Liza Sylvestre + Christopher Robert Jones: Flashlight Project (excerpt)

- Bert Stabler

- Mar 14, 2022

- 4 min read

Liza Sylvestre + Christopher Robert Jones

Flashlight Project (excerpt)

Video, 15min 22sec

2021

Artists' statement:

This video is an extension of a larger collaborative project titled Flashlight Project [FP] which addresses a need to reconfigure conversations models in order to consider individuals with differing levels of sensory ability. FP is interested in how exploring the intersection of learned systems of body and language disrupts systems of normatively, it questions normative modes of communication design and pays specific attention to the demarcation between the private and social body, one that is predicated upon compulsory able-bodiedness. How are subjectivities shaped by systems of meaning and access? How can they be used to create space for others?

Liza Sylvestre and Christopher Robert Jones are two artists collaborators who are also life partners raising a child together. They have different disabilities between them but the presences of Liza’s deafness within their familial structure is at the core of FP. Through FP they explore how deafness appears within their collective lives and how it complicates notions of interdependence, communication, and sensory ability.

Bert Stabler:

As mentioned above, the video refers to a larger ongoing project by Liza Sylvestre and Christopher Robert Jones, in which they stage group conversations in a darkened space. Participants have flashlights that they shine on their faces while speaking one at a time, following Liza's instructions, in order to ensure that the conversation is accessible to her. In this video clip, Liza and Christopher discuss paradoxical and frustrating aspects of language and communication, not exclusively but especially for people who are D/deaf or hard of hearing. Through overlapping clips of audio dialogue, translated in contrasting-color captions and with intermittent circular spotlight vignettes displaying closeup video footage of walls and surfaces, mouths and eyes, the piece inserts the viewer / listener into a thoughtful and relatable conversation about linguistic accessibility, frequently punctuated by polyvocal aural confusion. In a presentation to my disability-focused art education class, Liza spoke about this piece in the context of a "cripistemology" orientation, which she explicated for us as "what fills up the space of what's missing, the knowledge produced by and around the disabled experience."

Liza is hard of hearing, and makes use of a cochlear implant. In her presentation to my class, she said that with her implant she can hear 16 of the roughly 40,000 pitches a fully-functional human ear can perceive. Media theorist Jonathan Sterne writes about the MP3 digital audio format as part of a long technological "history of compression," a practical genealogy of compact formats of abbreviation running counter to an equally long aspirational "dream of verisimilitude," the ongoing quest for ever-more naturalistic virtual experiences. In specific relation to deafness, this tension between artifice and naturalism can be seen directly in the history of telephony as developed by Alexander Graham Bell. A proponent of early tools for hearing enhancement, Bell was also a believer in eugenics who opposed the teaching of sign language, and asserted that deaf adults shouldn't have children together due to the increased likelihood of having a deaf child. Deaf critical disability scholar Lennard Davis was just such a child of Deaf parents, and Davis has made compelling claims for text as a medium that promotes and privileges cultural practices of deafness through a reliance on visual communication that precludes and excludes speaking and hearing. The erasure of sensory information is frequently not only preferable for purposes of efficiency, but can often be optimal or necessary for effective communication, and Liza's work serves as an extended meditation on the political parameters of these functional limitations.

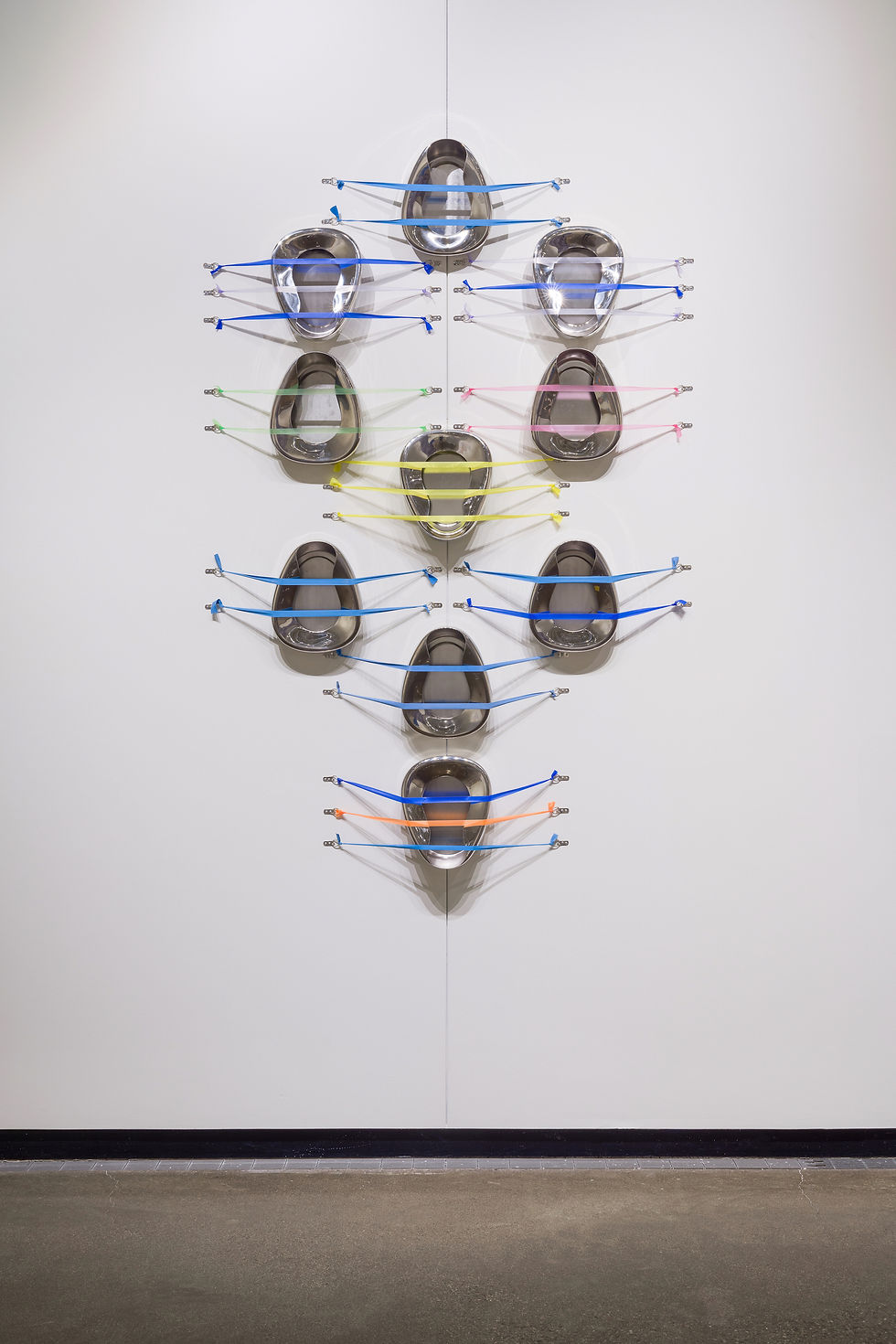

By embodying these exclusions and lapses, Liza's artworks express her aural and visual experience of language, whether through transcribing and redacting text to reflect her hearing constraints, creating interactive audio and video pieces that incorporate her own hearing limitations, or creating video with captions presenting her own critical responses to selected cinematic and animated content, informed by her experience as a deaf viewer. Another installation invited artists to make images based entirely on audio descriptions of visual artworks, originally created for blind visitors to museums and galleries, with odd and eclectic results. In keeping with the spirit of her captioning works, Liza has created pieces that reflect her own subjective forms of communication, inventing a visual guide to her own version of sign language, rendering her experiences of music in shapes and text, and drawing abstractions of visual information, evoking formats from data visualization to musical scores in order to depict what is conveyed in the failure to communicate.

Liza's works demonstrate how in supposedly neutral and open spaces of art and academia, liberal settings allegedly amenable to what Jurgen Habermas terms "communicative action," disabled people are subtly but consistently denied equal standing as autonomous participants. Through appropriating technologies of mediation and commenting on the imperfections of accessibility enhancement, Liza leverages her subjective sensory experiences to make larger points about the social power embedded in these discursive situations. In her artistic cripistemology, disabled people learn from their exclusion through their privileged perceptions of discontinuity, unintelligibility, and erasure.

Comments