Dominic Quagliozzi: Medical history

- Bert Stabler

- Jun 15, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 22, 2025

Dominic Quagliozzi, Urban Light IV Pole, 2012. Performance view.

At 11:00 AM on December 11, 2012, the artist Dominic Quagliozzi repurposed an installation of decommissioned streetlamp poles by hanging an IV from one of the poles, in order to administer a scheduled 30-minute infusion of Tobramycin for his chronic lung infection. Entitled Urban Light IV Pole, Quagliozzi’s title is based on Urban Light, a highly visible 2008 public outdoor installation of 202 reclaimed lightpoles at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Urban Light was created by the multifaceted artist Chris Burden, best known for his provocative performances in the 1970s. The most notorious of Burden’s performances include Shoot, from 1971, in which Burden was deliberately shot with a gun in the arm at close range, having himself confined for Five Day Locker Piece, also in 1971, being electrocuted in Doorway to Heaven, from 1973, and 1974’s Trans-Fixed, in which the artist was crucified on a Volkswagen Beetle. Unlike these, Quagliozzi’s performance was an anti-performance of sorts. While it did involve physically embodied vulnerability and suffering, he performed a medically necessary task that was only unusual in its location, not in its execution.

Urban Light IV Pole somewhat echoes Arte Útil, Cuban social practice artist Tania Bruegera’s 2010 gesture of taking an appliance that was identical in appearance to Marcel Duchamp’s landmark 1917 piece Fountain, signing it “R. Mutt,” and installing it in a bathroom at the Queens Museum as an operating urinal; this was the founding gesture of Bruegera’s eponymously-titled project to champion social utility in art. But while both Bruegera’s and Quagliozzi’s works presented mundane functionality in order to refamiliarize, desanitize, and deflate iconic readymades by white male avant-garde artists, Quagliozzi was not marking a visual manifesto. Rather, he signaled an affinity with Burden, an artist who, while apparently able-bodied, performed actions that were injurious to his body and apparently indicative, to many spectators, of a mental injury. Quagliozzi told me that a political statement “never seems to be my main goal.” “My main goal,” he said, “usually is, how can I communicate this idea or concept (so) that other people can feel somewhat (like) what I felt, or can relate somehow, how I felt, or (how) can I put them into that psychic space, or that emotional state?”

Hospital Show, 2013, performance and installation view

The pioneering masochistic performer most readily associated with Quagliozzi, however, is Bob Flanagan, a Los-Angeles-based artist, who like Quagliozzi lived with cystic fibrosis, a severe genetic condition affecting the lungs and other organs. Flanagan in fact called himself a “supermasochist,” and BDSM exploits were central to his spectacular performances. Quagliozzi admires Flanagan, and did at one point take part in a project with Flanagan’s partner and collaborator, Sheree Rose. “But for me,” Quagliozzi said, comparing himself to Flanagan, “I was never that theatrical.” Quagliozzi reflected that “the poetry that (Flanagan) wrote was more of what I connected with. Those kind of like personal moments that he would share and articulate so profoundly, things that kind of led me to... doing my treatments in public, performing sickness. Because CF is an invisible illness and nobody ever really saw that part of me, because I would recluse into the hospital and disappear for two weeks for treatment.” Underscoring this point was Hospital Show, a 2013 public exhibition of works on paper and a video projection in Quagliozzi’s hospital room at USC’s Keck Medical Center. This event was another deflationary social action, in this case related to Visiting Hours, a lavish 1994 performance installation that Flanagan and Rose staged at both the Santa Monica Museum of Art and the New Museum, with Flanagan on site but confined to his hospital bed.

Medical History Pt. 2, 2014, performance view

Quagliozzi has done many performances in relation to his medical treatment, both live and recorded, in hospital settings and in public spaces. Indeed, these pieces tend to convey a stoic whimsy, rather than a profound or exuberant dramatic intensity. Interestingly, two of his most theatrical performances exemplify this deliberately understated character in his work. In 2014 and in 2022 he presented two performances in response to his lung transplant, one before and one after the operation—however, the “after” performance came eight years before the “before.” In 2014, Quagliozzi was on the transplant waiting list. While he felt extremely weak and unable to make artwork, he was offered the opportunity to do a performance at RAID Projects in Los Angeles. For Medical History, Pt. 2, he sat in a chair in a gallery for about an hour, without aid from his oxygen tank for part of the performance. A makeup artist created artificial scars on his chest, using silicone and makeup to visualize how his chest might appear after his transplant, while a video camera allowed the audience to have a view of the “procedure.” Not long after this performance, Quagliozzi did get the transplant, which, despite complications, has resulted in the extension of his life, as well as an improved quality of life. For years after his transplant he sustained the intention of creating Medical History, Pt. 1 as a reconstruction of his body before surgery. Finally last year, the art history program at Wheaton College in Massachusetts invited Quagliozzi in as a guest speaker. He took this as an opportunity to approximate the appearance of his body pre-transplant, again with the assistance of a makeup artist. With special effects makeup, the makeup artist effectively erased his scars, which ironically ended up being in a different place and shape than he had anticipated in 2014. A focus of the concluding chapter in what he calls his “performance diptych” was Quagliozzi’s sternum, since that was where surgeons had to enter his chest cavity because of scar tissue around his lungs.

Medical History Pt. 1, 2022, performance view

These descriptions of Quagliozzi’s videos and performances are not meant to diminish his decades of object-making, but simply to put them in context. While less straightforwardly referential, his physical works, like his performances and videos, make use of medical materials and imagery, they are frequently time-based and/or interactive, and there are always allusions to the artist’s de- and re-constructed body. His recent Fragility Drawings are a recent series of largely abstract and text works that apply graphite and stitching to medical exam table paper, the latter being a material Quagliozzi has sat upon innumerable times. The pieces are displayed hanging from magnets, allowing them to move in the air currents created by viewers’ movements.

Drawings aren't meant to hurt, graphite and white thread on clinic table tissue paper, 2022

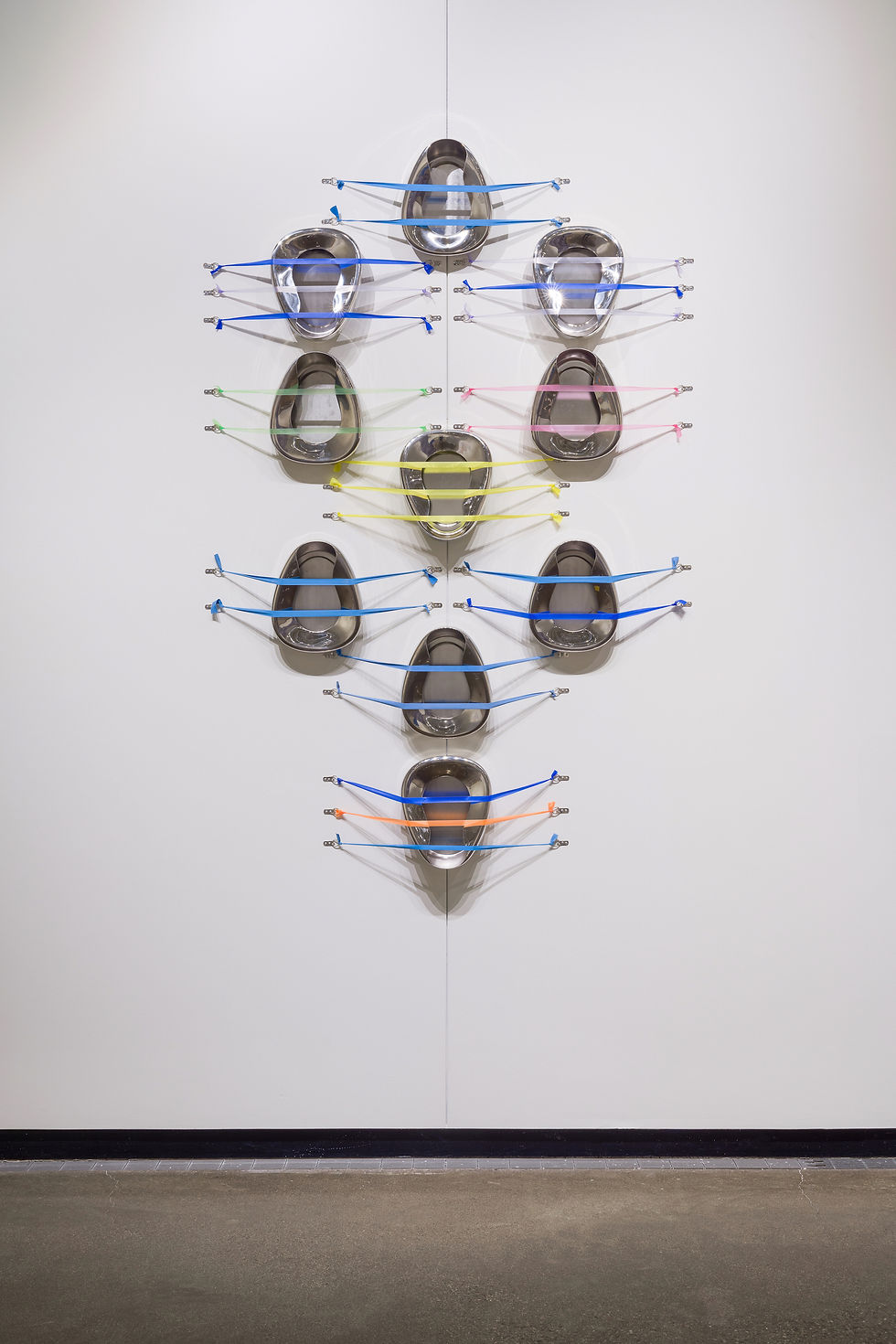

Reminiscent of Bichos, Lygia Clark’s 1960-66 series of hinged metal sculptures, Quagliozzi’s Transformers series from last year comprises modular units of hinged wood blocks wrapped in medical gown material. The pieces hang on the wall, and viewers are invited to arrange them in whatever formation they choose. Medical gown material is also the basis for Suit (2019), a tailored blazer and pants he made from his used hospital gowns and wears for speaking engagements, as well as for Flag (Medicare for All), also from 2019, a gown-based American flag whose statement is summed up in the title. A less recent work, Google 65 Roses from 2011, is a collection of 65 blue balloons hanging from the ceiling, a piece that evokes hospital room décor, or simply lungs. The work is intended to literally deflate over time, and, as Quagliozzi notes on his website, “The piece extends if/when the viewer literally Googles ’65 Roses.’” Quagliozzi has moved now into making mixed-media wall collages, in which the assemblages re-enact the literal stitching of his body, but also the constant logistical management required to handle his shifting impairments and symptoms.

"Transformers" sculpture series on display in "Script/Rescript" exhibition at San Diego State University, 2022

From left:

Transformer (Butter Sticks), wood, hardware, and hospital gowns (state 1), 2022

Transformer (Butter Sticks), wood, hardware, and hospital gowns (state 2), 2022

Rather than making general statements, Quagliozzi asserts that his approach to making art is rooted in communicating his personal experience through a sense of the familiar, thereby introducing a framework to understand experiences for which language is insufficient. “I don't really get into institutional critique as much, like critiquing the medical system,” he reflected. “I think I'm better suited to a one-to-one relationship and somebody seeing my work, and maybe having a personal feeling, rather than, you know, ‘Big Pharma is exploiting patients because prices are too high’-- I don't even know where I would make a comment on that.” But, like Bruegera, he does want his art to have a concrete impact in the world. He works with medical students through lectures and workshops, and he has also been thinking about how he can help other chronically ill people. He told me, “One of the things I've been thinking about a lot is the power of narrative medicine, and being able to tell a very nuanced personal story, and how that can affect your reception from your medical team… not that people should have to care about you to give you good care, but we're social beings, and that can help.”

From left:

Suit, used hospital gowns, 2019

Flag (Medicare For All), worn hospital gowns and thread, 2019

In the end, Quagliozzi’s work is about interdependence—not only at the level of individuals within communities, but also at the level of institutions. His work traces a troubling of boundaries between the medical and social models of disability, an understanding that he wants to impart to his wider audience. “(With) COVID… there’s now so many more… things that non-sick people, non-disabled, people can talk about, masks and isolation gowns, and they can talk about vaccines, and having blood work, and having to rely on testing to figure out what their body is doing, these kind of sensations that are part of my life,” he explained. “I have to rely on breathing tests to tell me how my body is doing. I need a third party to help me with that stuff… Unfortunately, disabled people and chronically ill people have an attachment to institutions and some systems that able-bodied people don't have. And so my work points that out.”

Two states of Google 65 Roses ("Day 1,"left, and "Day 30," right), balloons and thread, 2011

Postscript: I meant to note that Dominic, with other transplant recipient artists in the collective Creative Hybrids Lab, have a show in Australia that is up through fall of 2023.

Comments