Cielo Saucedo / Body double

- Bert Stabler

- Jan 21, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Feb 3, 2024

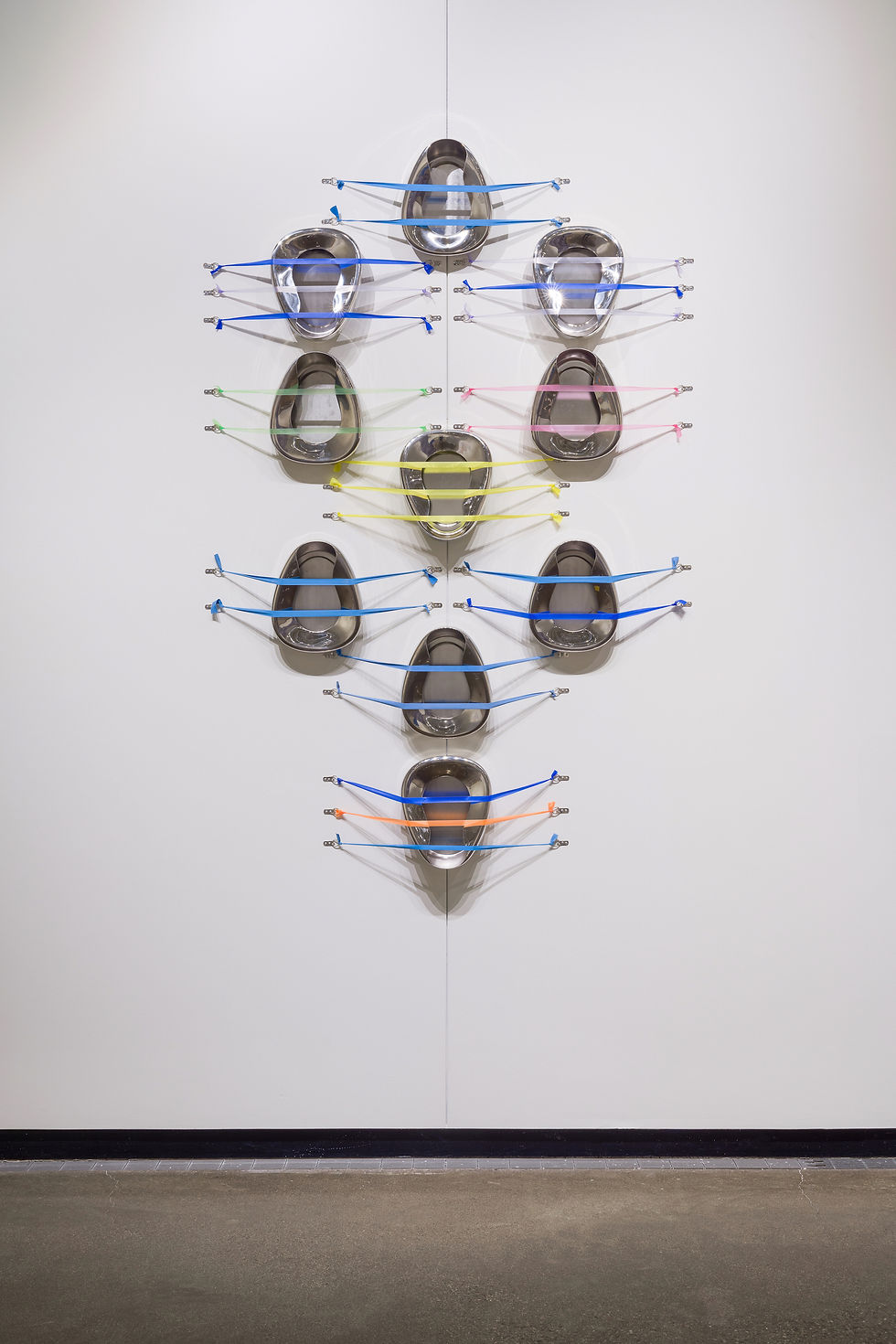

Cielo Saucedo, Sublux (low angle)

Cielo Saucedo’s recent sculpture Sublux, an image of which they posted on Instagram with a list of materials, is a cracked and weathered rendition of a human foot made from “Maseca, LA tap water, self tanner, Nescafe.” Shot from a low angle in forced perspective against a blank white background, the enigmatic object is indeterminate in scale. It could suggest a towering foot-shaped mesa in the Sonoran desert, miraculously carved by wind over millennia. While evoking stratified earth in an open pit mine, the texture is at the same time unearthly, evoking the velvety surface of a microorganism imaged by a powerful microscope, and hinting at an equally miraculous phenomenon of parallel evolution. A point of art-historical comparison might be Paul Thek’s Technological Reliquaries; this was a series of wax limbs and amorphous meat-like hunks and scraps individually encased in vitrines that Thek bedecked in alluring coverings such as resin, nylon, and butterfly wings, evoking the mundane, repellent, clinical, and holy resonances that surrealist sculpture inherited from auratic Catholic ephemera.

That being said, it also might not be hard to believe that the image was simply digitally fabricated-- which, in a sense, it was. Saucedo’s training is in digital 3D animation, and their approach to representing disability is based in a philosophically-informed notion of the virtual. As they told me, “impairment is actually built into the virtual through glitches and viruses .” But it turns out that Sublux is far from ephemeral. Rather, its materiality is both integral and multivalent. They made it using a 3D printer they built from a design ceramicists use for printing in clay, but modified it to extrude their own recipe of symbolically laden slurry. All the materials are references to the cultural politics of Mexico, with the self-tanner and Nescafe hinting at the national racial idealization of mestizaje, the mixture of Indigenous and European bloodlines in the dominant Mexican population.

Sublux (high angle)

Perhaps most significant, however, is the Maseca. Maseca is the leading Mexican brand of corn flour, used primarily in making tortillas. Corn flour production finds its roots in the inherited Indigenous practice of nixtamalization, in which corn is processed through cooking and soaking in lime. However, Saucedo explained that sourcing of corn for the manufacturing of Maseca has long been supported by government subsidies, which moved away from small peasant farmers to large-scale producers, coinciding with a period of drought that devastated Mexican agriculture and disrupted national food systems. At the time of this drought in the 1940s, the U.S. began allowing in large numbers of low-wage migrant farm workers. This decades-long initiative, known as the Bracero program, brought Saucedo’s parents to the United States. With the advent of NAFTA, they went on, Maseca is now made primarily from transgenic corn produced in the U.S. At this point, they told me, “the biggest export that Mexico has changed from corn into labor.”

Sublux is in fact based on a scan of the artist’s own foot, and Saucedo notes that the cracks that have organically appeared in the 3D print match up with areas of pain in their own feet, as a symptom of their inherited connective tissue disorder. Connecting this to the history of Maseca, they describe the influx of Mexican laborers under the Bracero program as a “mass disabling event,” akin to the current COVID pandemic. This is due to the brutal conditions faced by agricultural workers, particularly in terms of their exposure to hazardous chemicals and ergonomically disabling tools and practices.

Maseca Crate (exhibition shot, work in foreground)

Maseca Crate (detail shots)

The sculpture is also an extension of an ongoing series of Maseca-based prints of Mesoamerican artifacts, made with the idea in mind that “artifacts are proxy bodies of Indigenous folks,” but with museums ironically “pouring more resources into the suspension of these objects than the actual lives of the indigenous people from which they stole the objects.” This institutional preservation of trophies, which Saucedo analogizes to an emergent medicalized rhetoric of “care” in curatorial discourse since the advent of the pandemic, is epitomized in the plywood and Styrofoam in which museums store and ship their prized possessions. Vaguely evoking the animal-shaped and anthropomorphic figurines and vessels of classical indigenous civilizations, the crumbling and rotting forms of the Maseca prints are cushioned, supported, and framed by the normally invisible logistics of museum operations, de-neutralizing the ongoing extractive colonial history through which such items became objects of display.

Score for Perpetuity (detail shots). Wooden crate, cut foam, silk ribbons, silk pillow.

One natural outcome of putting their own body in the place of these artifacts, then, was to create a shipping crate custom-built to their corporeal dimensions, part of a piece entitled Score for Perpetuity. Saucedo’s performance with this work, entitled Absence!!!!!! evokes Robert Morris’s 1961 work Untitled (Box for Standing), but it lies flat on the ground and contains a foam bed, carved to fit their body and outfitted with silk straps and a silk pillow, as well as assorted provisions and medications to sustain them during a multi-hour performance of being sealed in the crate. When this performance took place in November, at Saucedo’s MFA preview show at UCLA, visitors banged on the crate, tried to talk to Saucedo, and peeled stickers off the outside as souvenirs. This performance could also conjure Chris Burden’s Five Day Locker Piece, or Santiago Sierra’s installations in which workers are remunerated for remaining inside cardboard boxes for the length of a day. However, as the title implies, the artist was not present—which could be considered a repudiation of Marina Abranovic, and other canonical performance artists renowned for their endurance-based work (perhaps another apt comparison would be the tomb of the risen Christ?). They said, “It wasn't that uncomfortable because I've done so many MRIs in my life… I thought, oh, I can do this for a while..” But, “I want to push against that sort of durational performance that qualifies what is expected of a performer”. “Because…,” they concluded, “as disabled people, we already live through endurance performances, you know, it's constant.”

Score for Perpetuity (POV detail shot of Saucedo's body in the crate)

The virtual supplement for their absent body, however, along with the presence of Saucedo’s collaborator Carlos Agredano, was the score for the piece, on display during the performance. “The performance was performing with or without me there… the score was there, and the documentation of my body inside of it, which… stages the performance and itself is framed as a demonstrative act that both implies a future action while tossing forward that action to a distant present.” Echoing examples from the history of Fluxus and Conceptual Art, the score spelled out every step of Agredano’s skilled construction of the crate. And effectively, as Saucedo suggested, the score defined and activated the piece, irrespective of the artist’s physical presence.

Score for Perpetuity (detail shot of images and written score)

This conceptualist interest in the signifying functionality of the contract is key to the political poetics of Saucedo’s work. Their piece Access Rider is an informal one-page agreement that they ask people to sign when visiting their studio (although they realized during our interview that they had neglected to ask me to sign it before our Zoom session). The rider sets expectations for permitting food and drink, as well as allowing limits on time and noise, but it also states the economic stakes of the interaction and attempts to make power dynamics more transparent. A number of signed copies can be seen on their website, but Saucedo told me that some prospective visitors had refused to sign the document, while others had simply ignored the request. They are working on a new version of the rider which focuses on the parties’ needs—again, defined in opposition to widely overused notions of institutionalized “care”.

Access Rider (image from series)

Similarly, in an article which is simultaneously a proposal (recently approved for funding by Eyebeam), Cripping_Conputer_Graphics: Perspectives on disability representation in CG via community generated asset library, co-written with Nat Decker, they include a section they term a “bespoke terms of use,” in which the archiving of disabled avatars for use in games and animations is undertaken on the terms of disabled creators. In comparison to the ways in which non-normative online representations of bodies and movement have traditionally been exploited, Saucedo and Decker seek to give creators the space to decide how the images they generate are deployed. Disabled bodies are often seen as evil and monstrous, as well as desexualized or hypersexualized, qualities which Decker and Saucedo don’t necessarily object to intrinsically. “I think people should be able to choose if they do want to engage with (monstrosity) discourse or if they don't,” said Saucedo, “or if people want to be sexual beings online, or maybe they want to be paid for their work, or for their movement, or maybe they only want their friends to use their image.” Saucedo and Decker are now planning to consult with a lawyer in order to figure out how binding they intend to make their terms of use. “Essentially what we're doing,” they told me, “is trying to create the conditions for disabled people to have their bodies in the virtual in a way that they feel. It’s mostly somatic, really.”

Keep Moving Forward (detail), video game hosted on Unity, two levels

Saucedo describes initially being trained as an animator, before coming to graduate school, where they “really wanted to make the virtual actual.” They now see their creative purpose less in imaging a utopian future, but rather in describing the specific context of the present, the circumstances from and through which transformation must be brought about. In witnessing the responses some people had to their access rider, they realized that “a naming of the conditions which we live under feels too radical for some people.” Along with a full-body Maseca print of their body, they are planning a machine vision project for their thesis show, in which attendees will be able to witness a visual and vocal ticker outside the gallery that describes how the exhibition is experienced by algorithms trained on a curated set of images. In pushing the limits of captioning as mechanized ekphrasis, Saucedo questions the linguistic focus of much conceptual disability art, while also undermining the colonial presumptions of translation. With the disavowal implicit in practices of formal recognition, they contend, institutions, including galleries and museums, continue to substitute mechanisms of care for the provision of needs.

Comments