Jillian Crochet: Handle with care

- Bert Stabler

- Jun 22, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 21, 2024

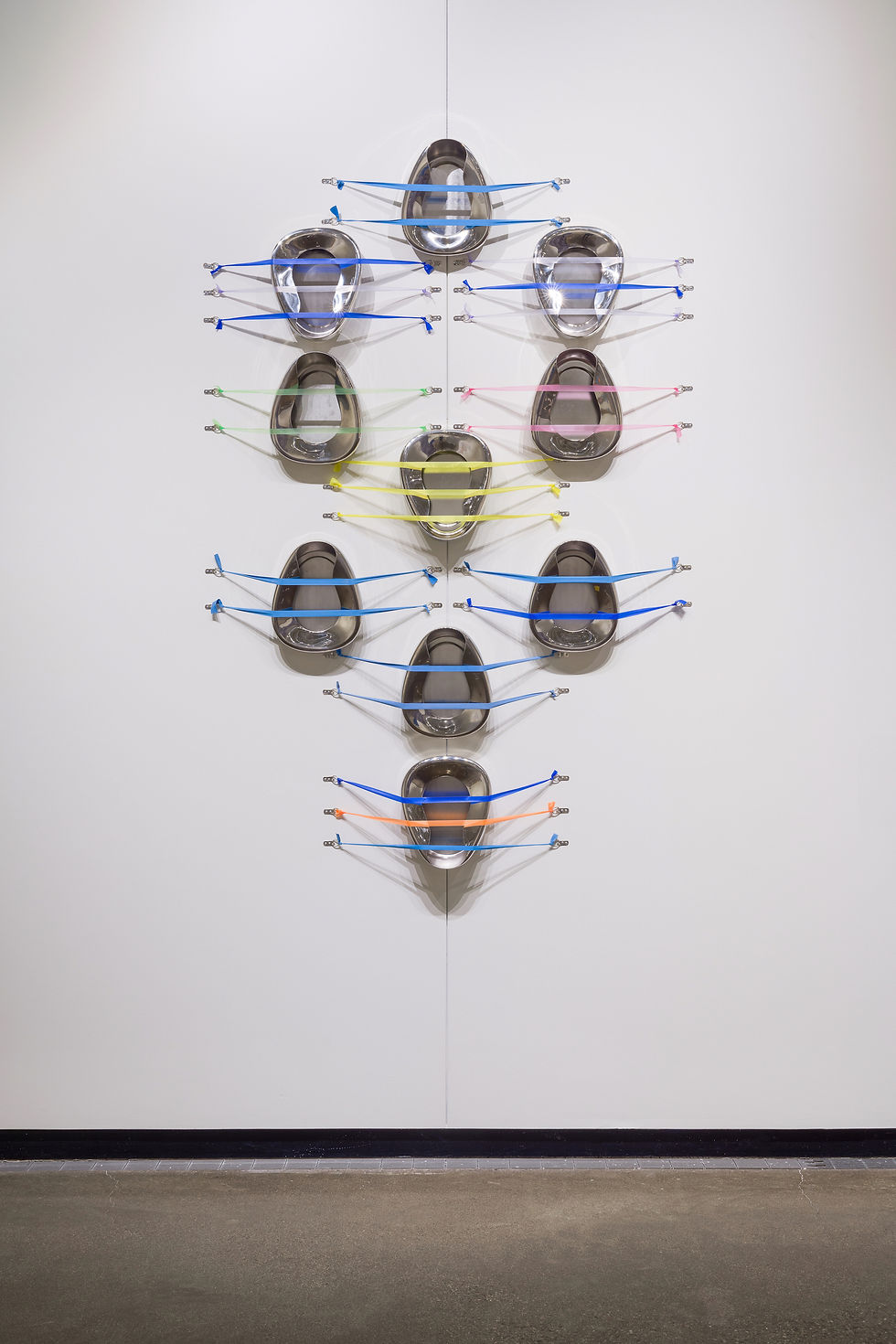

Jillian Crochet, I Like Nature and Nature Likes Me, 2021, installation view, photo by Andria Lo

Occurring in the first year of the COVID pandemic, Jillian Crochet’s year-long residency at the Marin Headlands, just north of San Francisco, was even more isolating than she had expected. Throughout the year, Crochet made several laborious excursions to an open area of the windy coastal prairie, navigating her mobility device over rough ground, carrying camera gear and dragging her mattress pad on a rope lead, all while wearing a furry suit that she had fabricated to resemble a bobcat. She would settle in a chosen spot in hopes of summoning a small bobcat that she had seen skirting the steps of her remote studio early on in her stay. She would stay as long as her stamina would allow, usually for somewhat over half an hour, and then pack up

and go back to her studio. The bobcat never materialized, though Crochet told me that at times she had been asked for directions by hikers, deer were often nearby, and she was once fairly close to a coyote. Eventually she created two pieces from twelve of these excursions, each with six videos composed onto one screen, respectively titled I Like Nature and Nature Likes Me (winter) and I Like Nature and Nature Likes Me (spring). The coyote may have helped to inspire the shared name of these two videos, which alludes to I Like America and America Likes Me, a 1974 performance in which the shamanic German artist Joseph Beuys spent three days in an art gallery wrapped in felt and cohabiting with a coyote, partially as a meditation on the American war in Vietnam. Speaking to Crochet, I speculated that the rope pull for her mattress pad also seemed to reference Beuys’ sled-based works. For her, though, the title was essentially an afterthought. The forays were about her own physical and emotional efforts to connect with the place where she found herself, efforts-born out of many failed attempts to access “nature”.

It's ok, 2019, performance view, photo by Ellyce Moselle

The durational relation to physical space and matter is more intimate and haptic in some of Crochet’s other video performances. Until it’s me (2019) foreshadows the I Like Nature videos, offering a more contained meditation on fabric and endurance, animals and nature. In this video, Crochet kneels in the grass in a dog park, wearing a beige leotard and slowly pushing a small sandbag sewn from shimmery fuchsia velvet, as dogs bark in the distance. The main soundtrack of Grieving Touch (2021) is a verbal description of a field of more velvety moss-green sandbag sculptures (forms she calls “lumpies”), soft masses that her hands, entering the frame, slowly and deliberately grasp, manipulate, and caress. For it’s ok (2020), a camera mounted to her wrist shows her hand gently stroking the spiky leaves of an aloe plant, and murmuring the titular phrase, “it’s okay.”

Rock costume performance (concept sketch), 2023

Crochet described other performances where she communed with houseplants, caressed dandelions, or hugged a fern. A work still in the concept phase is a “rock costume,” inspired by the lumpies, that would fit over both her and her wheelchair. These works simultaneously evoke the understated feminized surrealism of photographer Jeanne Dunning and the ineffable stimming that the autism advocacy blogger Mel Baggs narrates in their remarkable 2007 video, In My Language. At the same time, Crochet’s pieces also convey the prickly, uncanny calm of an ASMR video. These performances all subtly question the devaluation of disabled bodies by troubling distinctions between conscious and unconscious activity, and animate and inanimate matter—or, as Crochet put it in our conversation, “What is natural? Who is natural?”

Resting Rocks, 2022, silk, velvet, and sand, installation view, photo by Impart Photography

Distilling and intensifying these elements of her practice in her one-minute video performance from 2019, Does this feel normal, Crochet uses a doctor’s rubber mallet to rhythmically pound a small, smooth rock, yielding resonant blows. In a statement posted with the video, Crochet writes: “In the medical model, bodies become fragmented scientific experiments- for over a decade, I have been a willing test subject - I repeat the doctor’s uncanny question, ‘Does this feel normal?’ while testing a rock for reflexes, over and over... maybe enlightenment will come with repetition.” Speaking of watching this video in a gallery, she likes when it is “a little bit too loud, echoing throughout the space,” reflecting that the viewer’s experience can go “from uncomfortable to absurd to humor… like a trance, or like a… mantra.” However, in terms of its reception, “people have critiques of it taking up too much space… there has been pushback.”

Visitor instructions for interacting with Resting Rocks. Courtesy the artist and The Contemporary Jewish Museum. drawings by Charlie Lederer

This connects with issues she had while showing a large collection of her soft sewn sandbags, now resembling gray boulders, as an interactive installation entitled Resting Rocks in a 2022 exhibition at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. Some viewers, who were unsure of how to interact with the lumpies, treated them roughly, causing seams to split and sand to spill onto the concrete floor with more frequency than was expected. This caused considerable anxiety for museum authorities, and after a lengthy process of consultation, Crochet compromised to allow carpet to be installed beneath the sandbags, even though the available carpet texture aggravated her tactile hypersensitivity. Both of these experiences have solidified her characterization of the traditional gallery or museum as “a white box (that)…insists on being sterile and void of human touch… silent,” and have reinforced her intention to “not (edit) out the humanness... not (edit) out the messiness” in her work.

The artist mending Resting Rocks, photo by Minoosh Zomorodinia

Directly confronting this cultural preoccupations with silence and cleanliness, a branch of Crochet’s practice that she began developing during her Headlands residency uses public signage as an explicit retort to ableist spatial norms. Named after a 2008 lawsuit filed and settled by the legal nonprofit Disability Rights Advocates, Lori Gray et al vs. Golden Gate National Recreation Area is an altered accessibility map of the Marin Headlands, which form one portion of the massive GGNRA. Crochet affixed 42 handwritten sticky notes to the map, containing comments such as “The park suggests you learn by trial + error” and “They mark trails for dogs, but not for disabled folks.” A version of this work was installed onsite, and she has also made it into a downloadable PDF, featuring links to websites and videos that address specific and general concerns of physical and communication accessibility.

Lori Gray et al vs. Golden Gate National Recreation Area, 2021, installation view, photo by Andria Lo

She originally researched the Gray settlement, hoping it would have specifically required the Headlands Center for the Arts to have an accessible bathroom, but it did not apply. Crochet then had to personally advocate to have one installed, enacting the unreasonable task too often assigned to people with disabilities - to laboriously, and often futilely, insist on compliance with the ADA. When Headlands finally acquiesced and built an accessible bathroom, she placed an artwork label in it identifying her as the artist, the work as "Accessible Bathroom, 2021,” and listing the materials as “Emotional labor, tears and negotiation.” Additionally. Crochet created and installed a sign for a stairway at the Headlands, reading “BUILT AND MAINTAINED FOR CERTAIN BODIES.” Despite her insistence, all of her works and signs were removed, but labels on some artist additions and alterations to the space, including the bathrooms, exist permanently.

Accessible Bathroom, 2021, installation view with detail, photos by Andria Lo

Referring to the backlash she experienced with various works, including Does this feel normal, as well as consternation with her installation at the Jewish Museum, Crochet reflected, “I don’t outright (intend that) this work’s gonna be an issue , or challenge (institutions), but… if I find that I’m giggling to myself,… or if I’m maniacally laughing because it is absurd, then I know something good is happening, but I’m not in that moment saying ‘I’m not following your rules!’… but it’s interesting that… there’s often some part of it that… becomes a problem for the institution.” At most institutions , she recalled “a team of people meet to discuss what to do with me, my body, or my art, ‘troubleshooting,’ disability—it’s a classic example of why disabled people insist on ‘nothing about us without us’..” She continued, “Of course I don’t want to be in a bunch of tedious meetings, but if they’re having meetings, and nobody’s disabled, inherently, although unintentionally, institutional ‘solutions’ are often going to continue being entangled in institutional ableism.” As one response, Crochet said, “I’m intending to work on kind of an access rider or contract, for this work specifically.” But more generally, she interprets the museum’s response to the leaky lumpies as “a regulation of messy bodies, which is a regulation

of disabled bodies.”

Built and Maintained for Certain Bodies, installation view with detail, photos by Andria Lo

In her work and her advocacy, with and without symbolic language, Crochet encounters and articulates the space of disability resistance both within the domain of liability and litigation, and beyond it, in the somatic encounters and overlaps of bodies, objects, and materials. The seams that hold together minds, hearts, and relationships torn by trauma are always in danger of splitting, as are the seams holding together ableist hierarchies of beings. The work of repair, as Crochet emphasizes, is one of emotional labor, of perpetually feminized care work, and this work necessitates unraveling the stability of hierarchies while also sustaining people and communities. In this balance of comfort and conflict, external dialogue and inner experience, pliability and vulnerability do not mean passivity, but can offer a lumpy model for interdependent imperfection.

Resting Rocks Performance, 2023, performance view, photo by Ellyce Moselle

Comments