Ariella Granados: Disabling utopia

- Bert Stabler

- Jul 23, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 5, 2023

Ariella Granados, No Documents (video still), 2021

Michael O’Rourke writes that José Esteban Muñoz “aspired to the making of queer worlds and to the framing of an aspirational politics of ‘queer world-making’ in the form of a ‘dream work’ in which worlds are as palpable as things.” Alex Kitnick describes video art as “a slippery art that might sneak outside art…, turn people around (maybe even on), and deliver them to some not-yet-quite-defined third space that would be neither life nor art but some heightened consciousness (.)” BIPOC queer communities of mutual support have long insistently expressed their world-making through art, in the sense whereby O’Rourke draws on theologian John Caputo’s sense of the “insistence of God.” Invoking the now-commonplace magic of video while also drawing on the visual language of social media mythology, artist Ariella Granados modestly but insistently generates both worlds and consciousness, both in communal projects and in solitary reconstructions of her own history and embodiment.

I Used to Have Cable Before He Left (still from video series), 2019

I Used to Have Cable Before He Left (still from video series), 2019

Labor Like My Mother's (video stills), 2021

In 2019 Granados started creating videos about her parents, in response to having learned at age 15 that her stepfather was not in fact her birth father. In her series I Used to Have Cable Before He Left, as well as the standalone No Documents, she ingeniously depicts her mother, her stepfather, her birth father, and herself. Subtitles are used creatively and humorously to translate her family members’ Spanish dialogue, as well as her own internal and external monologues, through which she both empathizes with and comments on her family members, while referencing tropes of Mexican telenovelas and TV news. Along with clever editing, Granados makes ample use of her background as a professional makeup artist to single-handedly portray multiple roles, now a staple practice among TikTok creators. And in the more understated 2021 video Labor Like My Mother's,

Granados simply recorded herself doing the domestic chores her mother would do, cleaning and ordering her space.

Bodies in Progress (example from photo series), 2020

Bodies in Progress (examples from photo series), 2020

In Bodies in Progress, a photo series from 2020, she continues cleverly spoofing television formats familiar from her childhood, including ads from Herbalife, TBN, and the Home Shopping Network, while in her ongoing series of infomercial-style videos and performances, entitled 1-800-INACCESSIBLE, she struggles to use kitchen implements. This struggle with mundane tasks becomes eroticized in the series Eating With Desire, wherein Granados seductively opens name-brand packaged snacks with her teeth in lingering closeup shots. All of these advertising-themed works cleverly hint at the operationalization of influencer niche-marketing, alongside critical commentary on the exclusion of queer, Brown, and disabled bodies.

1-800-INACCESSIBLE (video still), 2021

Eating With Desire (video still), 2021

Perhaps hinting at Muñoz’s influential book Cruising Utopia, Granados’ final project this year as the first-ever artist in residence with the Chicago Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, through the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs, was entitled Disabling Utopia. In this work, volunteer disabled contributors created miniature sets which they then performed in as backdrops, through one of Granados’ signature tools, that of the green screen. She has recently parlayed chromakey symbolism into creating a fully green “alter ego,” erasing distinctions between herself and her environment in a provocative literalization of the social model of disability. Granados also speaks of ASL interpreters and live captioners as performance artists, figures whom she intends to meaningfully integrate into her future productions “as another element of the performance,” while also incorporating music and experimental graphic scores.

Subverting Otherness, part one (video stills), 2021

In the first video where Granados plays with chromakey, she paints her face green, revealing a portrait of her mother as the background. In another she paints her arm green; the shape of the painted arm is filled by static, while Granados is isolated in a bustling London crowd. The arm Granados paints in the video is paralyzed by Erb palsy, a condition acquired at birth. “I think of the color green as a way to render my body,,” she says. “In post-production, green is used as a way to render space… By using the color green… I use it as a way to take agency over my body and to reclaim my body again.” Subsequently, Granados did a video in a full-body blue morphsuit, topped off with a jacket and wig, and later painted her arm as a 2021 public performance, entitled Subverting Otherness, in front of a church in Puebla, Mexico. She saw this performance as an act of protest, saying “I was learning a lot about the Spanish colonial time, and how bodies were treated if they didn’t adhere to European standards… I don’t think a body like mine would have been honored, or treated well.” Granados later did a similar painting performance in Chicago while dressed in a hospital gown, a wig, and her blue morphsuit, with an assistant dressed as a nurse.

Subverting Otherness, part two (video still), 2021

Untitled (video still), 2021

These videos underscore the complexity of the claims Granados makes on her body through the device of chroma key. Through paint or costuming she literally makes herself invisible, mirroring the personal invisibility she used to seek out as an insecure disabled young person, but conversely, also the official invisibility she has confronted as an adult in multiple attempts to assert her identity and acquire disability benefits. Currently Granados has a range of ideas for installations integrating sculpture, video, music, and performance, all referring insistently to the blue and green monochromes that literally embody the notion of being “under erasure.” And she intends to continue performing this erasure collaboratively in community spaces. Through her residency with the MOPD in Chicago, Granados said, “I’ve learned that I have a skill for programming… with really thinking about accessibility and inclusivity And I would hope to continue doing this kind of work.” She has been a resident DJ with a regularly scheduled sober queer dance party called Lez Get Together, and she reflected on nightlife in Chicago, saying that “there’s still a lot of work to do in regards to making sure that those spaces are accessible, safe and comfortable for people with disabilities.”

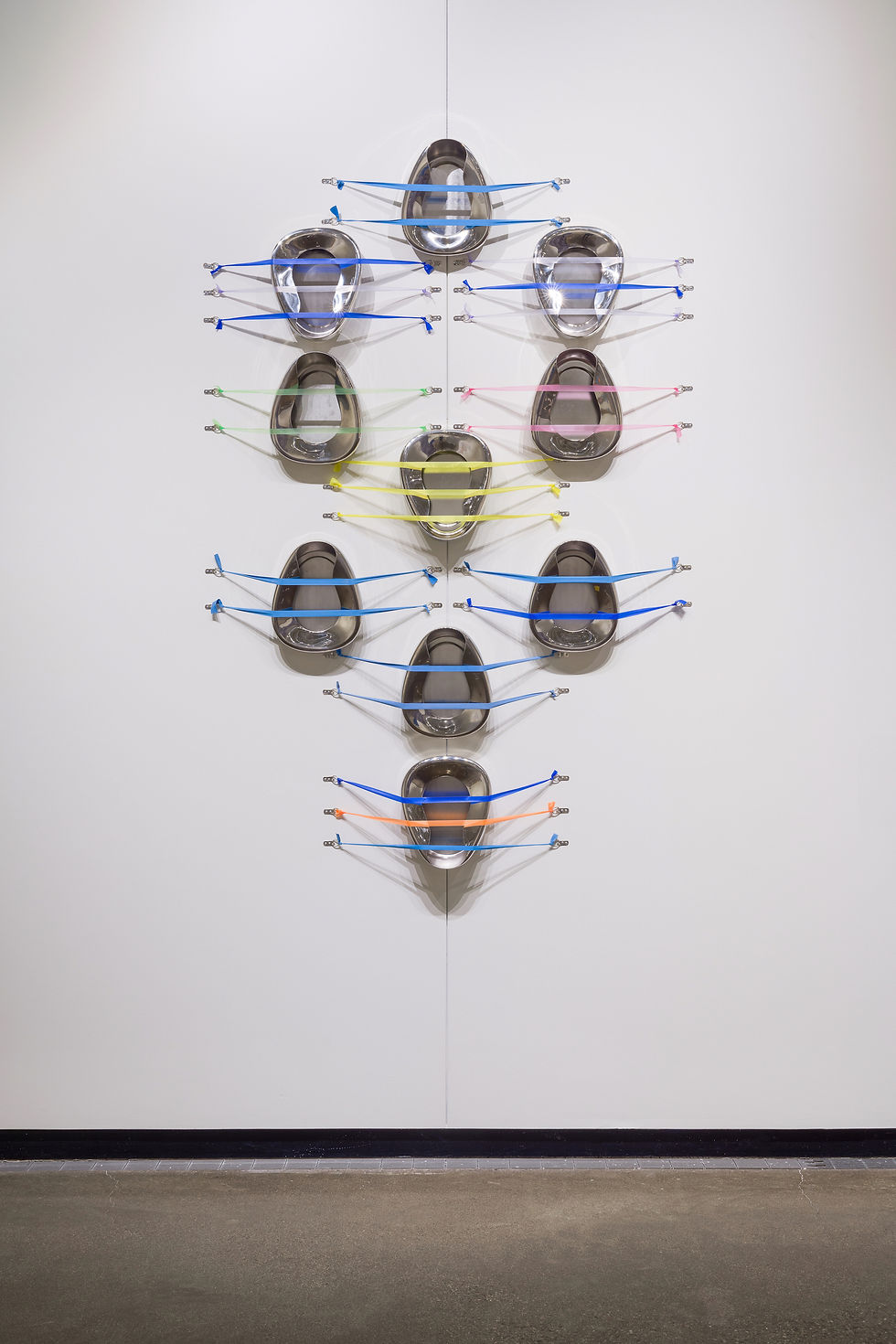

Project sketches, 2023

Another artist known in part for visibilizing the invisibility of domestic work, particularly in her iconic residency project with the New York Department of Sanitation, the feminist artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles writes in her 1969 Maintenance Art Manifesto that “Maintenance is a drag. The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom. The culture confers lousy status on maintenance.” “The exhibition of Maintenance art…” she continues, “would zero in on pure maintenance… My working will be the work.” But transformed through ideas of queer community and crip time in the work of artists like Granados, the “drag” of maintenance can take on new connotations of hope, play, and mutual support. “For me my queerness is less about my sexuality,” she says, “but has always more so been about the body that I’m in, it’s more about my disability. My queerness is informed in the way I have to navigate the world, and how I navigate through the world.”

Comments