Sonia Boué / Postmemory work

- Bert Stabler

- Apr 3, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 11, 2025

In reviewing a collection of writings made while D.W. Winnicott was tending to children evacuated to the English countryside during the Blitz, from 1940-41, Joyce Slochower summarizes the esteemed psychoanalyst’s approach to personalized nurturing with an insight that still speaks eloquently to the lives of neurodivergent people. Slochower writes that “imposing anything—even a possible ‘cure’ from the outside in—runs the risk of obliterating the child’s personal sense of aliveness.” In 1937, just a few years before the evacuation of London’s young people, 4,000 Basque refugee children were evacuated to Britan from the port of Bilbao after the Guernica bombing immortalized by Picasso during the Spanish Civil War. The father of British artist Sonia Boué wasn't himself a Basque child refugee, but was exiled as an 18-year-old in 1939 during a period known as the retirada. Paralleling Winnicott, his first job on arrival was to care for Basque children in a colony in Oxfordshire.

Boué’s visual and textual work has dwelled for years on both archiving her father’s life and articulating her own experiences. Self-identifying as a neurodivergent adult before acquiring a clinical diagnosis as an adult, Boué’s art very much aligns with the patient process of self-discovery that Winnicott advocated, while also embracing mutual recognition and supportive collaboration as central aspects of her practice. In her two-person show with Ashokkumar D Mistry, Las Gemelas: Arrival (a lexicon of unmaking), which closed in January at John Hansard Gallery, Boué created what she calls her “most autistic work yet,” an installation and video entitled Look Well After Yourself. Named after her father’s favored parting phrase, the installation portion of the work features 100 slender steel stands sporting brightly colored wool pom-poms, the latter manually fabricated by Boué over the course of three months. The wool was sourced from a factory in the Yorkshire town of Keighley, where 100 Basque refugee children were resettled. While the form of these works evokes the dahlia, a flower imported to Europe from Mexico in the 16th century, the primary inspiration for Boué was the vivid silk fringe that hangs from a common souvenir tambourine from the south of Spain. Boué describes the experience of making the pom-poms as highly sensory, with the wool immersing her in its bright colors, rich odors, and soft textures; as she told me, “It was almost like I could hear the sheep bleating.”

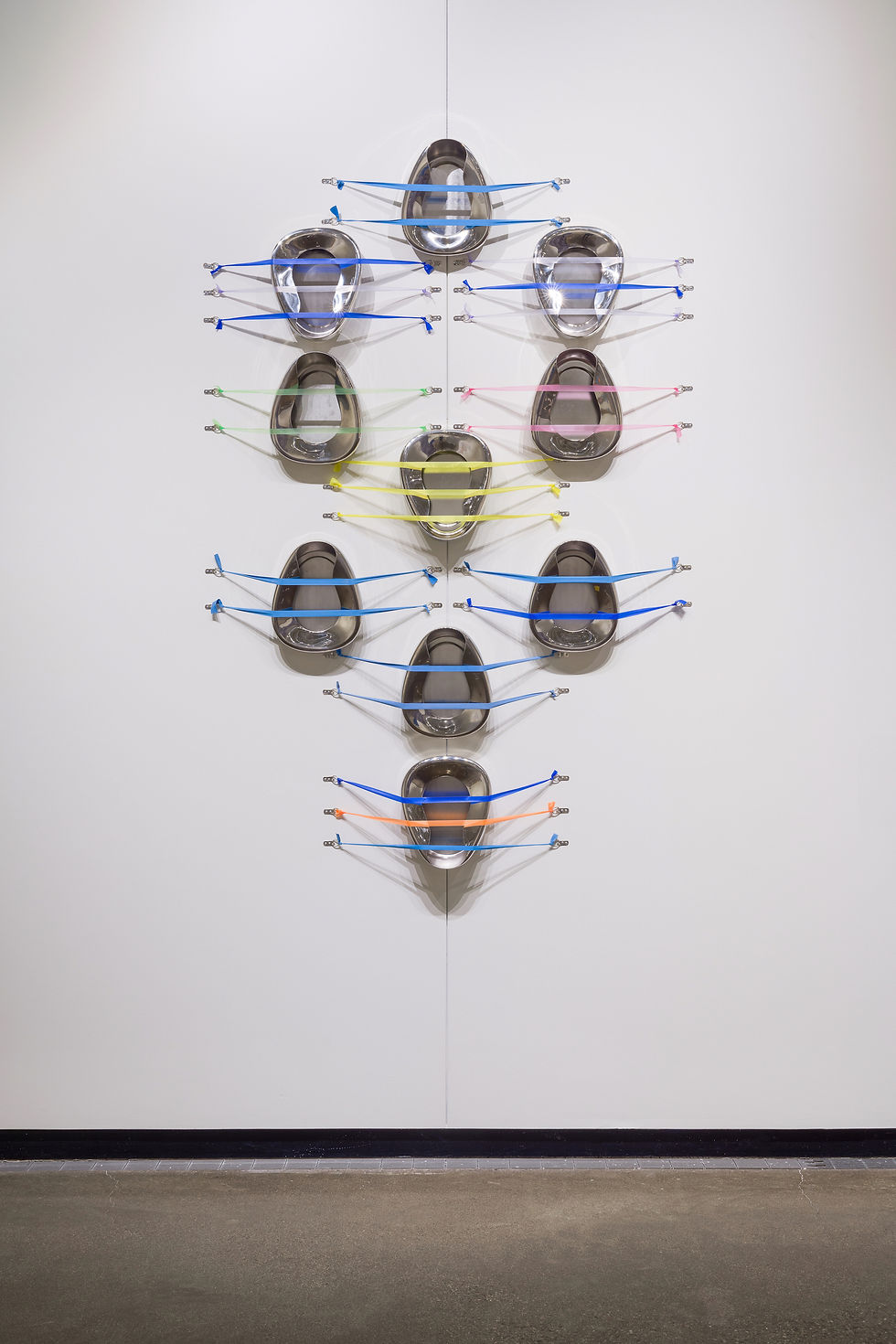

Look Well After Yourself (installation view). Wool, lanolin, and steel, 2024.

Look Well After Yourself, detail shot (left) and close up (right)

The making process is documented in the film accompanying the installation, also titled Look Well After Yourself, which played on a large screen near the entrance to the exhibition. The steady, tightly cropped shots of Boué’s hands and face as she intently and attentively massages and trims the vibrant spheres is strongly reminiscent of a 2007 short film that became a landmark statement of autism culture, Mel Baggs’s In My Language. Baggs, a nonspeaking multiply-disabled genderqueer writer, activist, and artist who died in 2020, is the creator and focus of this earlier film, in which a series of close sustained clips show them rhythmically manipulating and caressing a variety of objects in a soothingly dim domestic setting. Baggs hums aloud, but there is no symbolic speech for a little over three minutes. Then, for about five more minutes, captioned and spoken through their typed interface, Baggs eloquently describes their deep and direct somatic connections with objects, as well as the abusive and alienating experiences that they and others like them confront in encounters with neurotypical people and entities reliant upon narrow understandings of communication. The credits annotate the film as “Acted and sung by A.M. Baggs and assorted objects”.

Look Well After Yourself, still from video, 2024.

Boué recalled having first seen Baggs’s film in around 2014. She described the experience as “mind blowing”, inspiring several of her own early explorations in video, years before she received an official autism diagnosis. “It was the very beginning of me starting to peel away the layers of my practice,” Boué told me, “to actually look at how I worked, not just focusing on the subject matter that I was working on. But to think about how I worked and how neurodivergent that might be.” She feels herself to be revisiting some aspects of these early works with Look Well After Yourself, with both the installation and the video addressing autism not primarily through symbolic representation, the language of neurotypical hegemony, but rather through a process of what amounted to, as she described it, “prolonged stimming.” Along with Baggs, the proximate sources Boué draws on are her own earlier work, in which objects rather than people are the focus of attention. In particular, for her 2021 work The Artist is Not Present, which took the form of a durational online performance edited into a short film, she directly references Marina Abramovic’s landmark performance The Artist is Present. In her performance Boué quietly but unambiguously refuses Abramovic’s aesthetics of endurance and eye contact, qualities inaccessible to many disabled people in general, and neurodivergent people in particular.

Film still from The Artist is Not Present, online performance, 2021.

Studio photograph from The Artist is Not Present, online performance, 2021.

And Boué, like Baggs, is also a prolific author of texts. In Boué’s case, these works often focus on memories and relationships as much as they do on neurodivergence and self-expression. For the collaborative exhibition with Mistry, Boué wrote “More than a briefcase of pills”, a short essay about how Look Well After Yourself was a process of “postmemory work”, of ruminating on and materially working through her father’s stoic struggle with the trauma occasioned by his exile from Spain. She writes: “Such memory care acts –– in which we honour and seek to ameliorate the history of our forebears –– also require care for our audiences and a significant measure of self-care.” In the spirit of self-care, the plainspoken yet evocative insights in her 2022 guide Am I Autistic? invite readers to consider recognizing and celebrating themselves as autistic, if it feels appropriate, and to weigh the possibility of getting a formal diagnosis. And for her ambitious 2023 text Neuro Photo Therapy: Playfully Unmasking Through Photography & Collage, based on an autistic art-making focus group project and including images and written contributions from collaborators, Boué lays out a personalized approach for neurodivergent readers, particularly those diagnosed or self-diagnosed in adulthood. Her goal is to reinforce pride and confidence in neurodivergent self-recognition through responding to childhood memories through collage methods and self-portrait photography, operating both alone and in community.

Safe as Houses, photographic series, 2020.

Safe as Houses, photographic series, 2020.

John Stezaker, another British artist and archivist whose simple split and human-object hybrid portraits bear a pointed similarity to many of Boué’s collages, once observed:

In a way, I see my work divided into two roles, the collector, and collagist… (M)y practice (was) actually…

the reverse of working from the archive: it was working towards the archive. My collecting of images is a

sort of end point that is static, whereas the collage work tends to be an exploration of images through the

process of cutting or fragmenting in one way or another. So the collage work is a fluid process involving a

multitude of images – whereas collecting involves finding what remains, is finite and fixed.

This action of collecting as slow discovery is not a process of whimsically appropriating, cleverly reframing, and freely transforming history with collage, but carefully attending to minutiae within an archive of images, in order to interpret the present through contemplating an inaccessible but mesmerizing past. This dynamic tension of “working towards the archive” marks the way in which Boué approaches her father’s life story, as well as how she worked with her collaborators and her prospective readers in the Neuro Photo Therapy guidebook, “work(ing) to support a process of unmasking following a late discovery of autism/ND.” “You may need to pace out the process of gathering the image sources you choose to work with,” Boué writes. “Spend as much time as you like! This stage of the work can be immersive and even rapturous, as you spend time gazing at your primary sources - whatever they may be.”

A brief note about masking, Analogue collage, 2023. Thinking aloud. Photograph, 2021.

Through the gentle, self-paced suggestions that she offers, photographs can operate not merely as representations and documents of the past, but objects in the present that can work like a mirror, offering a stable place from which to begin constructing and revising a new apprehension of identity. Similarly, Boué’s reflections on her father move these meditations on memory into the challenging realms of both small-scale relationships and big-picture politics. In her reflections on D.W. Winnicott’s writing during the war, Joyce Slochower detects the seeds of a statement he would make in 1969 that amply resonates with Boué’s understanding of not only the potential but the larger purpose of art: “If only we can wait, the patient arrives at understanding creatively and with immense joy (.)”

Mona Lisa (after Duchamp). Photograph, 2022.

Comments