Disabled Artists Symposium, 4/10/24

- Bert Stabler

- Jun 2, 2024

- 54 min read

Updated: Jun 5, 2024

Ariella Granados, still from Untitled Self Portrait, 2019

This was a recorded panel featuring six disabled artists, held on Zoom and at Illinois State University's Multicultural Center, in April 2024. The featured artists included Cielo Saucedo, Darrin Martin, Mae Howard, Joselia Hughes, Dominic Quagliozzi, and Ariella Granados. The panel was moderated by Bert Stabler, and these artists were all featured on this disability art blog, Institutional Model. The transcript is posted below.

Bert Stabler: Hi, everyone. It's noon, and we're going to get started. Of course people can come and go as they please, either from the Zoom, or from the actual IRL room that we're in. Welcome to our third annual disability or disabled artist symposium-- I think I've renamed it a couple of times. My name is Bert Stabler, and I'm going to tell you a little bit about the event, and read our acknowledgments and get quickly to the artists who are here to share their work with us, and tell you more about them in their own words. For starters, I want to tell you who's gonna be speaking today, not necessarily in this order. Our artists today are Cielo Saucedo, Joselia Hughes, Dominic Quagliozzi, Ariella Granados, Darrin Martin, and Mae Howard. I don't know if we ended up getting ASL interpretation-- there was some confusion around that. And I'm very apologetic if anyone was expecting that. And it's not currently happening. If it is happening, of course, please pin it, and you can make use of it. I want to thank first of all our sponsors for this event. There are many here on campus at ISU. I'm really thrilled about that. And we want to think first of all, the Multicultural Center, which is where we're sitting. They're providing food and space today, as well as technical support for this event to happen. They have a really nice room where you can see the audience and hear the audience when it comes time for discussion, which is really cool. I'm very happy to work with them for the third time on this project. We wanna thank again the Women's Gender and Sexuality Studies Program. I left their name out in an email, and I wanted to express contrition again, and thank them very much. I wanna thank both the Wonsook Kim School of Art, which is where I'm based in art education. as well as the Wonsook Kim College of Fine Arts. I want to thank the Student Access and Accommodations Office here at ISU, the Queer Coalition, the Latin American and Latino/a Program, the Office of the President of ISU, as well as the Department of Special Education at ISU. So yeah, we have a lot of great supporters for this event. I'm gonna move on to a few words of acknowledgement. The Wonsook Kim School of Art, which is where I'm based, not currently where we are in the Multicultural Center, but same campus, the Wonsook Kim School of Art acknowledges the African diaspora violently robbed of life, labor, land, safety, community, culture, and dignity, during and after slavery. We also acknowledge those violently robbed of life, labor, land, safety, community, culture, and dignity through sexuality, gender, race, wealth, language, and ability hierarchies. These hierarchies are and have been sustained by a range of power formations, including the state. The Wonsook Kim School of Art acknowledges the Illinois State University, the Center for the Visual Arts, and the Multicultural Center here, all we do takes place in the land of multiple native nations. These lands were once home to the Illini, the Peoria, the Myaamia, and later, due to colonial encroachment and displacement, to the Fox, Potawatomi, Sauk, Shawnee, Winnebago, Ioway, Mascoutin, Piankashaw, Wea, and Kickapoo nations. We strive to honor the ongoing legacies of these and other indigenous peoples who may have been excluded in this acknowledgement due to historical inaccuracies and erasure. And I also have an addition that I want to acknowledge that acknowledgements such as these are necessary but also insufficient. I'm also gonna, on the context of labor, shout out our new faculty union, which is bargaining as we speak. Quick introduction to me. My name is Bert Stabler, I'm an assistant professor in art education. I'm a nearsighted, neurodivergent, cis white man. And that's probably enough description. I'm wearing a mask, so I might sound funny. So I'm gonna jump in, and I think I see that all of our artists are on the call, they should be able to share their screens. The artists will be presenting their work in whatever way they choose for 5 to 7 minutes apiece, which hopefully will give us some time to have discussion, some Q & A, some comments after they're done. So I was just gonna choose Ariella to go first. Ariella, does that sound okay? So I'm going to read. I'm going to read Ariella’s bio. Ariella Granados is a multidisciplinary artist, based in Chicago, Illinois, whose work utilizes video, sound, costuming, makeup and sculpture to explore the liminal space between fiction and truth. Their work integrates green as a signifier of rendering the disabled body against the complexity of the sociopolitical landscape. Granados's work is intertwined with the consumer's inability to not be fully satisfied with the consumption of commodities. Utilizing dynamic, world-building techniques, they critique the body as a commodity itself, offering her own lived experience as a bicultural person through their work, Granados invites the viewer into a world where they must confront questions of agency and authenticity. Granados holds a BFA from the University of Illinois at Chicago. They are a current 3Arts Bodies of Work Residency artist, and an inaugural artist in residence with DCASE, that's the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, and the Mayor's Office for People with Disabilities. Ariella, you have the floor.

Ariella Granados: Hi, everybody, My name is Ariella. My pronouns, are they/she, and I'm gonna share my screen with you all real quick. If you can see this.

Bert: Yeah.

Ariella: Okay, cool. So my name is Ariella, I am a Chicago based artist, and as Bert mentioned, I am a multidisciplinary artist working through performance, video, sculpture and costuming. So I'm just gonna kind of take you through the beginning of my practice to where I currently am. So when I was an undergrad, my thesis was a project called “We Used to Have Cable Before You Left,” and in that project I used green screen as a way to situate my body in different domestic scenes. Which at the time was referencing personal histories and narratives. So in one of these videos, I dressed up as like a news interviewer, and I created 2 characters that would display the interaction between a mom and a daughter, and I did that through the dramatization of a single mother's narrative in the fashion of Latinx media tropes. So for this video, I was using something very popular in Mexican television called Univisión. So it was, you know, playing with tropes of satire and sarcasm while still at the time, trying to just process and understand my lived experience as a first generation person. And then this was another project that I made, called “Bodies in Progress.” And so this was a series of work that was fake advertisements where I was interrogating the possibility of a disabled body becoming a commodity similar to conventional mainstream bodies and present media. And so it was the desire, repulsion of the presence of a disabled body in the media. And through this I question the intention of representation through the media. Is it really for the sake of representation, or does it just operate as another capitalist tool to create false desire and empathy? So these are some of the images that I had made. I was drawing inspiration from things that were familiar to me. So I grew up very close to something called Herbalife, which is a dietary supplement. Growing up in Texas, Christianity and religion were something that were very close to me at the time, so I thought it'd be humorous to kinda put a twist on it, and that was another one. This one was called “Inglés Sin Barreras”. So it was like an English language learning program that was advertised in the early 2000s. And then after that, I created a series called “1 800 Inaccessible,” which was a video performance where I superimposed my labor with the audio sound of this advertisement, stating how this product, being knives, could be used with anyone by anyone, which was false. So here I'm critiquing the inaccessibility of domesticity. And after that I then did a performance called “Eating with Desire,” which is a performance that uses consumerist objects, such as food, along with theatrical props, such as the red lipstick and the gloves, to create a more sensual environment. And in this performance I attempt to open food items to the best of my ability, and in this case it was with my hand and my mouth, and I then proceeded to eat the items. And here I'm interrogating the politics of desirability and sexualization, and through this performance I was reclaiming narratives that don't represent disabled people, as inherently sexual beings. And so, moving on, after that I started then, still playing with ideas of green screen and creating environments where I could just reimagine things. And my mom got COVID in 2020 and has now been dealing with long COVID, so I made this through the pandemic just like trying to process everything that was happening at the time. And this is when I think I started to become more interested in moving away from green screening myself into existing images, but then creating my own environments. And so I moved away from using green as a way to insert myself in space, and I then became interested in using the color green as a signifier of rendering my body-- the color green is oftentimes used as a way to render space, and so I became interested in using the color green as a way to render my body. And so this is one of the first times that I ever that I used green on my body, and it was the performance. (Playing video) “It's my favorite. We call it intergenerational trauma. I'm just gonna lightly apply this all over my face, working my way from my nose around my cheeks, down to my chin, and up and around again.” (New character) “My name is Maria. I'm 28 years old, and I just immigrated from Monelitos. I came here with my mother and my sisters, you know, in search of a better life. I will say, it's been a bit difficult, adjusting to a new language in a new culture. And of course oftentimes being a bit unemotionally available to my offspring. But nonetheless, I'm her mother. She is my daughter. And we are one.” So that was when I began exploring Green on the body. And so I continued, in the next few years I then became interested in really exploring disability and my relationship to disability. And so this was a performance I did in Joshua Tree, where I had a green, large piece of fabric, and I was trying to stretch it out to the best of my ability, and I then would green screen video work which was like a journal entry of me, just expressing my experience and finally having the language to even think about disability and what that meant, and how I wanted to explore those themes in my practice. After that I then continued again, and this was another video where I began to paint my arm green. So this was a sketch I did during the pandemic. I painted my arm green, and I green screened it with static, and that felt representative of what it felt like for me to live with chronic pain. After that I did a residency in Mexico, in Puebla, where I did a performance in front of a Catholic church, and I painted my arm blue and green and kind of just walked around the city just to see what the public's impression would be. And this is just more work that I did while I was in Mexico. This one was called “Labor, Like my Mother’s”. And it's just a video that's playing homage to ritual, and also recognizing the importance of ritual, and also understanding that the way my mom, you know, performed rituals, such as like cleaning or attending to the home, looks different from how I do it. After that I then began to incorporate more elements of theatrics and costume, and so in this case I did another iteration of painting my arm, and that being representative of rendering my body with, you know, chroma blue or chroma green, is me changing my body or me fixing my body. And so in this performance I dressed up as a hospital patient, and had a person dressed up as a nurse, and so the act of them painting my arm was them healing me or curing me. And then, after that, I think I just was able to really evolve the character more. I designed this arm that I knitted. And I then begin to explore this character in more music spaces. And so I was performing with this character and I made a video to that as well, where it's like a 20 minute improvisational jazz piece, that's kind of just exploring themes of identity, family being first generation, and so forth. After that I did a project called “Disabling Utopia”, where I made an open call to people of the community, and I casted 9 to 10 people with disabilities, and through this project they were able to design and think, design their own miniature dioramas that we would then green screen them in, and we together help them design alter ego characters. And so I style-directed, and did the makeup for these, and they made their boxes, and so these are just some of the screenshots from the interview video. And this was from the workshop. These are the boxes that we made, and then these are the final images. And so you know, the project that I most recently finished is called “Chroma Key After Me”, and it's the more personal iteration of “Disabling Utopia”, where I recreated my childhood home through ceramics. So I made every room in the house, and I'm reimagining what that house is like. And so I'm still in progress with this project. But I have finished the ceramic portion, and after that I'm gonna green screen myself into it and reenact and reimagine memories of childhood. So these are some of the sketches from before, and then these are some of the rooms, and that is all.

Bert: Wonderful. Thank you. That was really great, and we will just kind of keep rolling along. But please, everybody kind of make note of questions you had, or observations you had about Ariella's piece. I think my volume is controlling that volume, so I'm not gonna turn it down, even though I'm echoing a bit. Thank you again, Ariella, and we will certainly return to you in the Q&A. One thing I didn't mention is that all the artists who are presenting themselves today were interviewed on and profiled on my blog, which is called Institutional Model. It focuses on conceptual art related to disability, contemporary artists who are disabled and make work about it. You can find it at bit.ly/institutional-model, and you can kind of see some other things that happened in the conversations and my reflections on these artists. Okay, I'm gonna go back to my bio sheet, and Joselia, if you're ready, I'm gonna have you be our next artist in the queue. Joselia was kind enough to send a very succinct bio. Joselia Rebekah Hughes is a working poor. Afro Caribbean descended writer, editor, access provider and interdisciplinary teaching artist surviving in the Bronx. And that's it. So please take it away, Joselia.

Joselia Hughes: Hi! Can everyone hear me? My, my computer's been on the fritz. To begin with an image description. I am a black woman wearing corn row braids in the front, and box braids in the back. There are clear beads or clear break beads on every braid. I have small green glasses. I'm sitting in bed against blue and orange pillows, and behind me is a blue, white, and black painting that I made some years ago. I'm also wearing all black, a black hoodie and a black tank top. I start with an image description because so much of my work concerns space. And how do we navigate space for bodies of different capacities? I suppose I'll start with access work and sort of move towards the other things. Access work is very layered. It's not always understood as artistic work. It is often understood as sort of like amorphous supportive work that is only needed to kind of like check a box instead of provide capacious emotional and somatic experiences in space and time. And so the access work that I primarily do is audio description, and verbal description writing. I do it for individual artists as well as institutions. And I'm gonna start sharing my screen really quickly to sort of give you an idea of what a verbal description can look like. Alright. So earlier this year, the Whitney had an exhibition of Henry Taylor's work, and I described several of them. And I'll choose a brief snippet from one of them. “The Times They Ain't Changing Fast Enough” is an acrylic painting on canvas that's 6 by 8 feet. The painting is like.

Bert: Joselia, just so you know we're looking at your folder, your

Joselia: You can’t see the screen. You're only looking at the finder.

Bert: That's right.

Joselia: That's strange. Okay, that's not good. Sorry all.

Bert: I've done so many wacky things at this symposium.

Joselia: I don't know. I'm gonna just start somewhere else because I don't know what's going on with this computer. Okay, where do I begin? I feel very frazzled.

Bert: Understood.

Joselia: Yeah, I'm a writer, and primarily my work orients around this question of “what is ability?” I think I have a really hard time sort of addressing what it means to be disabled, until I can understand the word that has the prefix which is able. I can say that this concern has been longstanding. I'm 35 years old, and sometime in my mid teen years I got obsessed with a certain branch of philosophy, and the word ability kept coming up. But I never quite understood what ability was, and this persistence, this kind of itching around, the word continued. And in the last few years I've really been trying to understand the relationship between or rather, I've been trying to understand one of the definitions or several of the definitions of ability that have come out of the transatlantic slave trade. Once they looked at the etymology of ability and understood that “able” really meant “to hold”, I started thinking about physical manifestations of hold. I was then led to the slave ship. The hold of the ship is where enslaved persons were kept, and through some reading and some research it became evident that the slave ship was not merely a vehicle of transportation, but it was also a vehicle of transformation, and everyone on the boat, whether they were on the deck of the boat or in the hold of the boat, was being transformed in the process through this idea of ability that would then translate onto plantations in the Caribbean and North America, North and South America. So that's like kind of the conceptual framework of where I'm always at, what is able, who is able? How can one be able? And I'm gonna try to share my screen again. And let's see if this works.

Bert: Cool.

Joselia: Can you see the screen.

Bert: Yeah, we're seeing like a PDF or a Word doc. And now we're seeing-- Now it's the finder again. Okay, now it's an image.

Joselia: Awesome. Okay, in 2020, I got hospitalized for sickle cell crisis. I was born with sickle cell disease. I also have ADHD and I identify as mad, and I was convalescing shortly before the COVID pandemic began. And like in April of 2020, I drew this, it's India ink and alcohol marker on paper, and the text says, “Able for work”. But I put a box around F, to sort of indicate F is function. I think about a lot of my work in the context of mathematics. And I am always trying to think about like, where does ability act as a substitute for effort? And in which ways do we kind of invisiblize the labor expenditure of disabled people? So that's one. Let's see. I'm gonna take this off and just show you something on the screen, because that'll be easier. Oh, this is really hard. Wow! Super distracted. I guess I'll just share this other project that I've been working on for quite a while. So in 2021, I was commissioned by the Institute of Contemporary Art to make an edition for their store. And I made this project called Verbena's Apothecary. Now, Verbena's Apothecary is based upon this conception of, where does the domestic show up in public space? I'm also really interested in the collapse of public space, especially as this COVID pandemic continues. And so I made pill bottles. I made a series of pill bottles, in which I created a variety of labels, and each pill bottle was filled with a poem or 2 poems. There were 21 poems in total, and so in a set of pill bottles you could get anywhere between 3 and 5 poems. And essentially the idea was that you read the prescription, and you give yourself the prescription for the day. So, for example, this pill bottle says, “Read inattention as reclamation of energy from an attention economy”. Or this blue bottle says, “Read if it hurts deep down beyond measure, incalculably, glaringly, where meaning and sense escape”. And so those bottles were sold and people could buy them, and the intention was that, like people would meet other people with the bottles and you'd trade bottles. And there was this kind of effort of community care within it. I made another iteration of this project, for Finnegan Shannon’s show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland. The show is called “Don't Mind if I Do,” and the show is really cool, because, instead of having of the participant or the visitor going to the art, the art came to them. There was a conveyor belt setup in an exhibition room. There were a variety of chairs, and each visitor could interact with the art. And so I sent these bottles. These are actually the very bottles that I sent, and instead of filling them with my own work, I filled them with random objects from the dollar store. I'm really interested in the curatorial decisions of stores, particularly dollar stores, and where they show up and where they don't, and what that says about the community and community need. So I filled the bottles with a variety of things, everything from like white out to tea tree oil to candies, that participants were able to take. The candies had some kind of medicinal or herbal quality, helping stomach aches, low blood sugar, that kind of thing. I also filled the bottles with blank sheets of paper and golf pencils. And so I instructed, I wrote a letter to the participants because I wasn't there for the opening, but I did want to have an intimate touch, and I asked them to write their own prescriptions and to leave them in the bottle. I received so many, so many prescriptions. There are literally hundreds. There are prescriptions from people who are finding out that they are recently disabled, people who are long time disabled, people who were grappling with loneliness, with heartbreak. Grappling with joy. The variety of notes felt like the most intimate feedback I could get. And sort of understand the waters of where we are right now. And have people express their need and have a space to express their need, while simultaneously contributing to something that they often feel excluded from. A lot of people commented on how they never thought that they would get to participate in an institutional show, and I think that really hurt me. I felt very hurt. I don't particularly feel comfortable in institutions, and I understood for a variety of reasons, and I understand why other people wouldn't, and it felt really important to hold that space open if I could.

Bert: That's amazing.

Joselia: So yeah, that's like my work. I guess I could also just briefly say that I have a chapbook coming out. It's called “I Need Fucking Space Like Fuck.” Yeah, kind of intense title. But it exists in a lineage of black linguistics and black literary theory. Primarily, I'm responding to Percival Everett's 2001 book “Erasure”, which was recently adapted in Cord Jefferson's “American Fiction,” and I would just like to note that those 2 pieces of work really do focus on these sort of like black male protagonists. But the contention of both of the works is the contributions of black female writers. And so I think my expression here, or my work as a black woman, disabled person, is to articulate that, “Yes, we are here. Yes, we are doing it. Yes, we have thoughts”. And those thoughts do not need to be collapsed into a singular disabled culture. Thank you.

Bert: Thank you. That's incredible. So yeah, people can, you know, clap on the inside. And we will share all the love we can via Zoom and the Internet. So I'm going to read the next bio. Thank you so much, Joselia. Dominic, I'm going to have you go next. Dominic Quagliozzi, he/him, is a multidisciplinary artist and arts educator. His work reconciles his lived experience with chronic illness and disability to explore personal histories and the domestication of illness using medical materials common to hospitals: hospital gowns, scrubs, and clinic table tissue paper, to name a few. He references his de- and reconstructed body, often present through its absence. By repurposing and recoding medical materials as art making materials, he explores the emotional and psychological space in these moments of vulnerability, anxiety, fragility, and resilience. He received an MFA in studio arts from Cal State University, Los Angeles, and a BA in sociology from Providence College. His work is in the permanent collection at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, and then the rhizome.org digital archive. In 2018 he was on the keynote patient panel at the Nexus Summit for Interprofessional Care and Education at the University of Minnesota, and he is on the Arts Council for Creative Healing for Youth in Pain. Dominic!

Dominic Quagliozzi: Thank you for having me, really excited to be here. I'm going to share my screen, if I can remember how to do this. Okay, so are you seeing me or the screen right now?

Bert: We're seeing your Powerpoint, or your Google slides.

Dominic: Okay. So I I kind of went a little quick. I was gonna do an image description. But I I'm a middle aged white male wearing glasses, currently in my studio. A little internal description. A little rainfall today, my son is was sick, so I was up with him pretty late last night, and so for that reason I'm using notes which I don't usually do when I give artist talks, but for interest of time, and to stay on task I wanted to use just some bullet point notes. So again, my name is Dominic Quagliozzi. I'm calling in from Worcester, Massachusetts, unceded Nitmuck land. So I wanna just start with a little bit of some historical work I've done, that's about 10 or 11 years old, that kind of sets the context for the current work I'm making. A lot of my work revolves around personal, raw experiences within the medicalized industrial system, having cystic fibrosis. I was born with that genetic disease and spent most of my childhood and teen years in the hospital, and then again in my late twenties, when I was listed for a double lung transplant and waiting in and out of hospitals again. So these first few works are public performance social actions that I did, kind of thinking about isolation and the private aloneness of chronic illness, and where you do your treatments and take your medications, in these spaces that are private and in your home, or whatever. I wanted to bring those out into public shared spaces, to kind of create a public sick space. Obviously these were done pre-COVID. So the interpretations of these works over the last few years have been very interesting, to see how they've changed. But so this was done at LACMA, in front of the “Urban Lights” sculpture by Chris Burden. He mentions taking the function out of these streetlamps by making them sculptures, and I thought it'd be interesting to give them function back by making them an IV pole, where I then infused antibiotics for the course of an afternoon. Here's the IV bag. Here's another performance I did around some sidewalks in Los Angeles, where I did a treatment for cystic fibrosis. This is called “the vest”, along with airway clearance and inhaled nebulizers. And I did these throughout the day, on the schedule of my normal treatments. And so I'm trying to think about peeling away the levels of internalized ableism that prompted me to keep my disease hidden throughout my life, like even some close personal friends in high school never knew I had CF, because I kept it so hidden. And by the time I reached my twenties,

that alone was debilitating, and I needed to reconcile that. And so I did that through performance art, and these what I call social actions, or social interventions, really, and also this notion of performing illness. Cystic fibrosis is a relatively invisible illness, but I wanted to make it visible and interactive through the medical devices and the treatments which I was undergoing. So here's “The Hospital Show.” I did this in 2013, where I kind of reversed the public/private space, and instead of bringing my treatments out into public, I brought the public into my hospital space. I created work for 2 weeks while I was in the hospital, dealing with basic human emotions and functions, these very simple drawings. And then I created a press release, I got some critics, some gallerists, some artists, my friends, people came to the opening, and then I had it open by appointment after that, and it was kind of like this idea of bringing the public into this sterile space of care to reveal the care apparatus, and also thinking about the choreography of the public, having to navigate the halls of the hospitals to reach the patient room. And then again the hospital room, as both art studio and gallery. In 2019 I created “Suit”, which was from some hospital gowns I wore during a few surgeries, and I'm thinking about the dichotomy of being a sick person or a healthy person, and we're kind of forced to make that decision. Forced to make the choice to be a healthy person if we're out in public, and the responsibility or the fluidity of responsibility between being a sick person or an able-bodied worker, and the demands and expectations of being both. And to me, I've kind of feel like it's cosplaying: when I'm out and and trying to work and being a parent, or whatever it may be, I feel like I'm cosplaying a healthy person. And then, when I'm in the hospital, even though I do have some ability and levels of debility and levels of disability, I'm cosplaying a sick person. So I feel like I'm always caught in this weird tension of trying to exist in all these worlds. Here are some fragility drawings I did on clinic table tissue paper, where I kind of work the graphite into the paper to see how much it can hold, and then, as it starts to tear, I go through and repair with thread, but that action of repair also tears it more, and leaves holes and makes it more fragile. So it's this balance between trying to preserve the longevity of an a material that is made to be discarded and soaked with human sweat and emotion for these times when you're in getting treatment, or having a doctor's appointment and whatnot. And here's just a quick video of one of them moving. I can get that to go. So I keep these loose so, as the viewer walks by or people walk by, they respond to the presence of the body. And then I just have 2 more slides here. These are called “Transformers”, these are wood wrapped in hospital gowns and hinges, where I allow the viewers to come up and have this tactile sensation with hospital gowns, thinking about like, most literally, like touching a patient. This is another one where it's the front view. And then 2 manipulated views. And to me like this is the idea that different viewers can come in and leave the object looking different for the next set of people that come in and look at it. This transitory element of touch. And there's a group of them at a show in San Diego. And then, lastly, I wanted to just talk about synthesizing some of the medicalized experiences I've had into the work. This was from an installation in Sydney, Australia. But I'm gonna focus on “Wishing Well”, which is the ground piece. That green piece. it's on the end there. It's surgical linen, hospital gowns, and colored pencil with moving blankets and parts of recycled paintings that didn't work out. And so these wishing wells here in the middle, they're like lawn ornaments, and throughout my experience, waiting for a transplant, a lot of people were saying, “Oh, like I'm hoping you get new lungs”, and “I'm praying you get new lungs”, and I appreciated that. But for me it was like this dark side of that had to be someone else dying for me to get those lungs. in this weird like conflict inside of me, this tension again. So the bilateral lung transplant position they put you in is this first slide here. And then so I kind of use those 2 as like the synthesis for this piece. Thank you so much.

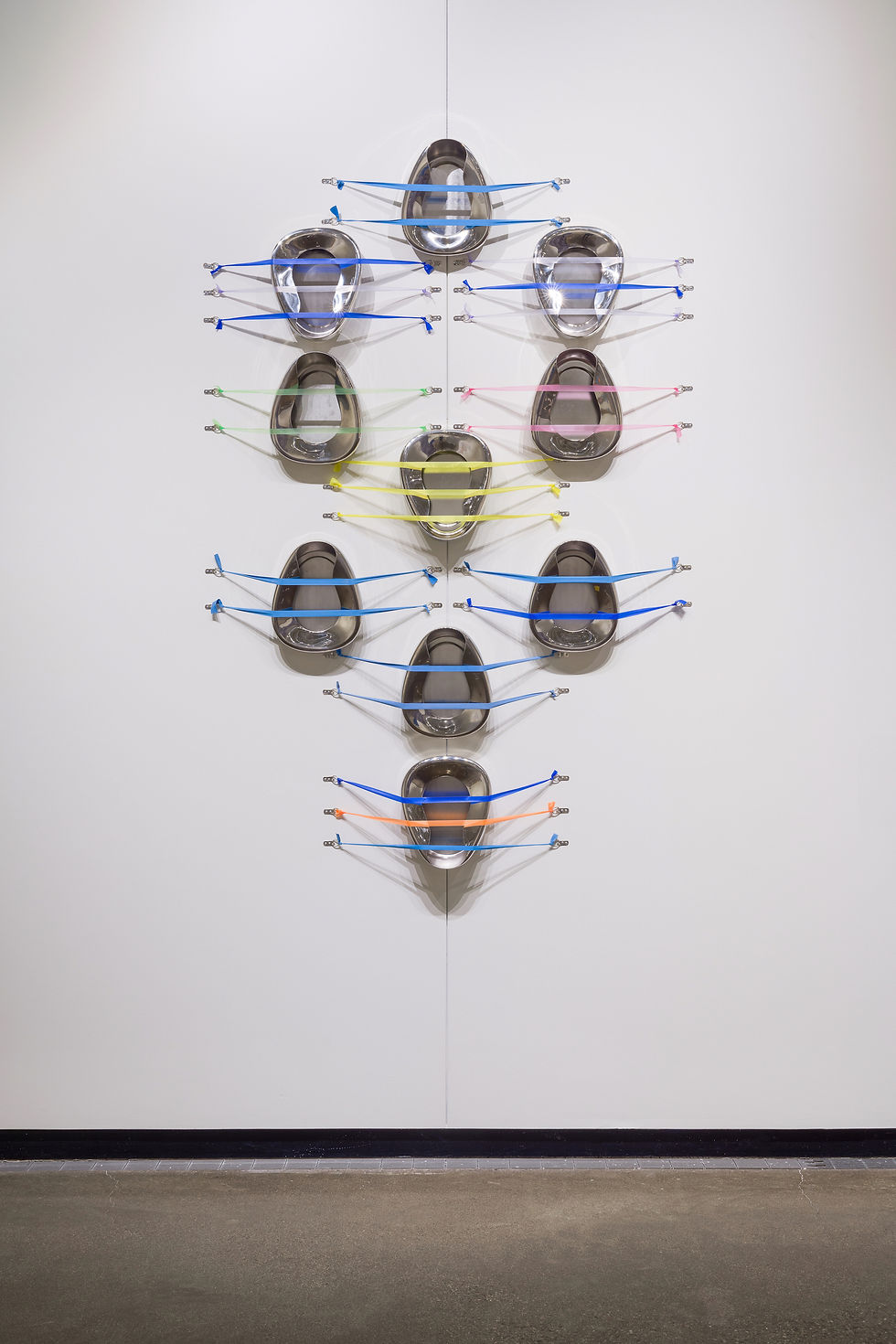

Bert: That's awesome. Thank you, Dominic, that's wonderful. It's some stuff I hadn't seen before. So we have 3 more people, and we'll be in here hopefully until everyone has spoken. But I understand that people need to leave, either the Zoom room or the real room. I was keeping out of this, and I wondered if it would do the same on both screens and logged in twice, which I don't know how that works. Okay, I was gonna have Mae Howard go next. And I'm going to, sorry, my desktop notification. Mae Howard! Mae Howard is a visual artist and ritualist, whose interdisciplinary approach extends across research based, participatory in collaborative projects, ranging from lens-based media sculpture, installation and performance. Calling upon lineages of disabled trans care work, Mae is interested in the embodied fleshly and material enmeshments of BDSM, the medical industrial complex, biopolitics and disability. Their work explores the residue of discard, debilitation, and excess. Their work has been exhibited in New York, Berlin, Mexico City, and Philadelphia. They are currently a 2023-2024 fellow in the Whitney Independent Study program, and a 2024 fellow in Emerge NYC, through Vax Arts. Thank you. Mae.

Mae Howard: Hi everyone. My name iss Mae, I use they/them pronouns, I'm a white person with a like kind of grown out shaggy brown mullet, and I’m in a maroucherouched-esque white button down shirt. I'm sitting on a black couch, and there's a white blurry background behind me that's a bookshelf. I'm gonna talk today a little bit about some projects that kind of have led up to my current practice, and then share a little bit about a project I'm kind of finishing up right now. That's not what I wanted. Can everyone see the slideshow? Oh, okay.

Bert: Not yet.

Mae: Let's see, there we go. How's that?

Bert: Yeah, we see some text.

Mae: Okay, great. So I wanted to start off with a quote from Amber Jamilla Musser, whose book, “Sensational Flesh: Race, Power, and Masochism” has really impacted my work. So this quote reads, “The knowledge that comes from illness is something that cannot be produced only from experiencing the body. Whether this is desired or not, the illness is not exactly an external agent. It can render the body powerless, but the body and illness are not entirely separable, so that when one surrenders to illness, one is also surrendering to one's own body, and not something strictly definable as outside.” This quote, and I feel like her book at large, is kind of speaking to BDSM practices, and the racialization of care and relationships, has been really influential to the work that I make. And so I wanted to kind of start with a quote from Musser. I'm also gonna state right now, before I show an image that this 5 to 7 min presentation will have images of piercings/BDSM. So if that's something that you don't want to see, you're welcome to leave and come back in like 5 minutes. So the first project that I wanted to talk about is a project called “Immobility Appendage 1”. This project is a performance where I am kneeling at a prayer bench and getting pierced 13 times on each side of my back, and then strung to the walls. And for this project I was really interested in questions of perception when it comes to pain and wounds. So specifically, I'm really interested in the way in which the tacit wound kind of comes into play with this piece, where one is kind of observing a piercing performance, and may kind of experience somatic responses, ranging from pleasure to disgust to fear, while maybe not recognizing that the actual pain and embodiment of pain that I in my own body am experiencing, is actually coming from the position of kneeling, not necessarily the piercings themselves. Another kind of object of interest for me within this project was exploring what one would call the “disabled body,” in quotes, as beyond a surface that can be projected onto. And so to me, the piercing and the kind of entering through the flesh was really important to me. Also I forgot to do an image description. So this is an image of me, a white person with at that time like a messy blonde mullet and 2 small braids, facing a wall, you can see my braids and ears, and my head is kind of pressed up against the wall. You can't see my face. And then on my back are 2 columns of 13 needles with little like blue sharpie marks to demarcate where the piercing would go through, and then some kind of thin, clear thread coming out of each needle. My next project, “The Tetherings,” explores what Leah Lakshmi Piepzna Samarasinha calls “the cosmologies of mess.” So I was really interested in using the used tubing from the medical industrial complex, a lot of which from my own experiences, others from friends. So I would take this used medical tubing, and then also bought new medical tubing, and begin to kind of maim, braid, cut up and twist the tubing to kind of explore the afterlife of this excess material that's usually just discarded. On the left is an image of one of the sculptures. It's kind of amber brown and clear. It's hanging from a a steel hook in the ceiling, and then the windows on the left side are kind of casting a light, so there's a minor shadow in view at the bottom of the image. And for me this project was both about, I guess, exploring the materiality, but also kind of thinking about as an artist what it means to go into trance when making, and so the process of making these involved really heavy long sessions with a heat gun and this plastic, which is deeply toxic. So itIt also brought up questions for me about toxicity, where one registers toxicity, as in my medicine that I'm taking, that is also toxic to my body, is probably not being registered as toxic, whereas the melting of this plastic and the release of these fumes is being registered as such. I wear like a face mask and stuff, but I would still get lightheaded and have to take breaks, so beyond the tubes and the use of the tubes themselves on the right side, you can see this, like it looks kind of like a pigtail like from an actual pig, not the hairstyle. At the top, there's this like elastic banding, and that is physical therapy banding. It's also kind of run through a lot of the tubes. And so I was using the physical therapy banding to kind of allow the tubes to hold shape, and as a gravity mechanism within the sculptures, to not only rely on kind of smaller medical armatures, and these physical therapy tubes, and then the banding itself, which you can see on the left image, that like white section at the very bottom, that looks like gauze on the tubes, is actually melted physical therapy banding. So I was interested in bringing in elements of physical therapy, as someone who's had to go to physical therapy, and have it actually cause more harm for my body than good. So again, just like thinking about the decay of these materials themselves, and the ways that they can be used in their afterlives. My next project was “Offerings to Bob Flanagan”, which was a yearlong project, performance piece and syllabus creation, in response to Bob Flanagan's “Pain Journals.” For people who don't know, Bob Flanagan was a masochist with CF who died in the late nineties. He died a year before I was born, but was kind of very active in the BDSM scene and in the performance art scene, in both LA and New York, in the late eighties and early nineties, and his book, “The Pain Journals”, documents his experience with his daily regimens and struggles with cystic fibrosis. And so this piece, “Offerings for Bob Flanagan”, it explores Flanagan as this kind of like ghostly figure or haunting within my own life. And also explores this idea of disabled ancestry, which I think a lot of times is applied to people like Audre Lorde, which I think is both wonderful, and I think the idea of disabled ancestry is kind of broadly applied to people, and I see a lot of like whitewashing of those people. And so I was thinking about what it would mean to kind of claim ancestry with someone who is white and kind of problematize his figuration in art history, as well as like my own idolization of him, while kind of documenting my own experiences of pain. This image shows a Mies van der Rohe leather chair, the MR10. It has like legs that kind of curve out like a wheelchair that are chrome. It's brown, and then on the back and on the underside, which can't really be seen that well, there's kind of a leather cord corset stitching that I added. And then in front of the chair is a monitor that shows a bed with white sheets, and yellow subtitles that read “with a fist raised as the protest goes on outside”, which is a quote from Johanna Hedva’s “Sick Woman Theory.”. Below the monitor is like a small speaker bar, and then a chrome and orange low boy stand is holding up the monitor. So I was interested even in the names of the materials that we're holding the bar and the monitor, like “low boy” almost sounds like it's referring to something, some sort of like SM relationship, and I was interested in that apparatus and that name kind of coming into the project twofold as well. And then, lastly, I mentioned it being a syllabus. So thereThere are quite a few disabled artists, scholars, activists who are mentioned, and so the piece itself kind of creates a syllabus of broad critical disability studies, disability justice, activism, etc. And the piece is meant to be viewed in a solitary viewing kind of arrangement. So it'sIt’s one viewer at a time, facing the screen, and the screen is next to a window, or close to a window, to kind of increase the screen’s viscousness. So theThe viewer ends up also seeing themselves while they're watching these pain journals that I wrote to Bob. This is another slide from the video. It's of another picture of my bed, with a blue heating pad, blanket, a lamp that's on on the left side, and then a hamza and an evil eye on the right, with a dried bouquet of flowers and yellow subtitles that read “this fibro subspace craze is giving me the spins.” I think this is the like third to last, so I'll just run through this quickly. Alongside my studio practice. I'm also an educator, newly, I teach at Penn. I teach critical disability studies, and I've kind of been working with the institution to establish a sort of series of courses that students can take, after a lot of organizing with both graduate and undergraduate students, cause Penn has never had any of these classes before, and I felt like that curriculum was really important to kind of introduce. But before that class happened, I ran a working group called “Disability, Debility and Form”, which was an online, free and open to the public working group, where we would do readings and have visitors come. So on the left is a flyer that's like purple with an orange-ish sun and a black circle in the middle with the names of the speakers for the fall, who were Amber Jamilla Musser, Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, and agustine zegers, and then on the right is an image from the spring programming, which is a blue background, with again the same orange sun, a black middle, and it reads the names of the spring visitors who are Kalindi Vora, Jina B. Kim, Johanna Hedva, La Marr Jurelle Bruce, and Amalle Dublon. And this program, while funded by various groups at Penn, was open to anyone. So we had students from UCLA, I had friends, professors, people, or just artists in New York, and I was really interested in the way that we could kind of learn collaboratively and build knowledge skills together, especially around texts on disability and debilitation, given their density at times. So it felt really important to have that kind of become a collaborative and group effort, instead of me just reading alone in my bed. This is an image from my newer series called Crip Gimp. It's an image of a medical divider screen with the plastic kind of waterproof material in the middle that's cut out and replaced by 3 silk screens that is displaying an image of me in a sex swing, wearing a leather straitjacket, and a gimp mask with my oxygen tank, or my oxygen concentrator, plugged in and running. So there's like a clear tube of oxygen running from the bottom right all the way up to the middle of the frame. This piece is mobile, so it can be moved in various galleries or art institutions. And I chose silk because I was trying to poke fun at this idea of like medical divider screens actually providing privacy, wherein the screen kind of divides two people spatially, but doesn't necessarily provide privacy. As in, I can usually hear the patient who's sharing a room with me, or who's on the other side of the vaccination fake wall, etc., while they're receiving treatment, and thinking about kind of the intimacies that kind of bleed in and out of what the screen is claiming.

Bert: Everyone be sure to check your mute. I can't really, I don't see who's-- If you're not muted, could you please make sure you're muted?

Mae: And then, lastly, here's an image of my studio right now I'm currently working with on the left, and the middle of the image is a Hhoyer lift from the late eighties, early nineties. It's chrome plated and it's used to transport people from their wheelchair to bed. And then on the right is a bariatric trapeze, so it usually straddles the bed, or is on one side of someone's bed, and they're usually able to like pull themselves up. So kind of increasing the mobility that a person would have in transport, and then on the right is a bust that actually just came out of the fabrication lab like 3 days ago. It's an aluminum bust of my body right after top surgery while I was still inflamed and kind of quite sick from the meds and the procedure, and I was interested in casting it in aluminum, as kind of a celebration and acknowledgement of my wheelchair, and its presence and importance of my life. My wheelchair’s also made out of aluminum, and so this bust will hang from the hoyer lift on the left suspended, and then the bariatric trapeze on the right will have a meat hook. It's going to be black with the handle from the trapeze element balancing on top of it, and these will be on view in New York on May 9th, at Westbeth Gallery, for about 3 weeks. Okay, I think that's it. Thank you.

Bert: That's fantastic. Thank you. Mae. And we're now at 1:01 our time. If people have to go, that's fine, we will definitely keep going, and everything's being recorded, by the way. So if you do miss some of the presentations, they will be on the Institutional Model blog, once I clean up the transcript. You can also contact me ahead of that time to see the video that's being recorded. So again, if you can stick around, please do. We have 2 more incredible artists who are going to speak. The first artist, or the fifth artist, sorry, in our line of 6, is gonna be Darrin Martin. If you're not muted, please if you wouldn't mind, mute yourself, Darrin Martin engages the synesthetic qualities of perception through video performance, sculpture, and print based installations, influenced by his own experiences with hearing differences. His projects consider notions of accessibility through the use of tactility, sonic analogies, and audio descriptions. His works have screened at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Pacific Film Archive in California, Impact Festival, Netherlands, European Media Art Festival in Germany, and many others. His installations have exhibited at venues including The Kitchen in New York, Grand Central Art Center in California, Aggregate Space Gallery in California, Moscow State Vadim Sidor Museum in Russia, Mackintosh Gallery in Canada, and most recently at Somarts, California. Martin received his art degrees with an emphasis on video and sculpture from Alfred University School of Art and Design, BFA, and New Media and Installation at University of California, San Diego, MFA. He has had artist residencies at Site Internationale des Arts, Eyebeam, Experimental Television Center, Signal Culture, Shawn North and Wasaiac Project. Martin also occasionally curates exhibitions and video screenings. Born in New York, he lives in Oakland, California, and teaches art at the University of California. Davis, Darrin, welcome.

Darrin Martin: Hi! I should have edited that down for you. Sorry! So thank you, thank you Bert Stabler, for inviting me and thanks to all the other artists. I'm really enjoying the presentation so far. And I'm coming to you from unceded territory of the Moiku Alani people in Oakland, California. I'm gonna try something a little different and show a set of timed slides, except for the first one, while reading a a kind of broad statement history about my practice and influences, cause I notice I get a bit nervous and anxious under a tight clock. So forgive me for not audio describing the slides. But I will start with an audio description of myself. I'm a middle aged Caucasian guy with chestnut hair and a mustache with some gray sprinkled in to that. And I am wearing just a gray sweater, and a gray, furry sweater on top of that. And my background is is blurred, I'm in my studio. So I'm gonna jump right into my slides, bear with me for a second. Here we go, share. I was born a month before one of the biggest television events of the sixties, the first walk in the moon. My parents checked the spelling of my name by watching the credits roll from the popular television show Bewitched. I suppose I could consider myself a child of television. However, born before VHS, my parents were already sick of the novelty and expense of their super 8 film camera. So I did not grow up accustomed to seeing moving images of myself. My first exposure to film and video as means of artistic expression was at art school. The structural films of the 60s and 70s stripped film away from its conventional use as a vehicle for narrative, addressing instead its essential properties and codes, contained within the medium itself. Video art pioneers like Naim Jun Paik spearheaded investigations and images and sound processing through hacking into existing electronic devices or teaming up with engineers to make new ones. I was exposed to ways in which these mediums could be altered, using both analog tools and early digital technologies. This curiosity to explore new tools and processes was tethered to my interest in manipulating the stability of the moving image, while simultaneously exploring its sonic equivalents, and much later upsetting the privileged position of the binaural. Feminist artists, such as Carolee Schneemann and Adrian Piper used their bodies in performance, film and video to illuminate avenues of resistance to patriarchy and racism. Internationally, artists like the Viennese Actionists and the Japanese dance movement Butoh helped me consider the body through both expressive and transgressive acts as a response to the violence of the modern era. I came of age in the late eighties and early nineties as a queer youth, viscerally feeling the threat of AIDS through both contemporary art and media. I face the undeniable fact that the body is politics. Through my practice I've continued to struggle to find ground between concerns with the potentials and distinct properties of the various media I explore, and a need to express my own subjective inquiries related to difference and otherness. While many of my earliest works engage with reflections upon queerness and sexuality, for over 20 years, beginning with the new millennium, I've made works that have been informed by my own experiences with hearing loss and its synesthetic impact upon my other senses. Eventually, moving beyond the idea of loss, I had the privilege of working with a group of artists and scholars and disability studies, considering broader cultural expressions of disability and access. Together, we develop ways to in which to consider notions of accessibility being built into a work of art at its inception, rather than as an afterthought. Open captions, audio descriptions, and tactile investigations have expanded and complicated my practice, as much as I'm concerned with their perceptual notions of access, I'm also curious about the ways in which our observations of the world are consistently augmented and filtered through ever-changing technological processes. Since the pandemic I've been questioning how I might be positioning myself as a body occupying a space in a home and studio that is somewhat new to me in Oakland. Whose land am I occupying, inside a literal bubble of the safety of my backyard and studio? What are crip ecologies? How do they become so? Is it the air thick with smoke from wildfires, making every breath we take a privilege? How does our existence intersect with the throwaway culture of late-stage capitalism? How can we resist? How might we embrace an array of vulnerabilities and recognize our own incompleteness? How might we negotiate and embrace interdependence and care? Expanding upon some of my own curiosities for the potential of access, I've also begun curating screenings with the idea of access tropes, such as captions and audio descriptions, being lenses at which the meanings of the works reside. Recently I worked with the Ann Arbor Film Festival to showcase a screening of artists placing captions in our audio descriptions as primary seeds to their creations. I also collaborated with Electronic Arts Intermix in New York to reframe video artworks from their archive through an accessibility lens. The process will be published this month as an essay titled “Experimental Modalities, Crip Representation and Access with Electronic Arts Intermix,” in a special crip edition of Leonardo this month. That is my presentation. Thank you.

Bert: That was great. Great.

Darrin: Thank you.

Bert: Yeah, so much amazing visual stuff to go look at. If you haven't seen Darrin's website or his Vimeo channel, you can spend happy hours like I did working on Darrin’s profile, looking through his extensive history of video art. Thank you, Darrin, yeah. And thank you so much for your patience, everyone who's here, but especially Cielo Saucedo, our sixth artist, and by no means the last in any sense. I'm super excited to have Cielo finish up the sequence today. Cielo Saucedo is a disabled artist and access worker from a family of migrant farm workers. Their work focuses on the dispersal of ableism through cultural economies. They work to dissolve the curative aspirations of technology. Their work encompasses computer generated imagery, sculpture, machine vision and virtual reality. They received their BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and are currently an MFA candidate at UCLA. They are currently, an Eyebeam Democracy Fellow, and have shown work and lectured in Los Angeles, Chicago, London, Quito, and New York. Thank you. Cielo!

Cielo Saucedo: Hello, everybody! Thank you so much for sticking around. Just for a quick image description, I'm a light skinned Chicana who has kind of like a black half like one shoulder top, I have a little bit of tattoos, my hair is sort of in my face, and I have kind of a blue background. And I'm also in bed. I'm just thrilled to be here. I have a lot of mutual friends with the rest of the speakers, so I just wanna express my thanks. I'm coming from unceded Tongva lands. On another note, sorry, I trip up on myself, I have a little bit of a stutter, so, otherwise known as LA, and just as we acknowledge the histories of genocide and occupation marking the lands we live on, I think it's really crucial to acknowledge the colonial violence unfolding in the present right now. So before I start, and how I kind of want to reorient the room is just to affirm my solidarity with global anti-colonial struggles for a free Palestine. So I find myself doing a lot of these talks, especially lately, and everything, every presentation's a little bit different, and every presentation, I mix it up. And I kind of talk about, or I kind of think about these presentations as a way to kind of think through my practice, make new conceptual bindings, I think. So I'm gonna share right now. I just want to start off with the fact that I make work with people all the time. But the image description of what you see on a screen is 3 people who have been 3D scanned. And they're 3 white people, and the artifacts of the 3D scan is still present in the image. It's crunchy. It's disfigured, if you want to think about it that way. And this is a cripping CGI collective of disabled…

Bert: We haven't seen any images, just FYI.

CIELO: Oh, really! Oh, no! Whoops I didn't even share. That's so funny.

Bert: I don't know if you're gonna preview it and then show it or…

CIELO: So funny. Well, yeah, now y'all get to really imagine it, decenter the visual. So here is the image that I was describing. And this is a collective that's related to me cripping CG, and we're disabled artists and access workers creating and archiving at the intersection of disability and computer graphics. So we were awarded the Eyebeam Democracy Fellowship this year, and we are trying to complete an open source digital asset library of disabled life and computer graphics. So the bulk of it is community-sourced motion capture, animation, custom-made avatars and portrait avatars. So the library is operating simultaneously as a practical open source resource for digital artists and a record of online crip culture. So we imagined disabled digital presence as explicitly political and complicated by the entanglements of desirability, stigma, and medium-specific abuse of disabled embodiment. Think about Resident Evil, think about different kinds of tropes that show these modified gaits as a space of horror, so we want to antagonize these distortions, these disparities of bodily difference within these spaces. I was trained as a 3D animator. I went to SAIC, and I studied with all of the great 3D animators there. So my entry into the digital and my entry into the virtual is underscored by my debilitation, and I think specifically with my work, you can see a journal article that Nat and I wrote. Nat is in the room right now, a really dear friend and collaborator, and you see Nat on the side, they're a person using a cane and mobility aids, putting motion capture modules, accelerometers on actual mobility aids. So the virtual I see as this kind of space of not complete agency, but as a way of like redefining what a debilitated body might be. And I think what I was saying is that I think of disability as a distinctly political position. So often within this talk you're gonna hear me speak about like impairment or debility more often than disability, because I feel like disability often exists in the North. And to be disabled anywhere else would be, is not the kind of language that's afforded to folks. This next work is called “Cadaceus”. So I have been working a lot with mattresses, and so the image is a mattress, a blue mattress, with these inlaid light panels, and the light panels are glowing, and they're Social Security documents inlaid with copal. So copal is a preamber. I've been thinking about this kind of material as a way of freezing time lost to bureaucratic processes. So, disabled bodies are fiscally imagined as beds. I'm really leaning into Marta Russell, right now, in her imagining of these economies in which people are forced into carceral welfare systems, only to be pushed into different kinds of medical abuse. So I'll read a little bit about it, because I can probably read better than I can speak off the top of my head. So, “disabled mind-bodies are seldom given access to the distinction of worker. They're cast as economic drains, despite discriminatory access practices or discriminatory hiring practices, and ADA accommodation law that favors employers. So disabled subjects turn to social services for their needs. The United States subdivides those services to reclaim this population as a site of financial reproduction. This is actualized through the allocation of public funding, through the projection of beds, beds or the number of bodies that can be housed and treated within hospitals, prisons, and extended care homes are capital stock, and drive the amount of money contractors receive from the government, by creating a forced dependency on welfare systems, private and non-for-profit institutions and businesses produce value for the private sector through policy-driven contracts using public funds. So this ensures that while disabled mind-bodies cannot be exploited for their labor, value can still be extracted from them.” and let me go so-- you can see, it has my deadname on it. I was really really ill in Chicago, and I got denied for SSI, and I was just kind of mourning the loss of that. And it's a closer picture of a drip of copal on a document that looks like a tag coming out of a mattress. And I think so much about this form, this horizontal shape formally, specifically how Rosalind Kraus thinks about horizontality as a literally a disabled form, as an anti-form. So if we think about the vertical, if we think about this kind of like this phallic triumph, as being kind of like a fighting against gravity, or it's like pure triumph. The horizontal, then, is kind of like an anti-form. It maybe motions to a kind of dreaming, it motions to spaces of rest, which can be dissent. So this next work it is a cane that has a short handled hoe tied to it, and it's piercing a “Silent Spring” by Rachel Carson. It's a first edition, I was really lucky to get it. So this work is called “Short Handled Hoe, Stand Up Straight and Get to Work. Squat, Laborious Girl, I Pray for You”. And so what I was thinking so much with this work is posture, what I use to keep my posture, and posture as surveillance as well, within these kinds of ecological death world in which we live in. So the short handled hoe, or El Cortito, was a surveillance device utilized in agricultural fields of the southwest region of the United States. So it was introduced in California in the late 1800s, and basically the usage of that tool helped develop state high yield monocrop agribusiness, and what the short handled hoe forces a farm worker to do is to perform hard labor, bent forward from the waist down with their legs, mostly straight for the majority of their workday, up to 12 hours, prolonged time when this posture leads to chronic pain, limb difference, spinal degeneration, and permanent disabilities. So these worlds or these fields are becoming death worlds and my family worked in the fields. I am first generation from Mexico, born and raised California or LA, specifically. So if workers were to straighten their back, their posture would change, and that would alert the foreman of their pause in labor, leading to punitive action. So to deal with this harm, what workers did was work faster. So once they got to the end of the row, they were able to stand up straight and relieve this pain. So what this did was increase profitability for agribusiness, and it also boosted waste. Essentially, it basically allowed for a quicker turnover of folks to come through, because people were basically getting debilitated constantly. And there was like a huge rush of migrants coming through. So in 1975, they banned it. But because of certain legal protections inside of fair labor standards, they weren't allowed to make it a legislative bill, because for a long time most farm workers were generally black, and thus foreclosed from labor protections under the logics of chattel slavery. So because of this historic legal discrimination, the abolition of the short handled hoe used like a California state administrative code which is so wild, and to this day they're still in use, and they're still wasting. So I I think a lot about that. Can I check time, too?

Bert: It's 1:22. And we were already way over time. That's not your fault. We all share that. But it's crip time. It happens every year. So I really appreciate, by the way, that extra history about the short handled hoe. Did you want to stop there? Did you want to add anything?

CIELO: No, I can stop here. I think you did a great job on the website. I just wanted to look at my prior work. But yeah, yeah, thank you so much. Everybody.

Bert: Fantastic. Thank you very much, Cielo, and thank you everybody. If people have thoughts and questions, now is a great time to throw them in. Yes, applause, too. By all means throw in your reactions and appreciation. I have lots myself. If anybody has, I know there was a question for Joselia much earlier, but I would kind of like to offer the opportunity for general conversation for everybody, and maybe start with the artists. If any artists have questions for other artists, or comments for other artists. And see what happens with that. The room is pretty much empty. We have people coming into like grab food. The Zoom room is pretty full, so if folks want to throw things into the chat. I'll look at those. But do any of the artists have comments or thoughts for each other?

Dominic: I just wanted to say thank you to all the other artists, and Bert, for organizing this. I will. I was expecting to talk about my work, but I wasn't expecting to take a whole page of notes from all the other artists. So you inspired the hell out of me today. So thank you for that.

Bert: Oh, yeah, I mean, thank everybody. I'm so happy. This always is like a high point of my year, honestly, getting to hear everybody at the same time, it's peak, off the charts, in the red. Any other thoughts from artists? I have kind of a general observation, and to see if and don’t feel obliged to stay, if including artists, if people need to cut out, take care of life, or the body, or whatever it might be. But my general observation is that everyone who we were lucky enough to hear from today does work about, I think this is what Joselia said, about bodies in space, there's just a lot-- everything from motion capture, to Dominic actually occupying public space, there's all forms of how bodies, and specifically disabled or impaired or debilitated bodies exist or are erased in space. And then there's the very specific aspect of medical paraphernalia, which kind of pervades a lot of the work, and those 2 things relate frequently, I think, throughout all of these artists. Does anybody see any cool connections, in the audience or on the panel here, between how either medical equipment, physical artifacts, and/or forms of being in space, like things you would admire or noticed, or things that resonate?

Darrin: It looks like Serena has her hand up.

Bert: Oh, by the way, I stink at seeing hands either in a classroom or on Zoom, so hopefully, you don't need me to unmute you. Please just speak up. Anybody who has a question.

Serena Jve: Yeah, this is Serena. I have a question, but I didn't want to interrupt your question, so I want to give that space before I ask one.

Bert: I'm not hearing any immediate responses to my vague provocation. So, Serena, please state your question.

Serena: Sure. Hey, everyone! This is such a lovely lecture today. I really enjoyed it.

I am a curator and an artist currently based in Chicago, but have worked a lot of time in LA and the Bay Area. So I was really enjoying seeing some work that I've had the opportunity to see in person. I curate specifically for a project called Spacor that interrogates wellness capitalism amongst global illness, and it's a whole fun thing. But one of the things that we decided in creating this project is that we would only exhibit in ADA accessible spaces, and something that we've come across is that the majority of spaces that we have access to like, we're not at a place with this practice that we can get like museums, for example, that by the legal ADA definition have to be accessible. So within Chicago there's this really great ecosystem of home galleries or artist-run spaces. And I would say, maybe 2% of them just happen to be accessible. And maybe they're not ADA accessible, but they happen on the first floor. And I am in the process of trying to figure out if, as an artist and fabricator, if maybe there should be some type of nonprofit institutional entity to help assist in making spaces more accessible, because I really do believe that it's maybe ignorance or just money, or like people just don't know how to make that. And I'm just curious with this really amazing group of artists that work within the disability spectrum, that are disabled, if you guys know of anything like that, or your thoughts about it.

Mae: Yeah, I have a thought. I don't necessarily know of anything that you're speaking to. Also, this is Mae speaking, by the way. But I think in relationship to your question, a lot of things that are coming up for me are about how the confluence of the fact that the museums that have the funding are also being funded by Zionist and war profiteers, right? And so there's this really hard edge of the ways in which, and like Puar talks about this a lot in “The Right to Maim”, for example, how this confluence of the weaponization of disability or of the ADA with funding that is also literally funding to kill people. And so I think it becomes really complicated, cause on one hand, I'm like, yeah, I want to be able to be at all these shows or have access to these galleries, as someone who's in a wheelchair. And, on the other hand, I don't really want my work up in a place that also has funders who are funding the genocide of Palestinian people, for example, or funding the creation of like war planes. And so I think even this question brings to the forefront these complications that are coexisting around these concerns of access, and usually the people who have most money to do the funding are the same people who are killing other people. So it's just like, yeah, something that I wanted to add to the room? Not necessarily an answer to question, say.

CIELO: Absolutely, and I think the follow up, Mae, I think it's really like you're saying there's apartment galleries, there are things like that. But I think what it really is calling to is kind of the building of alternative infrastructure for our own work, and the kind of deep community building that needs to be done, because as we work with different institutions, and as we kind of glean on the ADA, which I mean is a incomplete and kind of, and oftentimes a violent set of legislation that doesn't really address the real needs of our community. And I think, as we like get deeper and deeper into what it means to make work as disabled conceptual artists, we're going to have better language for our need. And I think this is also part of my work that I didn't get to speak about. But I think a re-formulation of our ethics, I guess I'm gonna say something controversial: away from care and into need. So what are the actual material conditions of our lives? And a lot of it is like. what are the places in which we can share our work in ethical ways that boost each other up, but also keep us in critical and rigorous conversation with not only our work, but also a larger art historical context? So it is really difficult. I mean, I've had friends boycott, my friend Jackie boycotts shows that are inaccessible all the time in LA. And that's one way that we can create work as a kind of resistance. But we can also, I don't know, create digital spaces for each other. I don't. Yeah, if anybody else wants to say anything.

Joselia: This is Joselia speaking. I agree with all the aforementioned. I hope you can hear me. I agree with all of the aforementioned. I'd also like to add that access is constantly transforming. Like the space is not static, and the need is not static, and I really agree with the desire and the proposition of saying like, hey, no more care. What do we need? I think this also will change our audiences. Something that I didn't say as part of my practice is that I started drawing when I was like, I don't know, thirty. Very shortly after my thirtieth birthday, I was hospitalized for a sickle cell crisis. I came out and I started drawing, using materials from the dollar store, and I did crits at the bodega. I'd go to the bodega, I'd see my guy Mo, I'd see the folks that came to the bodega, and we'd talk art. And I think that, like the idea that art is limited to institutions, or something official or something, that we can put on a CV or résumé, really escapes the dire need of the people. I'm only interested truthfully in the need of people, and that means that if the art show is happening at the local restaurant and everybody gets a meal, you know, everybody has somewhere to sit. Somebody got somewhere to lay down, go to the bathroom, they can enter. That is the work. If it's happening in a parking lot, that's the work. And the work is fundamentally, like as we're talking, about geopolitical configurations, right? I think a question that we're bringing up that a lot of people are contending with right now is like, who is living to die, and who is holding death as this kind of thing to defend, as opposed to who is practicing life? And I think access is a practice of life fundamentally. So I just have to say that.

Bert: That was extremely deep, being very sincere. And I was thinking, oh, I'll ask Joselia. Nobody else says anything about the art coming to you? Because that was the question in the chat about the Finnegan Shannon show, and that was a much more capacious, but also resonating with the other folks who spoke with Mae and Cielo, the idea of art coming to you what that could actually look like, and/or feel like, in relation. And yeah, there's so much to say about the ADA as a poor metric, and institutions as the arbiter of what disability is and what art is, and what care is, like care is obviously an economic category. And that's one of many reasons to talk about it. There’s some piece, book or article out that I should look at. I think it's a book, about “Care as the Last Stage of Capitalism.” And I think this, the emphasis on need and access, and art being a project to look out for people is really meaningful, and takes everything to another level that is really exciting.

Ariella: Hey, Serena, I don't know if you're familiar with the Chicago Artists with Disabilities. Facebook group page, they're always like putting out suggestions. And just, you know, resources on there. And it's direct community support. So that might be helpful.

Bert: The Facebook page, Chicago Artists with Disabilities.

Ariella: Yeah.

Bert: Yeah.

Serena Jve: Oh, no. I was just gonna say, yeah, thanks for that. We we're in contact with them. It's yeah, I think, sorry if I framed my question a little weirdly, I think what I was trying to ask was simply if anyone knew of any type of organizations that helped make more alternative non-museum spaces accessible. and that we're thinking of doing that as kind of a side project, of like actually helping build and make the infrastructure to make the physical accessibility to these non-institutionalized spaces.

Ariella: Also I would maybe consider reaching out to 3Arts. They do a really good job at just investing in disabled artists and disabled initiatives. And also there's another grant called the Neighborhood Access Program that's literally striving to promote and bring forth resources to create accessible arts and cultural programming.

Bert: That's really helpful. Thank you for actually coming up with some concrete ideas. I had missed that Serena was in Chicago. So that's a really good thing to imagine happening like, imagine all these small spaces and groups doing more to welcome and support disabled artists and disabled people who want to be in connection with art. Are there any more thoughts or questions, or for people wanting to riff on some of the themes that came up, and that kind of unexpectedly rich question or just, I think, ask questions for recommendations. Let me see. Matt was on the call, who is working on a live stream for them to make open source, accessible gallery spaces.