Joselia Rebekah Hughes: The gravity of slowness

- Bert Stabler

- Aug 4, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 6, 2023

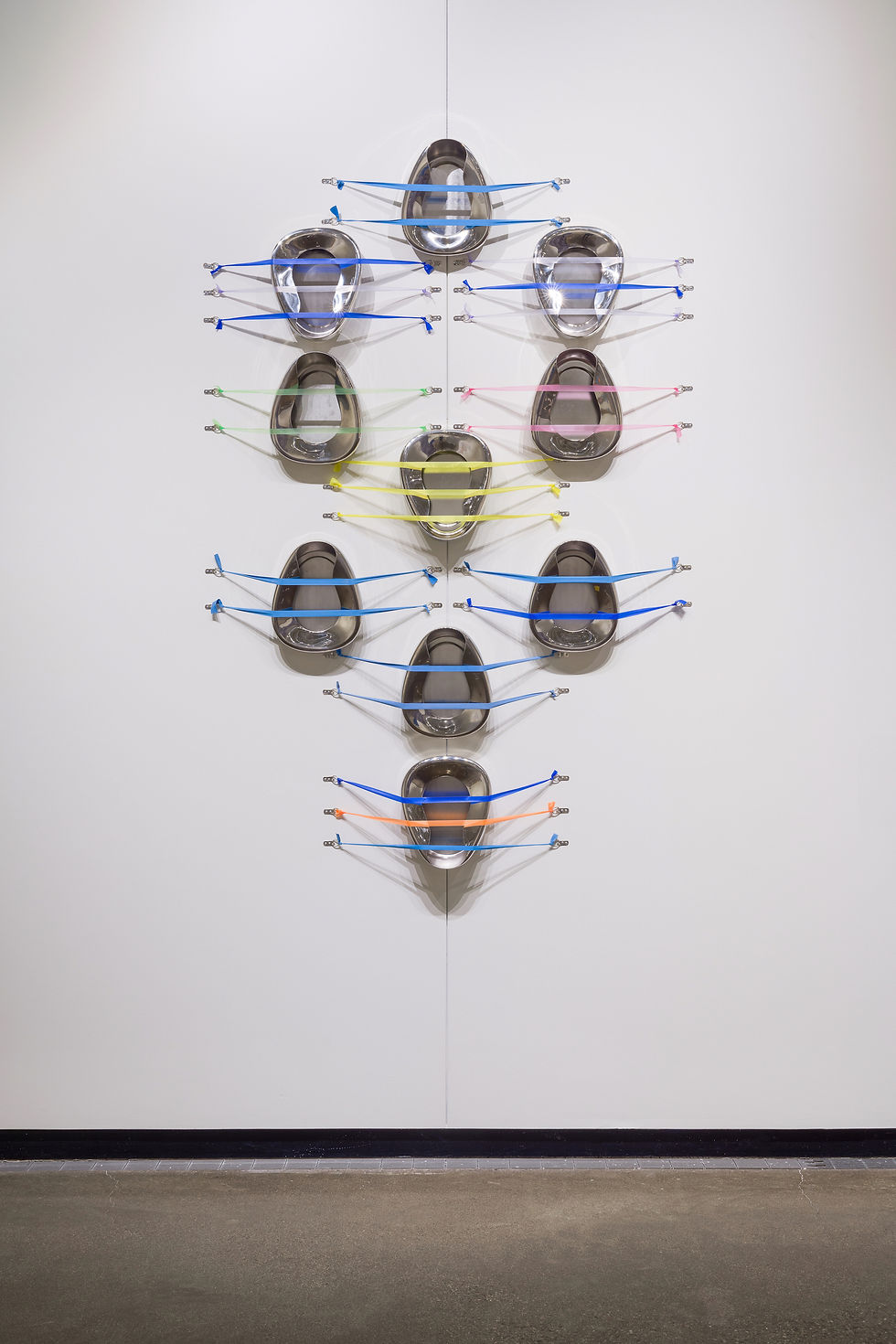

Joselia Rebekah Hughes, Verbena’s Apothecary (2023 interpolation) for/from “Don’t mind if I do,” curated by Finnegan Shannon at MOCA Cleveland until January 7, 2024.

In her 2017 book The Right to Maim, Jasbir Puar describes this eponymous right as the power of the state to deliberately cause injury, to debilitate, and incapacitate on a mass scale. She opposes this “right to maim” to the state’s right simply to give life or take it away, as described by Michel Foucault under the headings of sovereignty and biopolitics, or, later and more expansively by Achille Mbembe as necropolitics. In the U.S., anti-Black racism has been a perennial cause of what Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes as “premature death,” which is in turn a direct outcome of what she terms the “organized abandonment” of BIPOC communities by the state. In the case of Black Americans, who disproportionately endure severe chronic conditions like asthma, diabetes, and heart disease, perhaps no condition more perfectly represents this “right to maim,” as an apparently natural outcome of deliberate brutality and neglect, than that of Sickle Cell Disease, a painful and life-shortening condition mistakenly but popularly associated exclusively with African Americans or, more generally, those racialized as Black.

Writer, editor, educator, and artist Joselia Rebekah Hughes lives with Sickle Cell, and identifies more with Puar’s categories of debility and capacity than with any mainstream concept of disability. She told me, “I think that disability studies, while great, has a very serious problem regarding whiteness as a priori,” whereas Puar’s formulation, she feels, “seems to be far more robust, and has more room for what it is that I'm trying to tie together.” She mused, “I'm really interested in: What does it mean ‘to be able’?”

Delving into etymology, Hughes explains that “the word ‘able’ really just means ‘to hold’.” She continued, “That got me thinking: what does it mean to hold something? What does it mean to be held? Has a hold ever been a physical space? It is a physical space. A hold is the space. Okay? Now we're somewhere interesting, right?” Invoking In The Wake, Christina Sharpe’s powerful 2016 literary reflection on the afterlives of the Middle Passage, Hughes went on: “if we understand the physical space of the hold of the [slave] ship, what happened in the hold? The hold of the ship was, at least in part, a space of ability making. It's the ability [making] of colony. It's the ability [making] of what is human and who is human. It's the ability making of murder and violence and surveillance. It's the ability making of empire, of slavery… and everybody on the ship, regardless of whether or not they were in the hold, are in this process of ability making.”

Untitled drawing, n.d.. Yellow and black gouache on white watercolor paper. Courtesy of the artist.

Hughes’s connotational leap, intuitively linking a consequential but largely unexamined and presumably neutral descriptive word to a foundational and ongoing history of diasporic trauma, seems emblematic of her expressive rhythm of incandescent bursts. “I know this about myself, I am a sprinter,” she says. “I'm gonna run with it. I might not get super duper far, but I'm gonna run with it, and I'm gonna run fast. I'm also a walker. If I do a distance, I have to walk. I can’t run a marathon.” Arseli Dokumaci writes, “I propose that chronic pain is the experience of shrinkage, a diminishing environment(.)” Dokumaci quotes Georges Canguilhem, who describes the experience of disease as “a reduction in the margin of tolerance for the environment’s inconstancies.” Hughes’ wide range of projects, from poetry zines to performance videos and analog/digital paintings, reflect this experience of inconstancy, first sprinting and then walking, employing rapid shifts in mood, format, and perspective.

In reflecting on her use of words, Hughes recalled her heritage. “My family is Jamaican, Cuban, and Guyanese. So, I experienced lots of Rastas, and… if you know anything about the Rastafari movement, there is an acute attention to language and the restructuring of language to reveal power dynamics, which is something I think I've inherited in the way that I use wordplay. For instance, if you're a Rasta, you don't say ‘understand,’ you say ‘overstand.’” Hughes concluded, “These kinds of linguistic maneuvers both expose and validate oppressive forces, and then validate one's own experience within that system of oppression.” At the same time, she reflected, “I like things [I do] to have the gestures of sense, but I'm not beholden to Reason,” and later opining, “I don’t see the mystical as being in contention with science.” This culturally grounded and poetically attuned interrogation of power informs her writings and performances on race and ableism.

Hughes describes “Claudia the Invalid Oracle,” one of her hilarious and incisive characters from Masque On, Hughes’s ongoing series of largely improvised video commentaries, as “me unmasked… this is what I would be doing if I could just have a little space to be myself.” She chose the name “Claudia,” she told me, due to its derivation from Claudius, Roman emperor and father of Nero, who had a limp and deafness due to childhood illness. In one video, the slightly manic seer interprets cards from an Uno deck in the manner of a Tarot reading, and in another she rolls DND dice and makes connections to atomic elements on the periodic table—all while making oblique yet deeply cutting observations on the ignorance and hostility surrounding her. “(Masque On) was initially created to do a simple task,” Hughes said, “create jokes in which debilitated people were not the butt. It was like, how can you be funny without punching down, and to put the tension of where you're punching into question from the very beginning?”

Objects used to “stuff” Verbena’s Apothecary (2023 interpolation) for/from “Don’tmindifIdo”curated by Finnegan Shannon at MOCA Cleveland until January 7, 2024.

Hughes does have a completed major book, which she conceived while recovering from a difficult hospitalization over her thirtieth birthday. Its title, Blackable, is a portmanteau of “Black” and “reasonable” (along with the aforementioned associations with “able”), and she describes its form using another portmanteau, “nopem,” combining “novel” and “poem.” Drawing on a rich history of Black literary bricolage, the work blends formats such as absurdist poetry, confessional entry, limericks, abecedarians, erasure, and short stories. After several misses with other publishers, she plans to release this text on Emily Sara Hurley’s platform Cripple.

Hughes strongly identifies as an autodidact, teaching herself artistic and software skills, and proudly recalled printing and amending content, labeling and stuffing poems into hundreds of pill bottles by hand, as well as stamping text on bags, for her ongoing edition project Verbena’s Apothecary. Commissioned by Nontsikelelo Mutiti and Egbert Vongmalaithong through Institute for Contemporary Art:VCU, a group of artists were asked to make editions in response to Toni Morrison’s speech upon receiving the Nobel Prize in literature, in which the author described the significance of “doing language.” An interpolation of Verbena’s Apothecary appears in Don’t mind if I do a group show organized by artist Finnegan Shannon in conjunction with the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. In this exhibition, seating is placed throughout the space and the artwork is on a conveyor belt, so that “the work comes to you, you don’t have to go to it.”

Working by hand, putting in physical effort, is a commentary on racialized and gendered expectations of labor and leaves what Hughes calls “an energy signature.” Rather than the term “spoons,” commonly used by disabled people to measure fatigue, Hughes invokes “energy jewels,” mingling the connotations both of gems and of joules, a standard scientific measurement of energy, to evoke her alternating experiences of rapid expenditure and “the gravity of slowness.” “I can feel my cells sickle,” she says. “It’s a weird feeling… oxidation and hemolysis make tangible impacts on my body, and I cannot ignore it, even if it feels mystical.” In her proclivity to “run fast not far,” to “sprint ahead and return,” Hughes continually honors the Akan principle of Sankofa, to “go back and fetch it,” a time-honored principle of Black diasporic wisdom and kinship.

Comments