Ezra Benus / Nomad exegesis

- Bert Stabler

- Sep 4, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 8, 2025

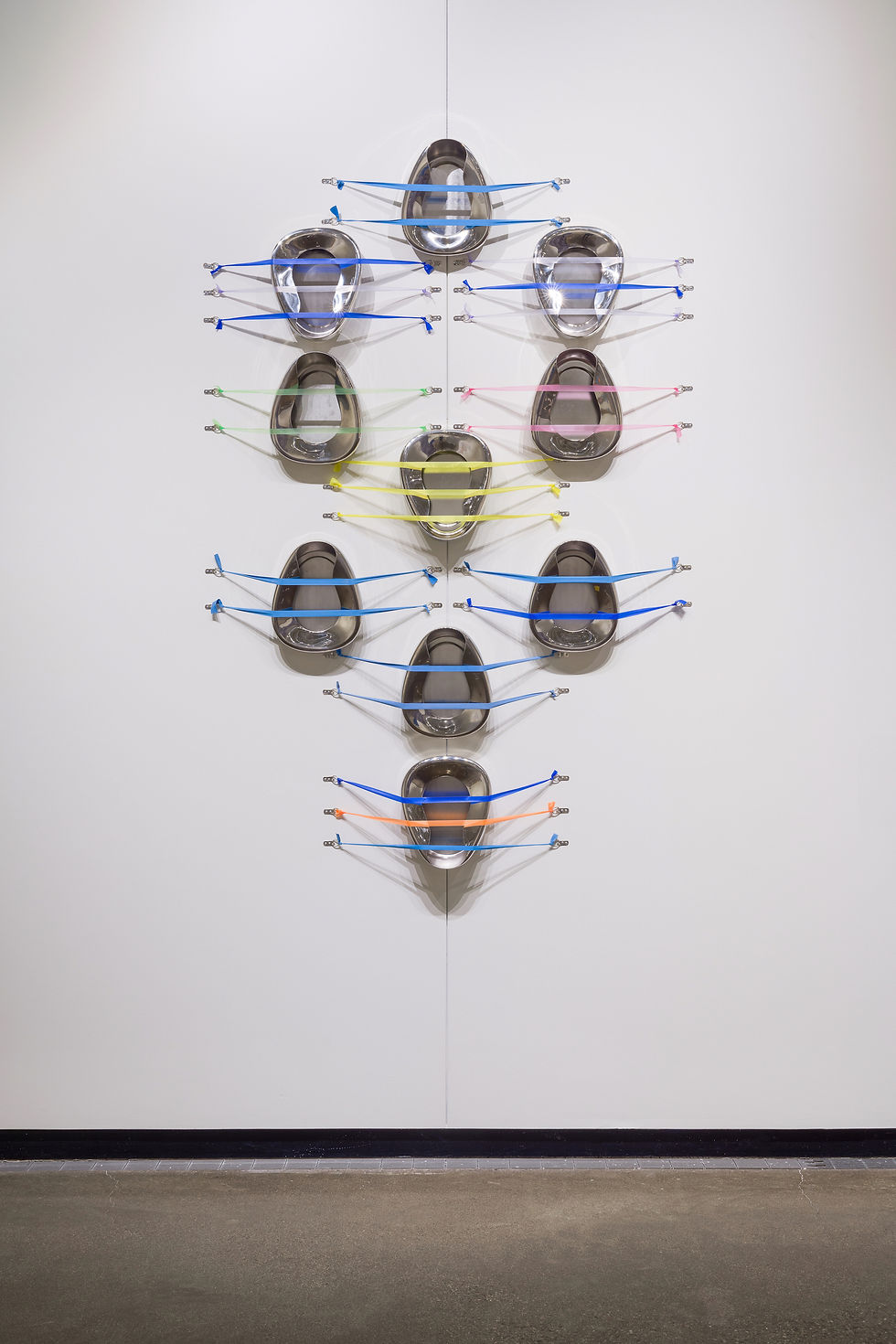

Presenting the writing of the Jewish author Franz Kafka as exemplary of “minor literature”, or literary works written by members of minoritized groups, Gilles Deleuze argues for an understanding that diverts from a stable or transcendent symbolic system. “No less than all designation,” Deleuze writes, “Kafka deliberately kills all metaphor, all symbolism, all signification.” In discussing his 2024 piece Relax (Sefirot/Tree of Life), ten vintage aluminum bedpans held against the wall with tourniquets in an arrangement which recreates the Kabbalistic tree of life, known as the Sefirot, the chronically ill artist Ezra Benus asserted that all of the objects in his work, whether related to bodily care or Jewish ritual, are things which he has made use of in some way in his own life. He clarified this because, as he put it, “A lot of times in our art worlds, people use objects as fully metaphor, not as an actual material reality of disability life.” As noted in Benus’s online portfolio, the tree of life denotes many things at once; it “connects the physical and metaphysical”, as each of its ten points “connote(s) a divine attribute which maps onto the body, echoing the notion that humans contain divinity through our bodily form,“ while it simultaneously “counters negative associations of the common bodily experiences of illness (as ‘gross’)”, and points at “the relationship of medical fetish and kink/BDSM”. Also reminiscent of the Sefirot, Deleuze notes that the multivalent nature of Kafka’s writing expresses “a circuit of states which form a mutual becoming, within an arrangement that is necessarily multiple or collective.” Or, as Benus put it in conversation with me, “I’m connecting us through pain.”

An earlier work by Benus that also connects spirituality with bodily care objects is the interactive 2019 assemblage You Shall Rejoice / ושמחתם. The work incorporates a magic wand vibrator, a small painting, and a heating pad sitting on a shower chair. While both a text and a painting are included in the piece, it centers on the chair, pad, and wand, not merely displayed as inert readymades but made available for use. The tactile invitations offered by these mundane but necessary palliative objects further underscore the direct and utilitarian dimension of Benus’s assemblage works. “That’s how Torah study happens”, he told me. “You go into the literal, you read the literal.” He continued: “And then you see the messages behind the literal, you see behind each word, behind each letter, behind the ways words are put next to each other… the way that stories are connected, someone's ideas are referencing someone else's ideas from different generations.” The objects on the chair are accompanied by wall text which reads as follows:

Here we find care as joy

Here we find pain as joy

Here we find pleasure as pain

Here we find pain and pleasure

Here we know pain and pleasure and rest

Here we find disability/sickness/illness as ritual

(Note to visitor: Please take care, use objects as needed and wanted.)

As Benus states in his portfolio, the work references the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, during which, as the Torah directs, “You shall rejoice.” The wall text enacts this Talmudic process of hermeneutic iteration, reading back and forth between the literality of the Torah text and the functionality of the objects in the gallery, in the blended contexts of pain and ritual. “The objects are not abstract,” explained Benus, “but then the concepts become abstractions from the object, to then explore different kind of conceptual things, and also we abstract them from their usual use, and that to me is abstraction in a way as well.”

Relax (erotic hypnosis), 2023, painted text, magic wand massager, vintage "Relax" brand bed pans,

sound, vibrations. dimensions variable. (Left: installation view at Migros Museum, Zurich; right: detail)

In conversation with me, Benus emphasized not only the various levels of meaning contained in these objects (the heating pad, the massage wand, and the shower chair), but also their portability and affordability, as well as their availability without a prescription. Invoking another term familiar from Deleuze’s writing with Felix Guattari, for Benus these aspects render the objects “nomadic”, unfixed both in space and in their intended function. In particular, other works of his also make use of vibrating massage wands, which can be used for both pain relief and erotic stimulation. Nomadic wandering is literalized kinetically in the 2023 assemblage Relax (erotic hypnosis), in which a massage wand hangs down by its cord from a large protruding panel and moves in a circle, audibly encountering three overturned bedpans arranged on the ground; the large panel bears the logo of the long-defunct company Relax, which manufactured the bedpans, with the whole installation suggesting both an absurd advertisement and a kinky ASMR reel. “These bedpans (are) the things that connect all of us… we all shit, piss, and bleed, right?” Benus asked when presenting this work at the Disabled Artist Symposium this past April. “We all have the potential for pain and pleasure, and these bodily functions.” The overlap of pain and pleasure is even more cheeky in Relax (Magic Mic), also from 2023, in which three massage wands are set up on microphone stands. The wands’ vibrating bulbs are pierced by medical irrigation needles, which call to mind the medicalized erotics practiced by the chronically ill artist Bob Flanagan and his partner Sherree Rose, albeit by wry association rather than the immediacy of a literal body—a figurative approach in keeping with Deleuze’s literary understanding of masochism.

The remaining item in You Shall Rejoice, the small abstract acrylic painting that accompanies the chair, pad, and wand, points to a less apparently literal area of Benus’s creative practice. Perhaps the most explicit reference to Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy is in the title of one of his standalone abstractions, the large 2018 canvas (Medication 6) Body Without Organs, Intensities Such as Pain, in which vivid narrow triangular shards float in a fiery red void. Suggestive of hospital curtain and gown fabric, this pattern reappears in three color schemes in the 2019 piece You shall observe it as a festival throughout the ages, a set of planks used to create a family abode during the holiday of Sukkot, and the 2020 series SUN / MOON // שמש / לבנה iterates this pattern over seven panels to represent the days of the week. In a philosophical discussion of mystical conceptions of the body, scholar William Behun writes: ”When we think of the BwO (body without organs) as the plane of consistency or smooth plane over which intensities flow, we are using terminology that bears a marked similarity to descriptions of spiritual unity given within the religious tradition.” Making a point even more germane to Benus’s practice, he states: “Matter and spirit are not two separate individuals, but exist along a range of intensity wherein we understand matter as solidified or fixed spirit, and spirit as rarefied matter.” In keeping with this continuum, there remains a material, literal element even in these hard-edged abstract works, as the palette is based entirely on the colors of pills that Benus has taken over the course of many years.

(Medication 6) Body Without Organs, Intensities You shall observe it as a festival throughout the

Such as Pain, 2018, acrylic on canvas. ages, 2019, each plank is 8ft x 2.5 in., acrylic on wooden planks from family Sukkah (a temporary abode structure built for the holiday of Sukkot)

“In the process of making a BwO (body without organs),” writes Behun, “one experiences oneself no longer as a molar person but rather as a molecular event, a smooth plane in which intensities and flows pass without restriction or limitation.” Appropriate to his spiritual, theoretical, and political detachment from egoic individuality, Benus has made a number of his works in collaboration, most frequently with his brother Noah as the collective identity Brothers Sick. Symmetrically arranged high-contrast grayscale photographs are layered with graphic elements or bold text injunctions in print works informed by graphic design, intentional planning and messaging taking the place of the intuitive improvisation Ezra Benus employs in his solo work. In Pareidolia (Vaccinate Now), from 2021, an array of silhouetted figures bearing syringes alternate in a hypnotic pattern of inverted monochrome gradients with the verbal imperatives “End vaccine hoarding”, “Global inoculation against viral fascism”, “End eugenics”, “Stop rationing care”, “Stop medical apartheid”, and “Vaccinate now.” For the world eternal / לעולם ועד [l’olam va’ed] is a print that wraps around a freestanding wall, a grid in which photos of forearms in mirrored diagonals rhythmically alternate between being wrapped in medical tourniquets or in tefillin, cords which are “bound on to arms by Jews during weekday morning prayers.” The phrase “l’olam va’ed”, or “forever and ever”, appears in Hebrew characters at some intersections where these photographs meet, while other intersections faintly show a black triangle, the Nazi symbol for a range of populations designated as disposable, including the sick and disabled.

Pareidolia (Vaccinate Now). 2021. Brothers Sick For the world eternal / לעולם ועד [l’olam va’ed],

(Ezra and Noah Benus). photograph on aluminum. 2022 (detail). Brothers Sick (Ezra and Noah

Benus), freestanding wall sculpture covered with

digital print on vinyl.

Benus proudly acknowledges the influence on these works from art made during the early years of the American AIDS crisis, by groups such as Gran Fury, the Silence=Death Project, and ART+Positive, as well as individuals including Gregg Bordowitz, Avram Finkelstein, Hannah Wilke, and Felix Gonzalex-Torres, and he has more recently found inspiration from the works of Jo Spence, Donald Rodney, and Hamad Butt. “I love talking about influences, because I think this is actually something like that feels for us deeply Jewish,” he told me; “We view our work as Torah exegesis, as commentary.” Both as an individual artist and in his collaborative projects, Benus’s work relies equally on elements that are literal and figurative, sensory and linguistic, profane and spiritual, formal and conceptual, active and reflective, accessible and esoteric. Referring to the mystical legend of the humanoid golem, Benus explained,

It could be called using Jewish prayers, incantations, and also writing with this word emet, which is the word truth. three letters. The word emet, when you take away the 1st letter of it. aleph. You have the word that just says met and met means death, or to die. We say the only truth that we know is death.

Whether it be in the Holocaust, from AIDS, from COVID, from the genocide in Gaza, or any other cause, natural or manmade, this truth is known but never understood. “I try to understand as much as I can about what's going on with me, or why the world is then set up in a way where it's so hard to figure out what's going on with me,” he told me. “And then there's a moment of, we can't explain a lot of things. Sometimes they just happen.” “I think disabled people have a penchant for living with death in a different way,” Benus concluded. “It’s just a matter of paying attention to it.”

![The image features a pattern in which two diagonal black and white photgraphs of forearms in dramatic lighting repeat and alternate in such a way as to forma rhythmic pattern. One arm wrapped and bound with an intravenous medication and the other arm is wrapped and bound with tefillin, Jewish ritual object of black leather straps that contain prayers written on parchment hidden in a box located on the bicep, worn during morning prayers as an act of boundness with the sublime. In the center of the image is a black triangle, referencing the badge designating sick, disabled, Roma, Sinti, and other people deemed by Nazis as asocial or not fit for work, a history intertwining eugenics, ableism, anti-semitism. Two Hebrew words form the phrase לעולם ועד [l’olam va’ed] that translates as ‘forever and ever’. The phrase is excerpted from the recitation from a morning prayer, that connects through prayer the idea of oneness and eternal connection of the individual with the sublime/divine as a collective.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/8172d4_10b18f5a13e144369f4b07e002d2b4f9~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_167,h_250,al_c,q_30,blur_30/8172d4_10b18f5a13e144369f4b07e002d2b4f9~mv2.jpg)

![The image features a pattern in which two diagonal black and white photgraphs of forearms in dramatic lighting repeat and alternate in such a way as to forma rhythmic pattern. One arm wrapped and bound with an intravenous medication and the other arm is wrapped and bound with tefillin, Jewish ritual object of black leather straps that contain prayers written on parchment hidden in a box located on the bicep, worn during morning prayers as an act of boundness with the sublime. In the center of the image is a black triangle, referencing the badge designating sick, disabled, Roma, Sinti, and other people deemed by Nazis as asocial or not fit for work, a history intertwining eugenics, ableism, anti-semitism. Two Hebrew words form the phrase לעולם ועד [l’olam va’ed] that translates as ‘forever and ever’. The phrase is excerpted from the recitation from a morning prayer, that connects through prayer the idea of oneness and eternal connection of the individual with the sublime/divine as a collective.](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/8172d4_10b18f5a13e144369f4b07e002d2b4f9~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_433,h_650,al_c,q_90/8172d4_10b18f5a13e144369f4b07e002d2b4f9~mv2.jpg)

Comments