Chloe Pascal Crawford: Works in progress

- Bert Stabler

- Nov 9, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2023

Text by Bert Stabler

Upon viewing Chloe Pascal Crawford’s three-channel video Upright Nationalism, without thinking too hard about the title, it could easily be read as a trailer for an inspirational patriotic documentary about disabled veterans, or a promotional video for the Veterans Administration. In the video, a montage of men and women who have been outfitted with exoskeletons, biomedical technology designed to permit those without orthopedic mobility in their legs to stand and walk, rise to their artificial feet and take their first hesitant steps—all accompanied by the rousing strains of “The Stars and Stripes Forever.” Through cross-cutting between clips, an array of different people, primarily in various ceremonial settings, push away their wheelchairs and are strapped into exoskeletons (with some lingering attention to women’s breasts), and begin to brace their arms. Then this array of people push off of their wheelchair armrests and start to walk, with the aid of crutches, braces, and walkers. These scenes are juxtaposed with real and virtual military training scenarios, and we see audiences of helpers, loved ones, bystanders, and political leaders react with amazement, joy, and reverence as these once-damaged but reborn heroes tentatively emerge (or re-emerge) as ambulatory cyborg butterflies from a figurative cocoon of all-too-human compromised mobility. Were it not already taken, an apt title might have been Triumph of the Will.

Chloe Pascal Crawford, GonnaFundMe (I Need a New Wheelchair), ongoing

The subtle but sharp critical tone of Upright Nationalism is betrayed within the video only by the cutting and multiplication of clips, which underscores the sense of a crafted and rehearsed narrative of reanimation. But the stakes of the work are made plain in Crawford’s project GonnaFundMe (I Need a New Wheelchair), an equally grim but somewhat more apparent, and significantly more personal, satire of crowdfunding campaigns launched to pay medical expenses. Crawford actually does need a new wheelchair—a newer and more comfortable, but still completely manual device—nothing as advanced as a power chair, let alone an exoskeleton. She is several years past due for a new one, and yet all she has gotten from her insurance company is a series of delays and evasions. In conversation with me, Crawford emphasized that we have not entered a new era in which medical technology is overcoming once-debilitating impairments. Rather, the vast majority of disabled people continue to inhabit a world of perverse Kafkaesque austerity, in which essential supports for basic everyday function are perpetually promised and repeatedly withheld.

Like Upright Nationalism, the site-specific 2021 piece For the 12 Disabled People in Lebenshilfe Haus (Area of Refuge), made for the Crip Time group exhibition at the Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK) in Frankfurt, Germany, has a superficial sheen of health and happiness. In a brightly-lit, white-walled stairwell within the museum, an area of bright blue paint reaches from the floor to slightly below the first handrail a visitor encounters, bringing to mind a hallway leading to a community pool. The flowing contour where blue meets white continues at roughly the same height as the stairs go downward, and the implied water gets deeper, rising above the eye level of most standing adults. As it happens, the water represents a recent flood that, as the title suggests, killed twelve disabled people in a German residential institution in Sinzig, Germany in July 2021. The victims were trapped in an area that was only accessible by stairs. As a wheelchair user herself, Crawford could not navigate the stairwell in the MMK, but had the wall painted to her specifications, as well as having a convex mirror installed that allowed anyone at the top of the stairs, but particularly someone at the height of a seated person in a wheelchair, to see around the corner to the end of the hall.

The lack of a viable evacuation plan that considers disabled people (let alone informed in consultation with disabled people), underscoring the disposability of disabled people’s lives, has been a theme that Crawford has focused on in other works. Her MFA installation, Buddy System, was another example of Crawford’s light conceptualist touch. It was inspired by her outrage upon learning that the emergency plan for the building that housed her studio at Rutgers University only made provision for vulnerable people by recommending an informal “buddy system,” in which the posted plan suggested that users of building spaces designate and promise to check in with a chosen “buddy” in case of a hazardous event. Crawford created and posted a much-improved emergency plan that considered the needs of various disabled people, and posted it on a bulletin board in the gallery. Echoing this labor of editing, and inspired in part by feminist conceptual artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ concept of “maintenance art,” the sparse exhibition also included a significant amount of “invisible” work, wherein Crawford cleaned the floor and patched and repainted the surface of the gallery walls, to the height that she was able to reach while seated in her wheelchair. As seen above, Crawford has recently been working in a similar vein on extensive disability-focused revisions to the hurricane emergency instructions issued by the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, a project tentatively titled Hurricane Guide. Along with new hypothetical disability-focused emergency instructions, the image features icons of a wheelchair user and a person with a companion animal rushing toward a set of stairs, marked "Hurricane Evacuation Route," stairs which will presumably not be accessible to the wheelchair user.

Chloe Pascal Crawford, Hurricane Guide, ongoing

While Upright Nationalism and Area of Refuge focus on identifying a problem, and Buddy System and Hurricane Guide offer explicit solutions, a didactic, even pedagogical aesthetic is apparent throughout Crawford’s work that operates on the expository maxim, “show, don’t tell.” But despite having a clear political vision, Crawford does not perceive her artwork as a direct mode of struggle. Beneath its surface of unambiguous signification, my conversation with Crawford helped me to understand that her work rests conceptually on sets of contradictions that are not easily resolved.

Relating to this issue of efficacy and direct action, the first tension I notice is the one between performance and function. Crawford described the multiplied ceremonial scenes featuring triumphant exoskeleton users in Upright Nationalism as “a performance of uprightness.” She went on to talk not only about the unattainable cost of exoskeletons for nearly all wheelchair users, but also their ineffectiveness as mobility aids, as exoskeletons have not been engineered to climb steps, but rather for the military application of carrying loads over uneven terrain. For the military, she says, “the recruitment numbers are way down,” which incentivizes the further exploitation of already vulnerable groups. This aspect of empty performance as opposed to substance is also front and center in woefully insufficient evacuation plans like the ones Crawford addresses in Buddy System and Hurricane Guide. But while she strongly endorses the leadership of disabled people in crisis planning, Crawford also sees her own role as an individual artist as one of semi-satirical representation rather than proactive intervention. If she were making a hurricane response guide, she says, “you would actually make a different product… that wouldn’t resemble what they made.”

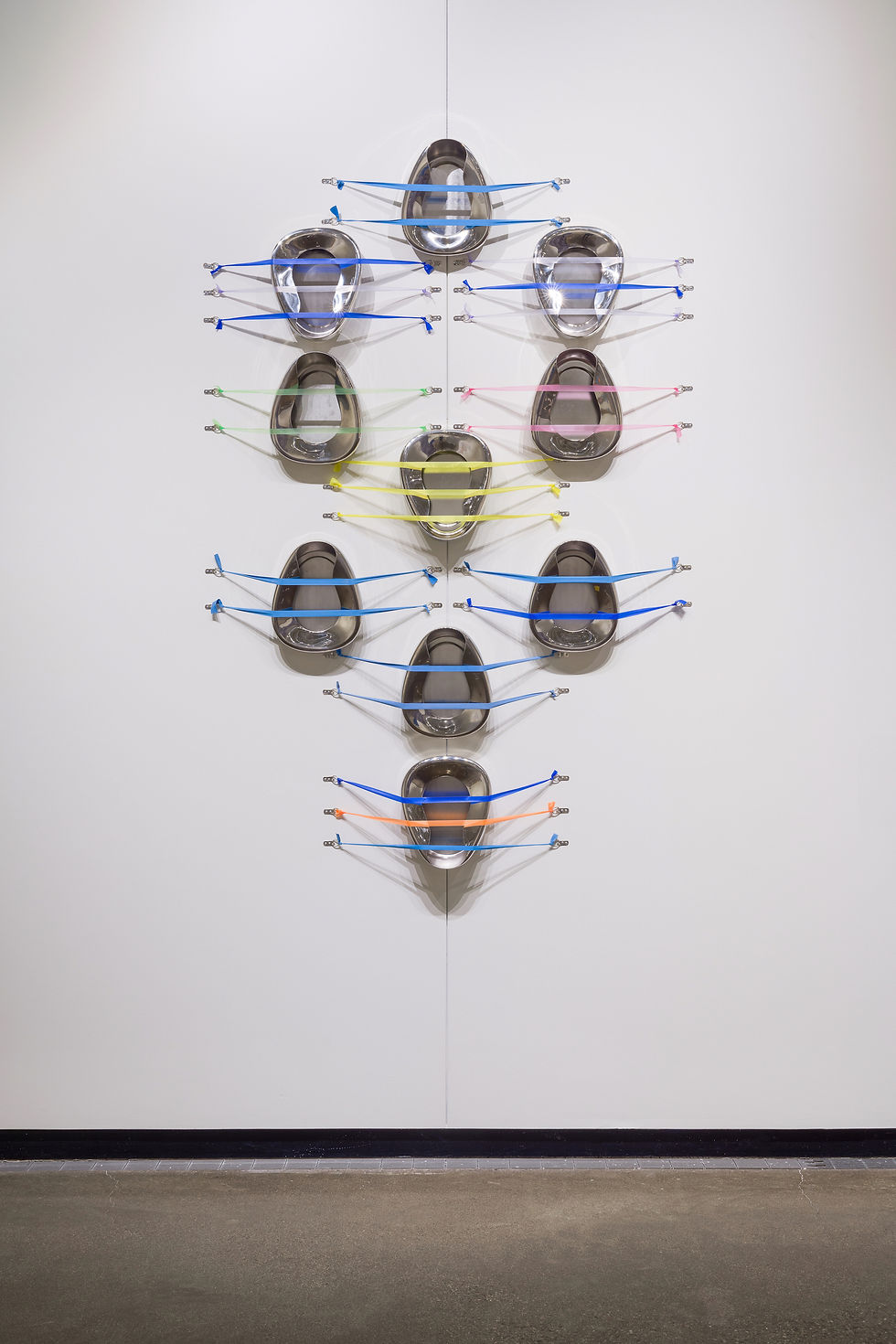

Chloe Pascal Crawford, Rehab Pay$, ongoing

A closely related theme in Crawford’s work is the disparity between labor and payment. An artifact she has been contemplating is the standard envelope that she regularly receives from the state of New Jersey, which has for years stated “Rehabilitation Pay$.” The irony, as she notes, is that her rehabilitation continually fails to pay her, but it certainly pays insurers and medical manufacturers. She also shared two letters from one envelope, from the same medical provider; one addresses her as a “patient,” and the other as a “client.” But as she says, “I’m not really the client.” Ultimately, rather, “the insurance is the client.” Her painting and patching work in Buddy System drew on ideas of invisible labor from Ukeles’ Maintenance Art Manifesto, which echoes the ongoing unpaid work she has had to undertake in order to get a new wheelchair in I Need a New Wheelchair (the patience of a patient), which in turn serves as a counterpoint to the prohibitive cost and functional irrelevance of the exoskeletons in Upright Nationalism. Thus, her utilitarian anti-aesthetic speaks directly to her diagnosis of the way in which funding is allocated based on superficial appeals to influential interests, rather than to the everyday survival needs of people who are considered economically unproductive and thus disposable.

Chloe Pascal Crawford, Dear Client/Patient, ongoing

Last but not least in these dichotomies of appearance and reality is the essential divide between disabled people and their caregivers, the former commonly assumed to be undeserving burdens on the latter. The inconvenience and expense of having adequate safety measures and/or calling in necessary staff during a flood at the Lebenshilfe Haus resulted in the twelve deaths commemorated in Area of Refuge. More subtly, Crawford pointed out in our conversation how emergency instructions, to the extent they even consider disabled people, reliably and reflexively address able-bodied helpers rather than disabled people requiring specialized information and assistance; in her words, “they all fall into the trap of talking to the person who would be helping the disabled person.” Commenting on the plan she critiqued in Buddy System, Crawford remarked, “the buddy is not physically supposed to help or do anything except just tell someone where you are.” She intentionally shifts this perspective in Buddy System and Hurricane Guide, speaking directly to as wide a range of specific impairments as possible.

Crawford’s art ultimately confronts problematic assumptions underlying distinctions between functional and nonfunctional art: art undertaken either for the market and/or social uplift, in contradistinction to art for art’s sake. Implicitly shared definitions regarding functionality leave untouched any questions about what or who is and isn’t considered functional, and who or what a functional object, idea, or institution is intended to serve. Grounded in material need, analysis, and labor, Crawford’s work provides a powerful and embodied argument for critical disablement as a necessary element in both aesthetic reflection and political action.

Comments