Jessica Karuhanga: "ground and cover me"

- Bert Stabler

- Sep 9, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2023

Jessica Karuhanga is a first-generation Canadian artist from a Ugandan-British family, living with chronic illness. Often strongly informed by an intuitive approach to movement, her works in performance, video, and installation transmit the ineffability of internal states with a strong emphasis on private aspects of Black social life—or, as she has termed it, “Afro-diasporic alterity.” In both live and recorded works there is often a sense that the viewer is witnessing a completely private experience; there may be multiple performers, but they do not speak, make eye contact, or follow any prescribed choreography. The audience appears to be irrelevant. But as Karuhanga poignantly reflected in our conversation, “feeling left out isn’t the same as being left out”—meaning not that everyone can access everything, but rather that the indignation of feeling excluded from an artwork relies on the expectation of being the intended audience for every cultural artifact.

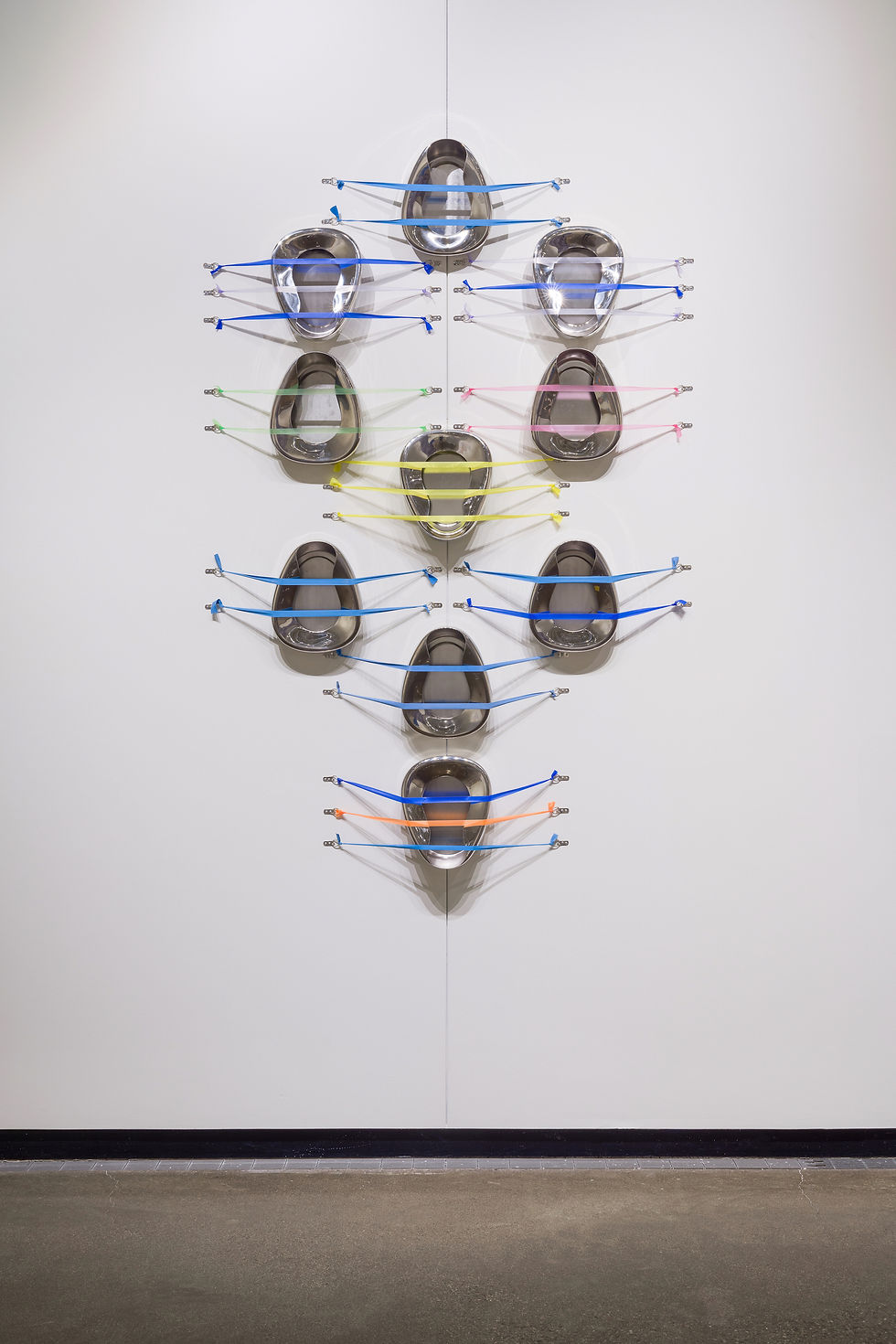

Polyrhythmic percussion, delicately plucked mbira notes, and spells of silence accompany the hand, arm, and full body movements of three young Black women in Moon in the 12th House. In being who you are there is no other, two Black women move freely with their eyes closed among sunlit wild grasses to a serene harmonic vocal soundtrack. Pictured above, from when Karuhanga re-enacted it in Dublin this past May, ground and cover me features the artist wearing headphones, clutching flowers, and caressing the wall while moving through a corridor at the Ontario College of Art and Design. She progresses along a row of windows looking out on to a manicured landscape surrounding the Art Gallery of Ontario, a massive museum which expanded from the manor of an early Toronto oligarch. Sometimes body parts are isolated, as with Karuhanga’s feet stepping rhythmically on loose boards in gold ankle bone cups, or her abdomen, filigreed by her illness, rising and falling in counterpoint to the sound of her breath in body and soul. And a different sort of bodily fragmentation is presented in no other findings, a recording of MRI scans recording the interaction of her body and her illness, appearing to the non-expert viewer as a series of blurry monochrome abstractions.

In all of these pieces, Karuhanga makes use of what she terms, following Katherine McKittrick, “a refusal of legibility" (citing McKittrick's 2020 book, Dear Science and Other Stories). But in our conversation, she also specified that she is not being ”deliberately exclusionary.” Instead, these works make use of obstacles to communication to open up possibilities for interpretation, without allowing the viewer to claim ownership of that explicitly secondhand experience. In the statement for a group exhibition she curated in 2018, entitled Ineffable Blaze, Karuhanga writes of “the exhaustive labours of self-articulation that cast the Black femme subject as dispossessed,” and “defiance of self-defining as a means of actualization.” Echoing the experiences of other BIPOC faculty that are obligated to take on disproportionate amounts of administrative and emotional labor, as well as of other disabled faculty that are obliged to disclose their disabilities, she reflected that the restriction of access she deploys in her art is not something that she has not been able to enact in her frequently precarious employment.

Drawing from her life as a contingent cultural worker, Karuhanga stated that “racialized femmes are targeted.” She talked with me about how she spent well over a decade in temporary teaching positions after receiving her degree, receiving little institutional support while being exposed to the racist, ableist, and ageist assessments of both students and administrators. Her response has been to gather letters of support from colleagues and former students, and to offer support in whatever way she can to students who are shut out of courses and peers who are looking for work, as well as learning from and giving explicit credit to everyone with whom she collaborates.

This ethic of solidarity and care extends to her performances. As an example, in her piece Through a Brass Channel, rather than requiring her collaborators or herself to endure the brutal conditions typical of early feminist performance work, she limited her performers’ shifts to three hours and created a green room area to allow for relief and respite as needed. As she put it, “yes, I collapse the fourth wall, but that doesn’t mean that’s… an invitation to be disrespectful.” In pieces such as ground and cover me, this same desire to feel safety is reflected in the use of headphones; “when you wear headphones in your walk,” she says, “it’s like, ‘don’t speak to me.’” A modern minimal aesthetic of restraint is thus for Karuhanga far less about any implication of austerity, perfection, rigor, or discipline, but more about an openness that is not exposure, a space created on a small scale between people with shared experiences.

-- Bert Stabler

Comments