Emilie Louise Gossiaux: Working with the dreaming body

- Bert Stabler

- Jan 21, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2023

Emilie Louise Gossiaux, Big Sur Summer 2010

Emilie Louise Gossiaux grew up fully sighted, but lost her vision in a bicycle accident in 2010 when she was an undergraduate art student at Cooper Union in New York. While her expressionistic artworks feature outwardly striking forms, colors, and textures, she creates them by drawing on subjective experiences of memory, imagination, touch, and intuition. This disarticulated, more-than-visual embodiment is captured in her Yale MFA thesis exhibition, “Memory of a Body.” The installation was dominated by Cerulean Wedge, a large, bright blue ramp-like piece. While it suggests a three-dimensional floor sculpture designed by Ellsworth Kelly, the fabric form is filled with memory foam and visitors were invited to interact with and lie on it. For Gossiaux the piece represented not primarily a geometric abstraction, but the haptic experience of going deeper into a body of water as one walks in from the shore, based on her memory of visiting Big Sur in 2010.

Emilie Louise Gossiaux, My Dad's Old Tattoo series, clockwise from top left: Crucifix, Smiley Foot, E.L.G., Smiley Ankle

Foam also formed the interior of a set of isolated, simplified anatomical sections featured in Gossiaux’s thesis show, modeled on tattooed areas of her father’s body. Two arm sections, a foot, and an ankle alternately rested on the ground, stood on a metal pole, or protruded from the wall. For a later show at SculptureCenter, she presented a table with yet more body parts, now displaying not only her father’s tattoos but also her own, and those of her sister; all three individuals bear the initials “E.L.G.,” as well as sharing some tattoos. In all of these pieces the tattoo design was incised into clay that was then glazed and fired, before being filled with expanding foam, colored “outerspace” black. The foam pushed out through the tattoo incision, creating a tactile extrusion while also literalizing Gossiaux’s idea that tattoos are a way of “the inside coming out,” cleverly inverting stodgy presumptions about tattoos masking emotional vulnerability.

Emilie Louise Gossiaux, It's Alright Florence I'm Only Dreaming installation shots. Clockwise from top left, Watermelon with Honeydew, Whole Cantaloupe w/Ant Mound, Installation Shot from Honeydew and Watermelon Corner, and Floor Piece with Shoes and Brace.

In perhaps the dominant theme of her work, human and non-human experience and subjectivity imaginatively mingle. Gossiaux, who has rich visual memories formed in her childhood and adolescence, told me that her dreams are often quite vivid. In the dream that inspired It’s Alright Florence I’m Only Dreaming, a simultaneously enticing and repellent installation she created while in her MFA program, Gossiaux was setting up a still life of fruit, which crashed to the floor when she turned around. In this dream the fallen fruit lay on a white tile floor partially crushed, brightly colored and oozing juice. The mess attracted swarms of insects, and Gossiaux told me that she woke up waving her hands in front of her face to fend them off. To represent this scene in the gallery she created low raised islands of white tile, on which sat brightly colored whole and broken fruit sculptures, cast in glistening, melting sugar glass. The installation was populated by live ants, who built anthills and fed on the sugar-glass fruit, as well as on sugar-glass casts of Gossiaux’s feet and leg brace. The irregularly shaped areas of white tile were arranged such that visitors navigated the space on paths reminiscent of the winding routes of an ant farm. Doing some research on ant behavior, Gossiaux learned that “they can communicate underground through touching each other… through the antennas and through vibrations, and also through smell.” “It’s not so different from my…. perceptions,” she concluded.

Emilie Louise Gossiaux, Alligatorgirl Riot, no. 1 (left), Installation shot of Alligatorgirl Riot no. 1 and Alligatorgirl Riot no. 2 (right)

Imaginative or mythic relationships with animals continue in her more recent work. Growing up in New Orleans across from a slow-moving canal, Gossiaux was familiar with the sight of alligators. But following Hurricane Ida in 2021, while feeling considerable anxiety for her family who were still on the Gulf coast, she began to consider them anew after hearing reports of alligators attacking people stranded on trees and rooftops in her flooded home city. In two energetic crayon and ballpoint drawings from her 2022 exhibition ”Significant Otherness,” Alligatorgirl Riot no. 1 and Alligatorgirl Riot no. 2, alligator-human hybrid beings swirl around a flooded bedroom. In the same exhibition, a sculpture titled Alligatorgirl adopts the same color scheme of a gray body and white legs, now adapted to earthenware ceramic and cold wax medium. Dots of bright yellow oil paint indicate a piercing stare, both on top of the alligator’s head and on a human face within the gaping fanged mouth. The scenes playing out in Louisiana made Gossiaux reflect on the upheaval humans have caused in natural habitats, creating an unsettling juxtaposition of time scales and evincing a sense, perhaps hopeful as well as ominous, of “the animals coming back and… taking over.” “Just looking at them,” she says of alligators, “they look like they’ve been around forever.” While she often works quickly and intuitively, and prefers to work directly with soft, pliable materials, her comment on the ancient aura of alligators alludes to a sense of permanence that she seeks to imbue to the fantastical content and the unfussy forms of both her drawings and her sculptures.

Emilie Louise Gossiaux, True Love Will Find You in the End, mixed media, 2021 (full shot left, portrait closeup, right)

The straight lines and simplified contours of Gossiaux’s alligator hybrids could evoke various references, but the most immediate association for me was with the Egyptian god Sobek, a powerful crocodile deity associated with chaos. Another Egyptian god evoked by her work is the dog-headed Anubis, as much of Gossiaux’s work relates directly to her experiences with her canine guide and companion, London, with whom she has spent many years. Egyptian statuary seems to be a clear reference point for the sculptural pairing True Love Will Find You in the End, in which two simplified standing figures, both mingling elements of dog and human anatomy, hold hands and look into each others’ eyes. The works are made of carved foam covered in gray celluclay, and have the appearance of stone funerary statues intended to ordain eternal companionship. Similar scramblings of dog and human heads, dog teats and human breasts, and dog paws and tails with human hands and feet, occur in several drawings and sculptures in “Significant Otherness.” These include Dreaming Doggirl, a recumbent clay figure that evokes a hybrid sarcophagus, and the loose contour sketches connote hasty hieroglyphics.

Emilie Louise Gossiaux, London Midsummer (left), Dancing With London installation shot (right)

,As implied by the title True Love Will Find You in the End Gossiaux’s works about London are somewhat different than her speculative encounters with ants and alligators. Almost an inversion of the uncanny spectacle of alligators forced into proximity with humans, Gossiaux finds in her connection to London an equally ancient and holistic, but also intimate and joyful experience of interspecies interdependence. London’s most high-profile appearance to date may have been in the major group exhibition “Crip Time,” which closed in 2022 at Frankfurt’s contemporary art museum. In the main atrium, two life-sized dog sculptures, at first glance apparently jumping toward one another, synchronized visually with the leaping rhythm of Deaf artist Christine Sun Kim’s giant wall mural Echo Trap, in which a bouncing black gestural line is augmented by the painted text “hand” and “palm.” Gossiaux’s piece is entitled Dancing With London, and the work depicts her experience of holding London’s paws in her hands in cavorting celebration. In “Significant Otherness,” which also included ceramic renderings of London’s accessories and toys, two drawings entitled London, Midsummer feature three humanoid versions of London dancing around a Maypole, accompanied by trees, sun, and moon. As joyous as they are, these dancing works are tinged with nostalgic melancholy, representing memories of an earlier time in their relationship. London has since grown too old to dance.

Emilie Louise Gossiaux, Arm, Tail, Butthole

Perhaps summing up all of these tendencies in Gossiaux’s work is the drawing Arm, Tail, Butthole, in which energetic marks and bold colors indicate a haptic connection between bodily extremities. An orange human hand grasping but somewhat indistinguishable from a dog’s yellow tail creates a bold diagonal form, visually balanced by the dog’s bright pink anus immediately below. Gossiaux uses a variety of approaches in creating drawings, including a carefully catalogued array of Crayola crayons, drawing on her recollections and associations with different crayon color names, as well as her appreciation of the waxy texture of crayon, recalling the pliable materials that recur throughout her work. She also makes use of a drawing board with a plastic sheet layered over a rubber mat to create tactile impressions of drawn lines, similar not only to her tattoo sculptures but also to a device described by Sigmund Freud as an analogue to memory and the unconscious in his 1924 essay, “A Note Upon ‘The Mystic Writing-Pad’” Speaking of this famous theorist of anuses, myths, and dreams, Gossiaux reported to me having always had a fondness for the unconscious creative potential of so-called blind contour drawings, long before her accident, and she still approaches drawing as an immediate, iterative, and unpredictable medium. As with all of her work, visuality is neither primary nor peripheral, but forms one element of many in an emergent interaction with materials and memories, creating multisensory imaginative traces of the ineffable.

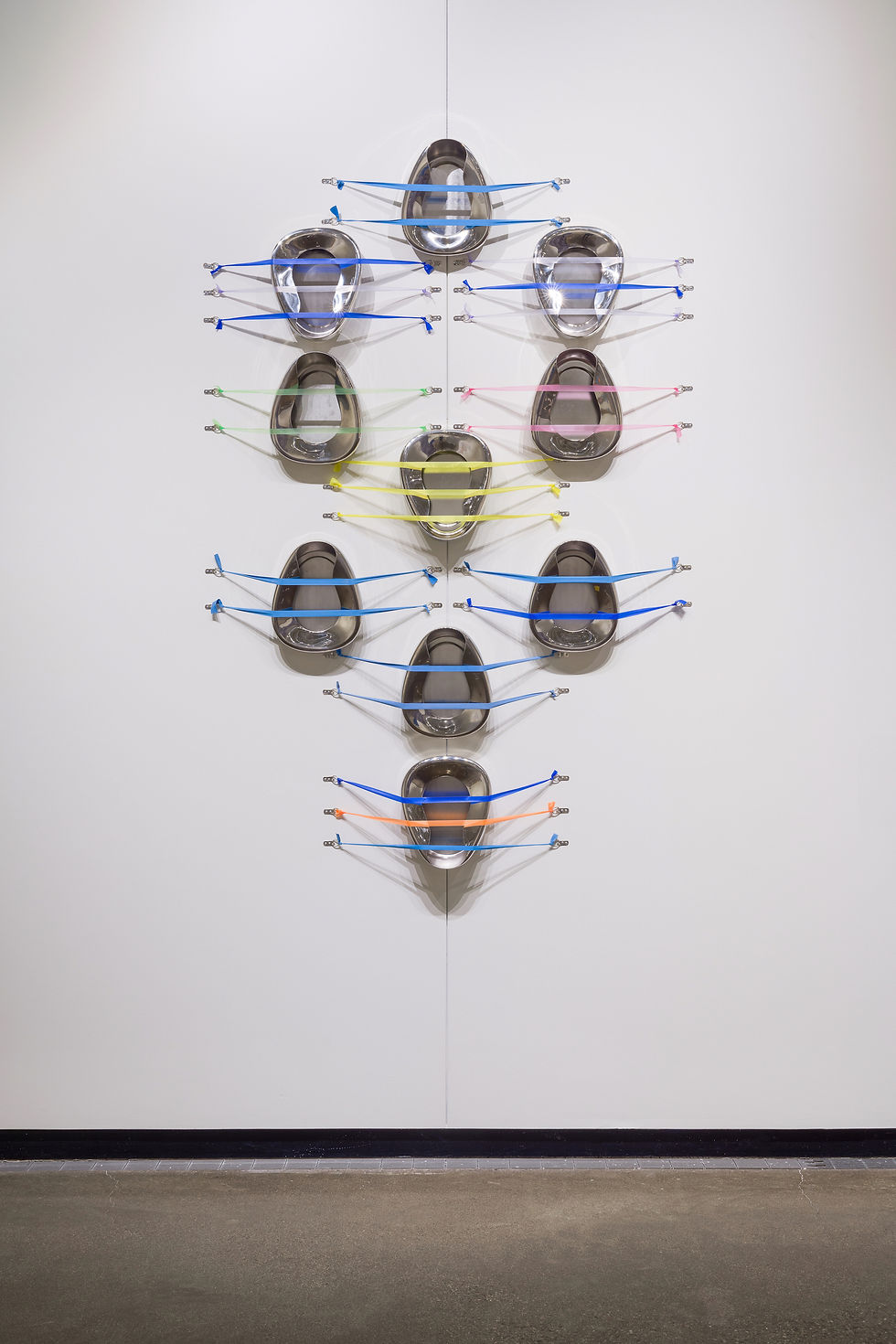

Emilie Louise Gossiaux, Color Journal series, Big Sur Summer 2010 Low Tide Clear Blue Sky Cerulean (left), Stormy Ocean Water My Dad's Old Tattoo Outerspace (right)

Comments