Jennifer Justice: “Who is the person/ whose job it is to remove/ fingerprints from the Brancusis?”

- Bert Stabler

- Jan 6, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2023

In her recent chapter, “Disabled artists, audience, and museum as the place of those who have no part,” legally blind technology artist and scholar Jennifer Justice asks, “If contemporary disabled artists are positioned as vital cultural producers, what is their responsibility (if any) to a dominant cultural milieu that very often restricts or denies access to its spaces?” She brought up the long eugenicist history of museums in conversation with me, noting soberly that “we (disabled people) were specimens in museums.”

In contemplating the consequences of the urgent critique she mobilizes, however, Justice muses that “I depend on art spaces,” and, “nobody’s going to give me a grant to… shit all over art museums.” It is understandable that disabled activists would exercise caution about denouncing institutions, especially when speaking as individuals, since to be disabled usually means to be at least partially dependent, often more so than most non-disabled people, on entities that offer tools and resources for survival, functioning, and flourishing.

Justice’s simultaneous commitment to aesthetic accessibility and ambivalence around adversarial rhetoric is manifested to her recent work with DALL-E 2, an interface created by OpenAI that creates images from text prompts, a process somewhat analogous to the mental work that blind people have to do when interpreting descriptions of visual phenomena. “It's been interesting to follow some of the controversy surrounding AI image generators since I started playing around with DALL-E and DALL-E 2,” she wrote to me. “It's totally reasonable to be concerned about this technology and how it aggregates artists’ data and any user's biometric data, since any input can be manipulated or sold without consent.” Addressing protests raised by those who object to the platform’s unremunerated use of artworks and personal information, Justice said: “I feel like there is less harm in using a dead artist or something in the public domain than referencing a living artist (without their consent or payment). I also want to see how an AI image description generator fares re-describing my described images.”

Pursuing this curiosity, Justice has made use of the DALL-E 2 platform to visually represent a poem she wrote in relation to touching famous artworks, tactile sculpture being a medium she has explored in works such as “Bucket of Rain.” The poem she fed to DALL-E 2 is entitled “Job Description.”

“Who is the person

whose job it is to remove

fingerprints from the Brancusis?”

Justice then altered the poem, in order to see what results the AI would generate.

“Who is the person

whose job it is to remove

The fingerprints from Brancusi’s Golden Bird?”

She then fed the algorithm a description of one AI image generated from her poem:

“Hidden fingers stroke a bulbous gold thumb sitting atop a white desk next to a raven figurine and nonsense plaque.”

Regarding these images, Justice wrote to me, “I kind of like the idea of letting the program cannibalize itself. Instead of uploading my own art, I uploaded one of its own compositions. You can make endless variations from the same generated image.” She explicitly places these experiments in the context of ekphrasis, poems that describe visual scenes and objects, with John Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn” being among the most famous. Tools for translating between sensory modalities, from ASL to screen readers, are at the core of disabled communication and disability culture, but also evocatively deteriorate signification, as AI content generators have amply shown. Far from a mundane fetishization of the glitch, disabled artists like Justice make an appeal to not replace but expand, deform, and rearticulate what Jacques Ranciére, whom Justice cites in her chapter, refers to as a “distribution of the sensible.”

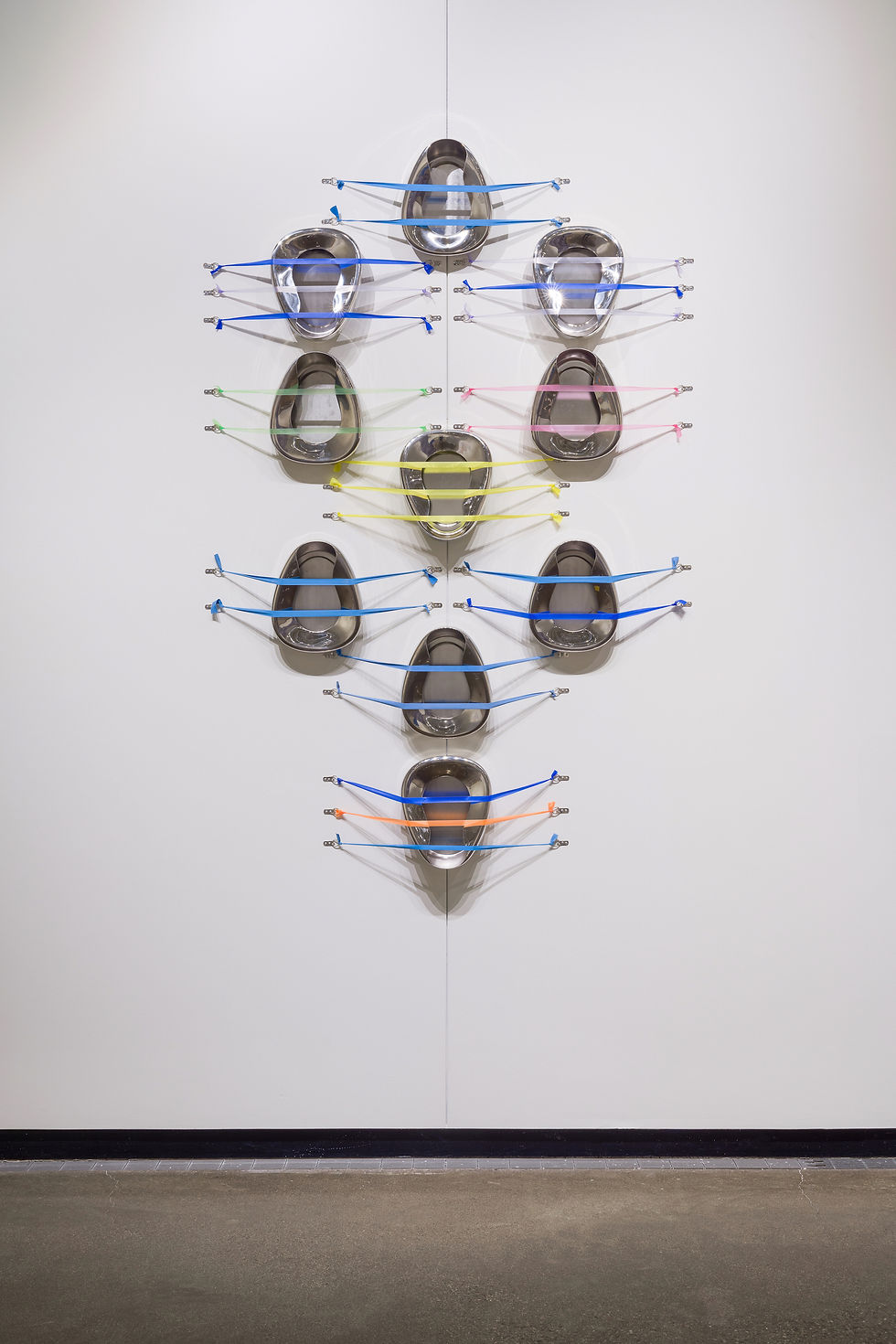

This lack of fixity, precision, and specificity of content or authorship in translations between media in constant networked co-production also hints at an idea of interdependence that is essential to all forms of autonomy in marginal communities, but nowhere more so than in the disabled community. The way in which these intermodal communications echo the vast and miniscule terrains of relation between, among, and within living and non-living matter is represented in Justice’s 2020 multisensory installation, The Foot Knows the Foot When It Touches the Earth, a vivid embodiment of what has been described as “eco-crip theory.”

In this piece, three squat stacks of wooden pallets are loaded with heated earth sprouting an array of mosses, while 3-D printed animal tracks and ambient audio from speakers inside the stacks create a sense of an inhabited world. Viewers are encouraged not only to touch but to sit on and smell these towers. The printed tracks reference agricultural animals like pigs, horses, cows, and sheep. Justice uses tactile transducers to make the stacks vibrate and shake, and additionally inserts a percussive mp3 playlist intended to effectuate the sense of an ongoing stampede.

In works such as these Justice points to the phenomenal world beyond the artwork, encompassing whatever space or platform it inhabits. In 2018 Justice created a “Sonar Cane,” allowing blind sound artist Andy Slater to create an “auditory portrait” of the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, for the project SoVISA Galactic. And with her 2021 tactile map Future Maps, she creates a straightforwardly informational representation of predicted water levels that would result from a proposed dam project. In all of these gestures Justice creates an interface for many senses, which can in turn be an interface for speculation by the viewer on to what a place can be, for a wide range of beings, through a process of conscientious and ongoing interpretation.

Comments