Christopher Samuel: Institutional Model

- Bert Stabler

- Mar 16, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Sep 12, 2022

Christopher Samuel is a disabled British artist whose work has been crucial for me in articulating my idea of an "institutional model" of disability. Specifically for this blog, as well as for my art education students, he has created these three informational videos that articulate the relationship of disability to institutions of education, employment, and funding, with attention to the U.K. context. Chris makes ample use of archival footage, with narrators and caregivers using distinctly outdated terms and concepts to discuss the experiences of disabled people. By contrast, many of these disabled people, when they are given time to speak, articulate relatively timeless and universal aspirations. In so doing, he emphasizes the gulf between those two groups of speakers, and thereby presents the long and still-incomplete process of moving from actively violent banishment, warehousing, suppression, punishment and neglect, toward a goal of recognizing, affirming, and incorporating people with every kind of disability as fully interdependent members of society.

My art education class was fortunate to have Chris as a recent guest speaker, and he spoke eloquently about his artwork, which has for years been lyrically and unflinchingly exposing, documenting, and critiquing the bureaucratic, medical, and physical apparatuses of ableism, and those who are harmed by those apparatuses. After his visit I asked two follow-up questions in an email, the first of which he helpfully paraphrased as "How does it feel to have to fight against - essentially - the hand that is feeding you?" "When I really discovered the social model of disability," Chris says, "I realised I had rights, and that certain things weren't acceptable. I have to fight for the things I get, but equally I'm scared of loosing the (means-tested) care that I have got. But more damage is done, long term, by not having the right care. Me not having autonomy over my care is one thing that is worth fighting for, because that being right or wrong affects so much else in my life. We are bought up to not moan or complain, especially as disabled people. But I am willing to compromise & not be comfortable. Temporary discomfort drives me, to make things better in the end."

My second question he restated as being "about disabled people (secretly) wanting to be more 'normal.'" On this point, Chris said: "I don't know that that mindset of wanting to be 'normal' in body/mind is exclusive to disabled people. And that mindset can still exist within the social model - which just asks for equality of access/opportunities - working with the reality of how a person actually is. Everybody wants society to accommodate them, and to have an easy existence. And if you are 'average' then society does. But as you move away from 'average' (and become a smaller & smaller minority of the population) the adjustments you need start to look more radical - But if half the population used wheelchairs, then ramps, lifts, accessible doors etc, would be the norm, and nobody would question the need for them."

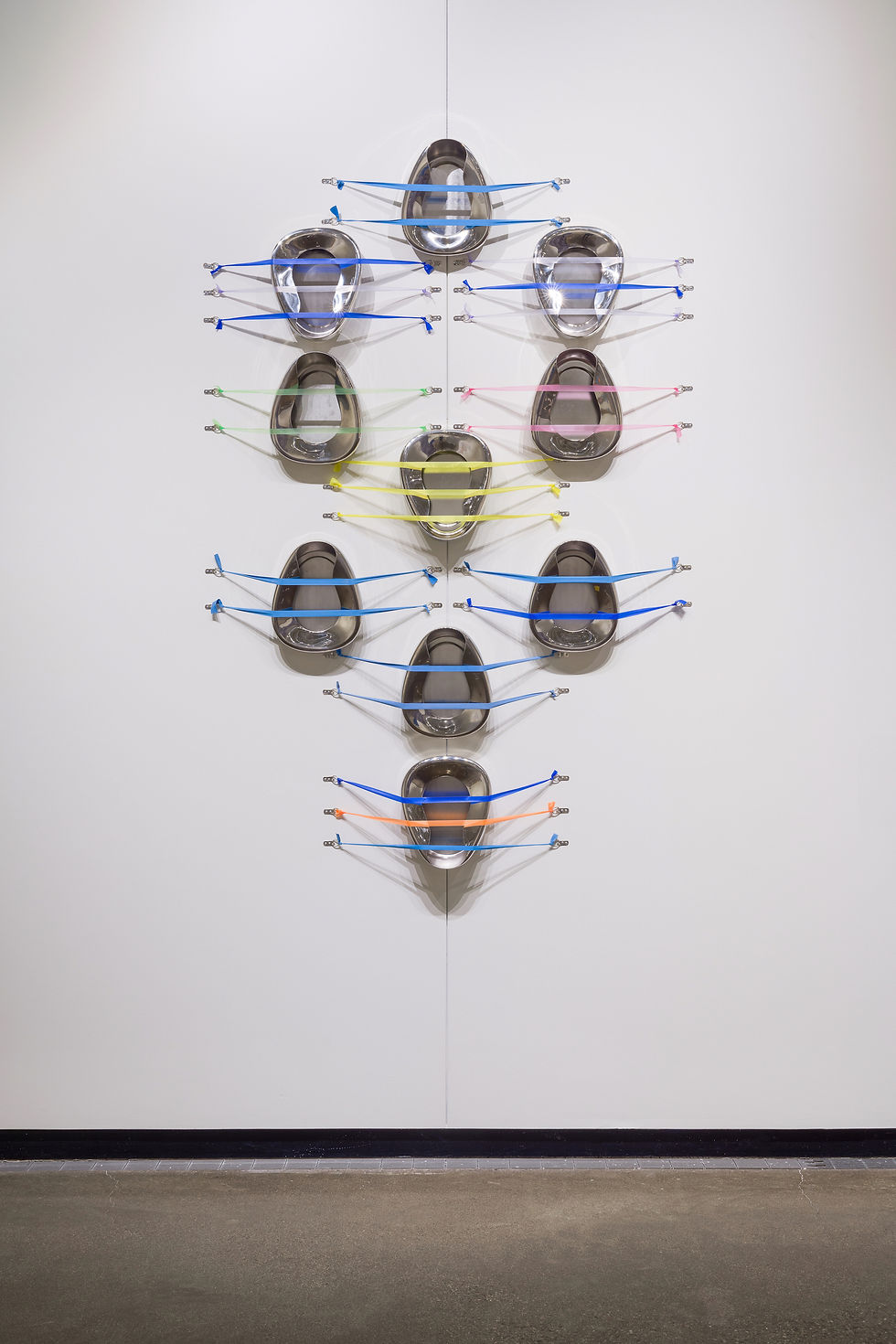

Chris has a form of muscular dystrophy, and he has made a range of works that plainly chronicle his experience as a wheelchair user, being forced into institutional settings early in life and attempting as an adult to navigate the physical environment, the environment of government and medical service providers, and his own domestic environment. He was made homeless immediately before graduating from college, and in response to this experience Chris made creatively redacted print works based on his correspondence with public agencies, and he designed a hotel room to reproduce for able-bodied hotel guests some small taste of the difficulties he encountered while living in an inaccessible hotel room. He has applied similar creative redaction to interviews with other disabled people, and has invented domestic care worker reports that reflect his own experiences of being denied agency in his own living space. He is currently developing work based on research in medical archives. Being a working-class disabled artist of color, Chris can easily draw from his daily life to illustrate multiple forms of exclusion, in terms that are practical, personal, and direct.

Chris's work offers a clear inspiration for the "institutional model," a term based on both straddling and circumventing the ideas of the "medical model" and the "social model" of disability. Along with his mother, he has spent his life fighting against social norms, while simultaneously working to get needed medical support. In addressing my art teacher education students, he spoke about the need for teachers to spend time both listening and being responsive to the needs of disabled students, while also preparing them for adult life among non-disabled people in ableist environments. In the specificity and clarity of his work, Chris disseminates information without being patronizing, esoteric, or shrill, in order to look back, as he says, at the "medical gaze" that has attempted to define the parameters of his life.

-- Bert Stabler

Comments