Em Kettner: Sickbeds, stragglers, and supplicants

- Bert Stabler

- Mar 5, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2023

The Golden Spokes (autumn wheelchair), 2022,5 x 4.25 x 3.5”, cotton and silk woven around glazed porcelain

The Straggler, 2022, 2.5 x 10.5 x 4” The Eternal Worm, 2022, 4 x 7 x 1”

(With wood surface, dimensions variable; (With wood surface/supports: 4 x 12 x 10”) ,

roughly: 4 x ~15 x 8”), cotton + silk woven cotton + silk woven around glazed porcelain,

around glazed porcelain, on oil-sealed ash

on oil-sealed ash

Em Kettner:

In my recent solo exhibitions, multiple figures have shared a kind of theatrical space, frozen in positions where they chase, guard, and gesture toward one another -- all while smiling and trading knowing, mischievous glances. The accompanying illustrative tiles offer clues into the sculptures’ potential origins: variously depicting characters performing on stage, under study in clinical settings, and merging together in sex, birth, and sickbeds. (…) I install work at a height that prioritizes people who are seated or using wheelchairs. Ideally any visitor will feel compelled to contort or bend down to engage with the work. All of this is my critique against standard hanging height, which privileges people who are over 4 ft and can walk up to an object hung at their eye-level (midpoint at ~ 57 inches). I also like embedding tiles high above anyone’s eye-line as to make them completely inaccessible, and then again at various low spots in the walls or pedestals. These decisions serve as rewards for a viewer who moves slowly through the space, willing to carefully consider the dis- and enabling facets of our environment.

From top to bottom:

Night Shift, 2022, 5.5 x 8.5 x 0.5”, glazed porcelain tile embedded in oil-sealed black walnut

Bright Lights, 2022, 10.5 x 5.5 x 0.5", glazed porcelain tile embedded in oil-sealed black walnut

Grand Finale, 2022, 7.25 x 10 x 0.5”, glazed porcelain tile embedded in oil-sealed mahogany

Bert Stabler:

While taking part in an event commemorating the life and work of 16th-century painter Hieronymus Bosch, disabled choreographer Claire Cunningham says she was “shown a sheet of sketches of beggars and cripples … all the beggars are cripples, all the cripples are beggars … as beggars and minstrels were the only way of surviving [for the disabled].” In her 2016 performance Give Me A Reason to Live, featured in the current Berlin exhibition “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer,” Cunningham poses the question, “what is it like to be pushed down? When is a bent-over posture representative of oppression, and when is it penitent, which would be seen as a good thing in a Christian context?” Moving from past allegories to fantasies of the future, Russell Hoban’s post-apocalyptic 1980 novel Riddley Walker, by contrast, depicts a neo-medieval world in which disabled characters are persecuted, but are also storytellers and revolutionaries who share empathic connections with animals and puppets. And both of these have an echo in the faintly magical descriptions the queer disabled theorist Mel Y. Chen gives in their 2012 book Animacies, wherein Chen poetically describes their intimate relationship with a couch as a source of comfort and support, as well as an extension of their romantic partner.

The Swingers, 2021, 8 x 5.5 x 3”, cotton and silk woven onto glazed porcelain

The Lemon Drop Dream, 2021, 3.5 x 2.5 x 5”, The Comedians’ Bed, 2022, 5 x 10 x 12",

cotton and silk woven onto glazed porcelain cotton and silk woven onto glazed porcelain

The surreal spiritual atmospherics linking the pre-, mid-, and post-industrial worlds depicted by Bosch, Chen, and Hoban is present in the work of disabled artist Em Kettner. Her tiny sculptures employ beautifully and painstakingly crafted woven coverings for fanciful ceramic characters fused with the beds, stairs, ramps, railings, and wheelchairs that support them, as well as with each other, while her cartoon drawings whimsically and salaciously depict exploitive spectacles, such as freakshows featuring snails, and medical theaters packed full of identical doctors with glowing head mirrors. Describing her sculptures as made in reference to small “ritual and votive objects: those collected and carried by pilgrims, saints, and children; those used in healing or transformation ceremonies; and those with covert or lost purposes,” or which “represented pleas for relief from pain, illness, or deformity,” Kettner muses that “at this miniature scale, the facts of the object’s making are on full display even if its utility is lost to time.”

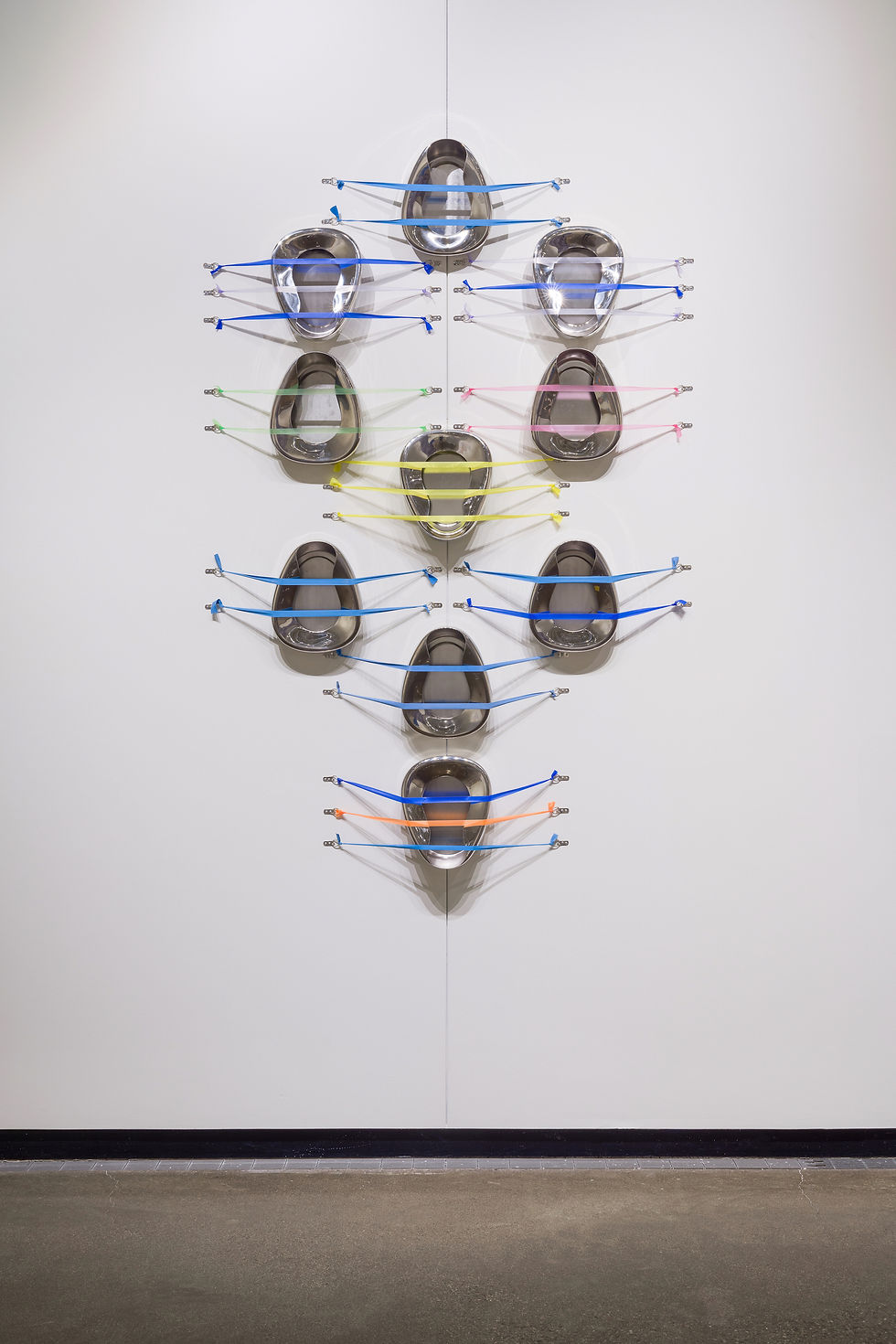

Installation image of solo exhibition “Slow Poke” at Francois Ghebaly, LA

Even given the diminutive intimacy of Kettner’s works, which exude delicacy and defenselessness, the hybridity they evince between multiple humans, animals, and objects conveys a sense of a larger hidden world, in which vulnerable beings are sustained by mutual support, tenderness, ingenuity, and love. In its origins, however, this reinforced fragility was literal as well as conceptual. Kettner shared that “a few years back the clay figures used to melt and break a lot in my old manual kiln.” “When this happened,” she said, “I was more inclined to figure out how to use the parts rather than throw them away-- the sculptures all had faces and limbs and personalities after all.” And this offered new options. She told me that “it was exciting to find I could keep adding to and amending a piece even after it’d been ossified in the kiln.” And the intimacy of these pieces stems not only from their meticulous level of craft, with minute coverings woven directly on to every structure, but also Kettner’s own physical disability, which affects speed and mobility. “I’m able to hold and maneuver the piece while I sew on it,” she said, “using my body as a sort of scaffold to cradle the work as I turn it around and around in my lap, weaving the coverings for the limbs one line of thread at a time.” The coverings are exuberant in their intricate filigree, but Kettner reports also “finding parallels in medical responses to injury or anomaly: binding the body in casts; confining the body to bed; or merging the body with a caregiver, assistive device, or support animal.”

The Supplicant, 2022, 5 x 12.5 x 4.5” (On wood base: 6 x 20 x 10”), cotton and silk woven around glazed porcelain, on oil-sealed ash

The Piggyback (Self-Portrait), 2021, 5.75 x 3 x 3.25", The Long Time Travelers, 2022, 4 x 13 x 6”,

cotton and silk woven around glazed porcelain cotton and silk woven around glazed porcelain

Some sculptures are entitled “The Supplicant,” and, as Kettner puts it, “they coyly supplicate themselves to suggest they pose no apparent threat to a viewer; in my opinion this strategy actually entices more people to consider what they have to say.” She emphasizes their erotic and ludic appeal, noting that “many of my sculptures don the flamboyant patterned costumes of jesters, clowns, and sideshow + burlesque performers.” “Not only were these positions historically often held by disabled people,” she says, “but they were also (arguably) empowering roles which celebrated their perceived differences.” The Victorian critic, artist, and educator John Ruskin would likely have appreciated the premodern overtones evoked by the juxtaposition of patient handicraft and fanciful imperfection in Kettner's figurines. And, returning to Claire Cunningham’s question about the Christian connotations of a hunched posture, Kettner’s sculptures might also recall aspects of the devotional handiwork given to disabled individuals considered unfit for productive labor and committed to ecclesiastical care. But imagining her works to be historical artifacts that came about in such a setting only highlights the sculptures’ impious impish idiosyncrasy, which hints at an esoteric and erotic shapeshifting fairy lore rather than describing a defined cosmology.

Installation of The Golden Spokes and The Straggler in a combined scene called The Chase

Installation detail view of The Long Time Travelers on a walnut surface with a trail sanded out behind each leg

While her work partakes in ritual imagery, and can often convey the precision of an illuminated manuscript or a painted mandala, Kettner is not nostalgic for any spiritual or magical worldview. She notes a shared tendency to exclude and condemn disabled bodies in Abrahamic scriptures, European folklore, and Sumerian mythology, among many other traditions. Still, while her works are undoubtedly personal, they also of necessity feel far from individualistic, since so many sculptures suggest conjoined entities, and her drawings depict dramatic interactions of living beings and material objects. Kettner's affinity for storytelling will be foregrounded in an upcoming interactive online experience that she is now working on, in which accessibility software will be required in order to apprehend the full experience. As suggested above, all of her works tend to connote a post-industrial narrative in which not only the prejudices of pre-capitalist cultures but also the modern eugenic abandonment of disabled people are historical curiosities. “(T)hey’re meant to propose a ‘utopian’ interdependent community' she says, "one in which the participants physically rely on each other and on the material components that make up our world."

Comments