable Dr. Phibes, in which the titular evil genius and exemplary disabled antihero, played by Vincent Price, mysteriously speaks through a gramophone horn while pursuing an elaborate plot to wreak vengeance upon a group of doctors. Edelsbrunner expressed that in beholding these disabled villains, curdling in their pain and frustration, “the bitterness feels very true.” I would add that impairment offers both the villains and the audience a pretext for undermining received presumptions of human empathy by leveraging the uncanny potential of body differences and prostheses.

The menace of Frankenstein’s monster isn’t only that a living thing has been made artificially, but also that artificial objects are given organic life. Modernist art mapped this tension on to that between Walter Benjamin’s auratic work of art and the profane utility of mechanical reproduction. Writing in Artforum, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh cites a 1912 conversation in which Marcel Duchamp, who would become known for exhibiting industrially produced objects, asked the sculptor Constantin Brancusi if he thought he would ever make something as beautiful as an airplane propellor. While Duchamp’s provocation could be said figuratively to have inspired Andy Warhol, Sherrie Levine, Gabriel Orozco, Josh Kline, and countless others, Duchamp’s dare was taken up literally by Philip Johnson in his Machine Art exhibition at MoMA in 1934, which included an outboard propellor among the hundreds of manufactured items on display. Though he did not avow his disabilities (among them stuttering and bipolar disorder), modern art may have had no more prominent villain than Johnson, who actively and vocally supported and collaborated with Germany’s Nazi regime.

But the power-trolling spirit of true camp, rather than the campy power worship of fascism, describes the ethos of John Waters, who had a character in his film Desperate Living complain: “You know I hate nature! Look at those disgusting trees, stealing my oxygen.” In this contrarian spirit, Edelsbrunner told me that they find a deep fascination in the McMaster-Carr online hardware catalog, regularly utilized by builders and engineers, inasmuch as its inhuman vastness, mundane design, and organizational precision all connote aspects of the bewildering financial, technical, medical, and legal systems they rely upon. Edelsbrunner told me, “It's disturbing, because these systems are antagonistic to me in my life, but also because, in my heart of hearts, my truest wish is for perfect bureaucracy.” They told me of scoring one lone victory in contesting a denial of coverage: “The guy on the phone was like, ‘I'm really happy to tell good news for once, cause this never happens.’” Relying for comfort, mobility, autonomy, and survival on artificial devices and industrial products, while spending endless hours in negotiation with medical insurers and other service providers to obtain vital necessities, it is understandable that nearly any disabled person in a wealthy country might simultaneously fantasize both a perfectly effective system of health care, and a perfectly efficient system of revenge.

Contemplating these dystopian fantasies is helpful in parsing Edelsbrunner ‘s exaggeration of the aggressively functional aesthetic of medical hardware. Measuring over 20 feet in length, their 2022 piece Untitled (Long Greige Sculpture) basically resembles a wildly stretched-out walker, effectively turning a mobility device into a barrier. This was comically literalized in an incident relayed to Edelsbrunner secondhand, in which a visitor entered their show not wearing a mask, although masking was requested on a posted sign; upon noticing all of the masked attendees, the visitor tried to hurriedly exit and reacted dramatically upon being waylaid by Untitled. “Inducing panic in someone is a gift that is worth so much more to me than everyone masking from the get-go,” they told me. A companion piece to this could be Moving as Some Thing, an interactive 2022 assemblage whose title comes from an essay by performance theorist Andre Lepecki. Composed of metal tubing and elements from multiple rolling walkers all linked together, the work for Edelsbrunner is intended to represent “how our habits of movement change with mobility devices,” while through its resistance the object itself “asserts its sense of agency”. This menacing agency of the object becomes more overt in Totality of All Bodies, three larger-than-life backlit pieces on black, all of which feature a quasi-Vitruvian graphic of a semi-androgynous human figure, familiar from forms on which patients are asked to indicate sources of pain.

Edelsbrunner’s most enigmatic recent artworks may be their Monoprints series. These cast polymer sculptures are made from discarded vacuum-formed plastic packaging, forms that do not reproduce but distantly echo the contours of the products contained within. Some earlier sculptures in this series were lavender, aqua, or pink, but recent iterations have been gray and off-white; some were mounted to the interior walls of a small box, as part of Annetta Kapon’s Proxy Gallery project, while others are shown individually on pedestals. Edelsbrunner describes the pieces as deliberately “boring”, and, as such, very much invested in a project of tricking the viewer. These small simple abstractions require an observer to focus long enough to visually separate the artworks from the anonymous functional surroundings in the white cube gallery, a setting the artist has compared to the sterile environment of a hospital.[i] This stealthy unsettling, or disabling, of the gallery’s negative space is nicely underscored in a recent exhibition, where Edelsbrunner added nondescript beige frames around the power outlets; these frames highlight utilitarian blemishes, often accentuated by accidental drips of paint, in the otherwise pristine visual substrate. And recently they’ve turned their attention to the conduits, pipes, and ducts that crisscross gallery ceilings; “you’re not supposed to look up”, they said to me, “which I think is the funniest thing.”

The origin point for Edelsbrunner’s recent works comes from a series of photos taken between 2020 and 2022 entitled Numbness and Tingling, in which they began to document elements of what they term the “generic” while waiting to see various medical practitioners. Following Gean Moreno and Ornesto Oroza's concept of "generic objects”, Edelsbrunner’s generic images are defined by an anti-aesthetic of pure functionality, objects and spaces adorned in neutral hues, constructed in durable but inexpensive materials, designed to be sturdy, stackable, interchangeable, modular. Cropped in a manner both elegant and offhand, the shots in this series reveal abstracted empty corners and vignettes in medical spaces, ambiguous forms and surfaces suggesting a drainpipe, a fluorescent light fixture, a worn tan plastic handle, a reflection in a scuffed steel surface, or an hourglass-shaped brown object next to a sink. In their blank, haphazard formalism, these timeless interiors convey in glimpses the bland, banal purgatory of waiting to be seen.

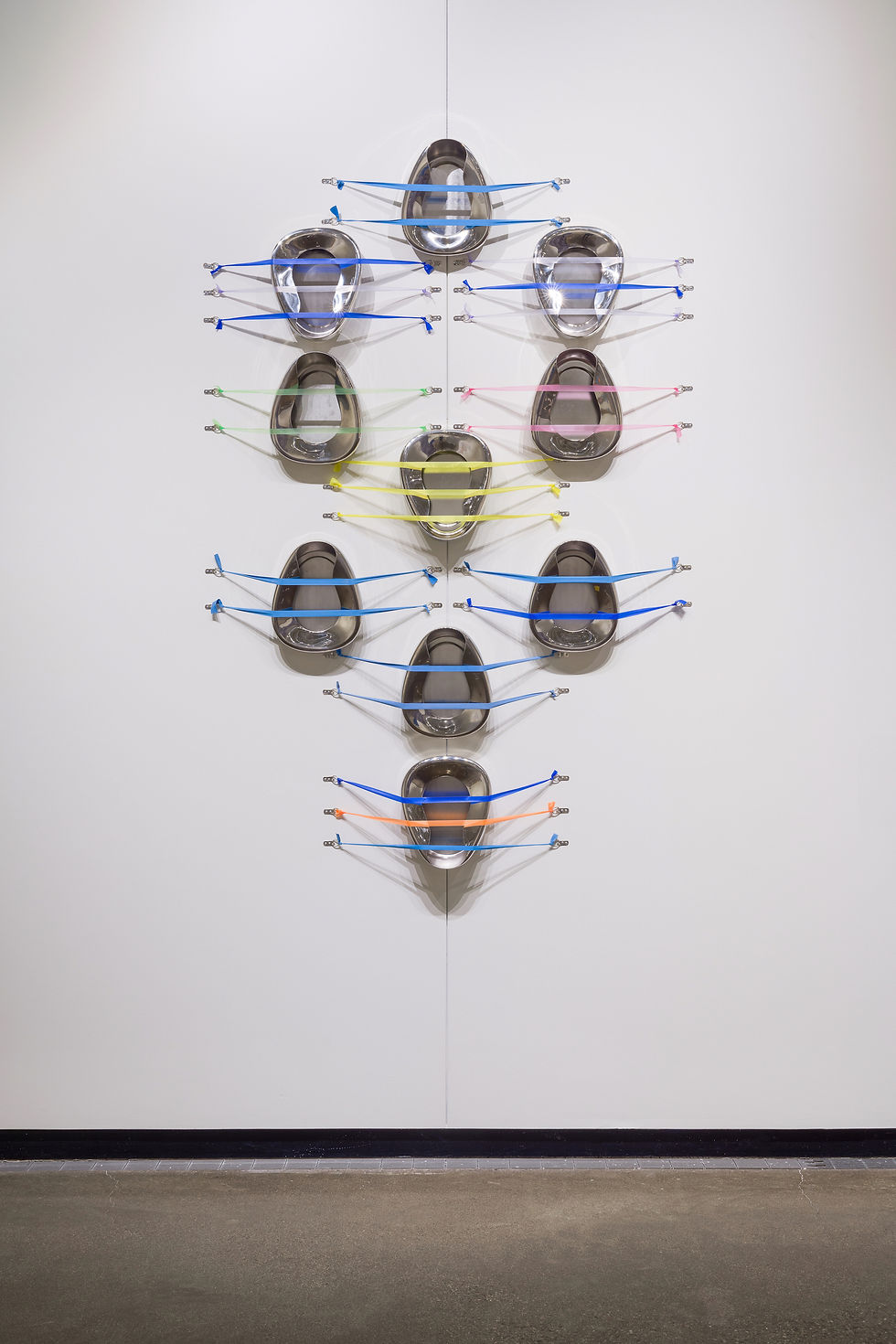

These austere semi-abstractions represent Edelsbrunner’s more passive affect, while their turn to covert aggression begins to emerge in The Choice is Yours, from 2024. This wall-mounted reflective disc has something of the character of a classic doctor’s head mirror, or of the convex mirrors posted high in the corners of hospital hallways. Resembling the shape of a flattened Hershey’s Kiss, as Edelsbrunner describes it, the image will distort and divide a viewer’s image as they approach—and if they lean too close, the viewer risks impalement on a sharp needle protruding from a brightly-lit hole at the work’s raised center. When presenting this work in our 2025 disabled artist symposium, Edelsbrunner noted that. while all other work in this exhibition was hung at a level most amenable to viewing from a seated position, with wheelchair users like themselves in mind, The Choice is Yours was hung at standing height. As they told me, “it's kind of hard to make work that is both antagonistic and also accessible.” But for an upcoming exhibition this fall, they are planning on adopting an even more confrontational stance, inspired in part by Harry Dodge’s 2002-17 series Emergency Weapons.

While Edelsbrunner is actively aligned with emancipatory projects in and beyond disability justice, the pessimism of their work is inseparable from its appeal. Like disabled artists such as Carolyn Lazard and Constantine Zavitsanos, Edelsbrunner’s work refuses spectacle and avoids any display of strenuous craft, allowing the minor gesture to suffice. But unlike many disabled artists, Edelsbrunner’s work is coy, even snarky. I admire the resolutely affirmational and solidaristic approach of many disabled artists, whose celebratory and reparative works offer viewers alternative worlds, images of refuge, or sincere expressions of protest. But Edelsbrunner offers no reassurance. And just as they eschew comfort and pleasure, their pieces also don’t seek to confront the decades of brutal neglect that defined state-run asylums and other institutions for warehousing disabled people. Rather than looking to a possible future or a traumatic past, Edelsbrunner’s work instead looks to the present. Their prosaic objects aptly epitomize the legacy of state abandonment In the U.S., where, at least for the time being, Auschwitz has been replaced by Amazon.

Comments