agustine zegers / antediluvian accords

- Bert Stabler

- Feb 18

- 6 min read

The bulk of Sensory Experiments: Psychophysics, Race, and the Aesthetics of Feeling is comprised of individual chapters devoted to each of the five senses as they appear in discourses on social distinctions in the early decades of modern consumer culture. In the chapter on scent, author Erica Fretwell cites Hippolyte Dussauce’s 1868 Practical Guide for the Perfumer, wherein Dussauce states that “odors impregnate all bodies”—although, as Fretwell makes clear, what fate a body marked by scent comes to be metaphorically impregnated with depends a great deal on the race, gender, sexuality, and wealth with which it is associated. In their work, the Chilean olfactory artist agustine zegers distills their conceptual investment in scent in relation to both the social and the physical environment, telling me:

There's something about smell and the way that it interacts with our body, that to me is a vibrant portal into thinking about geopolitical violence, thinking about illness as a porosity, thinking about that porosity as a portal into community, and community being expansive in the sense of holding an environmental understanding. There's something about the respiratory that really makes cogent, or makes potent, the degree of intermeshed and transcorporeal relationships we have to forms of large- scale, ecological intervention.

While their fine art work draws on a theoretical lexicon of dynamic potentials and molecular affects, zegers wants their work, at least in part, to bypass language. “The exciting point for me about making work is that it's a kind of theory in action…,” they say, “using the body as a sense-making tool… really expanding bodily intelligence a way to not be in a dissociative relationship to the endless environmental information we receive."

zegers works not only in gallery spaces, but also creates scents for sale under their agar olfactory label, as well as for workshops and other pedagogical projects through their project Speculative Scent Lab; through these projects, they tell me, “people can have experiences at home, and modulate their own environment for engaging with something without having to expose themselves to the environment of an art institution.” In all of these endeavors the smells they design are generally unrelated to active animal and plant life, the distillations of musks and floral essences that were originally combined to create odors that perfumers refer to as “accords”, as well as the synthetic analogues and mutations subsequently developed for mainstream consumption. Rather, zegers seeks to evoke larger timescales of decomposition, with scents evoking yeast, fungus, and soil enzymes, or often conversely the lack of decomposition, in the case of fossil fuel concatenations in the present as well as the far distant future; a y2k-inspired scent they created under agar olfactory promises to evoke “hot fax machine, mouse pad, Mac carcass, and tattered wire”. The allures of poison, fermentation, and rot, pathologized as perversion in a medical condition known as “pica”, offers in zegers’ haunting accords a wordless sensory metaphor for the pleasures of literal longue durée “intoxication”.

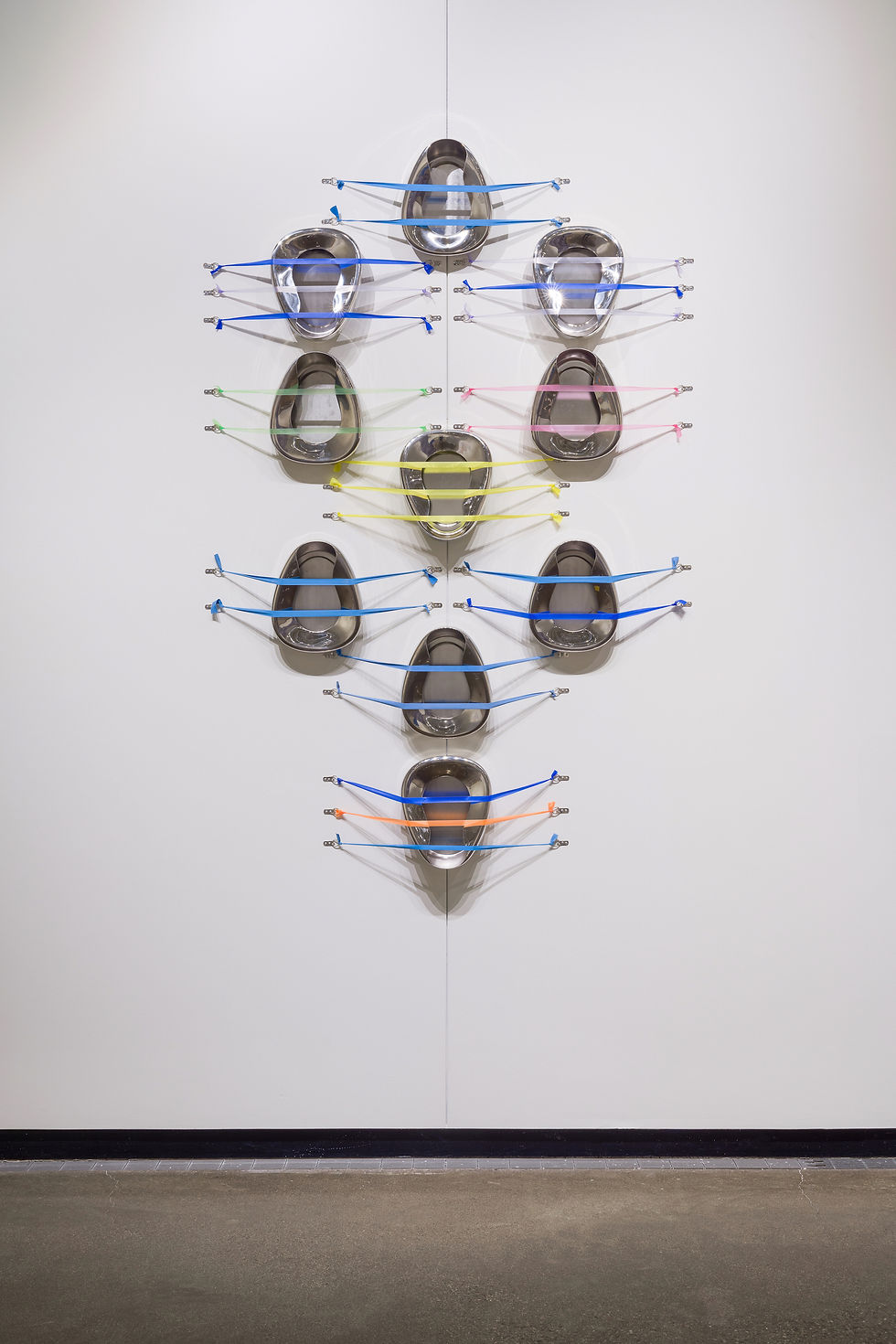

In a podcast interview from July 2025, zegers talked about their scent work as attempting “a collapse of time and space”. These aspirations are evocatively manifested in a 2024 installation at the space Prairie entitled “(d)olor atemporal”, which consisted of a poetic array of sparse but conceptually and sensually potent interventions that suggested a tastefully curated taxonomy of remnants from a future epochal flood. At various spots on the lower area of the walls, short rows of rusty machine screws alternate with visually analogous crinoid shells, accompanied by “destructive distillation of shells, dry distillation of 35-million-year old fossilized resins”, to form a piece called vitrud petrificante. In metanogénesis vítreo, four small organically misshapen, semi-translucent, corroded and encrusted vessels are unevenly spaced on a low shelf, identified as “ancient perfume bottles (ca. 100 AD)” accompanied by “molecular derivatives of petroleum”. The one item on a pedestal, transformación bentónica, is a small rounded shape identified as “seabed stone with fossilized fragments, microplastic accord, ocean debris accord, seaweed accord”. Lastly, the areas flanking the front door are decorated at the level of the floor and the windowsills with neat long piles of white fragments identified as salt and “post-consumer plastics”, comprising the piece temporeidad-extático-horizontal.

In this visually quiet but chemically, historically, and prehistorically charged environment, the perceptual apparatus of the mind is given ample blank space to project complex associations and dreamlike narratives. In its ambiguity of time and scale the exhibition evokes the essay “Constructions in Analysis”, wherein Freud asserts that “(t)he psychoanalyst’s work of construction, or if it is preferred, of reconstruction, resembles to a great extent an archaeologist’s excavation of some dwelling-place that has been destroyed or buried, or of some ancient edifice”. He continues,

(J)ust as the archaeologist builds up the walls of the building from the foundations that have remained standing, determines the number and position of the columns from depressions in the floor and reconstructs the mural decorations and paintings from the remains found in the debris, so does the analyst proceed when he (sic) draws his inferences from the fragments of memories, from the associations and from the behaviour of the subject of the analysis.

While Freud’s primary intent may be to describe the process of therapeutic deduction, bringing the example of a material archaeological site into the space and temporality of an individual’s inner life has the effect of underscoring both the shared and social nature of the unconscious, its objective character, and the ongoing processes of unintentional but nonetheless deliberate erasure that permit a person to feel secure and coherent.

If the unconscious beneath our islands of individuality can be described as a shared underwater convergence of not only a family or a culture, but the accumulated detritus of untold generations of countless species, the multimodal dynamism of aquatic ecosystems can be a meaningful reference point for aesthetic intervention in the social sphere. A compelling and tangible enactment of this idea took place in the Chilean pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2022, which hosted the project Turba Tol Hol-Hol Tol by the collective Ensayos. This multifaceted and transcontinental body of works centered on the vulnerable peatlands of Tierra del Fuego in southern Chile, essential sites of ecological vitality and carbon sequestration, and its title was derived from the language of the Selk’nam people indigenous to that region, members of whom were active participants in the project. zegers contributed to Turba Tol Hol-Hol Tol through collaboratively producing two scents, titled Damp and Rich, intending to both celebrate and defend the bogs and fens of Amenia, New York, verdant with acidic sphagnum moss.

This shared effort to acknowledge abandoned, exploited, and endangered land and people recalls the landmark 1968 project Tucumán Arde, in which artists, organizers, researchers, and workers came together during the height of the US-backed military dictatorship in Argentina to document and describe the plight of communities in the impoverished sugar-producing province of Tucumán. The project was presented twice but was swiftly closed by the authorities at both locations. This state repression resulted in a range of dire consequences for participants and marked a major turning point, with South American conceptual art in the 1970s and 1980s becoming far more cryptic and elliptical, as highlighted in the courageous yet subliminally subtle interventions of figures such as Lotty Rosenfeld and Alfredo Jaar. zegers' father ran an underground press in the latter days of the Pinochet dictatorship, while their mother was a practitioner of mystic spirituality; the ethos in zegers’ work, which they describe in their podcast interview as “a portal into invisible worlds”, can thus be seen as an accord of these tendencies.

For their part, zegers has also been exploring undetectable scents, mining the non-odors of museum HVAC systems in a recent workshop at the Richmond Institute for Contemporary Art. This gesture functioned as a commentary not only on institutions, but on the contemporary minimalism of commercial “clean” scents, framed as they are by value-laden narratives of race, class, sexuality, gender, and ability. This critique extends into the contemporary moment the history Fretwell writes about, in which commercial perfume “was promoted as a chemical essence, a bodiless scent, over and against the ethnological concept of racial odor.” In such a context, a lack of scent can be understood as a sealed enclosure in what zegers identifies as the “depthlessness” of non-porous plastic, reframing the impermeable ideological veneer in every commodity as the collective unconscious of the capitalist death drive.

Comments